Jazz Album Review: Chet Baker Trio’s “Live in Paris”

By Michael Ullman

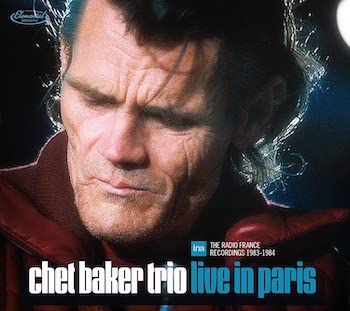

Live in Paris: The Radio France Recordings 1983-1984 is an example of solid, appealing late Chet Baker, doing what he did best with standards and the occasional original.

Chet Baker Trio, Live in Paris: The Radio France Recordings 1983-1984 (Elemental Records)

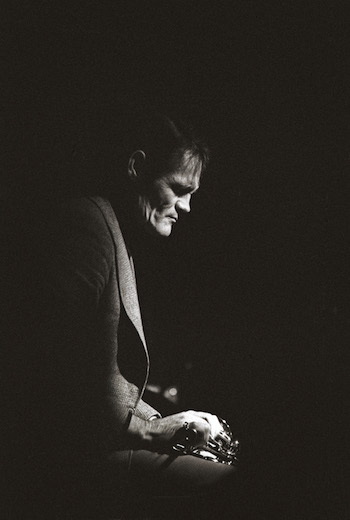

Chet Baker at Lennie’s on the Turnpike in the ’70s. Photo: Michael Ullman.

There’s a scene in the 1988 documentary about Chet Baker, Let’s Get Lost, in which he attempts to cavort on a beach with, as I remember it, at least one beautiful girl. It’s an unconvincing scene. Chet Baker was the least carefree person I’ve ever met. He was an internationally recognized star who seemed to take no pleasure in his successes. In the 1954 down beat poll, while still in his early twenties, Baker was chosen the top trumpeter with 882 votes. (Dizzy Gillespie was second with 661. Louis Armstrong and Miles Davis were far down the list.) Baker was 24: his success was largely based on his hit version of “My Funny Valentine” with the piano-less quartet he co-led with Gerry Mulligan. When I talked to him in the late ’70s, he said he wished he hadn’t been so successful so young. He didn’t deserve the award, he said, and other trumpeters resented his rapid ascension. “Yeah, at 24 (I was) really not ready for it. I’m still not ready for it. I just want to play, that’s all.”

In my experience, the only time Baker was still, or anything like it, was when he was playing music. Then his concentration seemed complete. In the ’70s he was in what felt like his second career. After losing his teeth the previous decade, he had had to remake his technique. Trumpeters might be interested in what he said to me about it: “I put a lot more of my lips into my mouthpiece now, rather than stretching my lips. Strange…You know how a trumpet player will always, when he gets ready to take a breath the mouthpiece remains on the upper lip and the lower jaw drops. Mine is just the opposite. I leave it on my lower lip and take my upper lip off. I have two different embouchures now which I play with…. I still don’t have much range. It’s very difficult to play a high A …I used to press (on the mouthpiece). Now, there is almost no pressure. It’s very difficult.”

It’s lucky that his style never depended on his range, speed, or even volume. His playing is warmly intimate. He seems to be whispering with his minimal vibrato, yet his tone is as rich as anybody’s. He’s thoughtful and yet precise and in tune. He can sound simultaneously super cool and almost innocent in the way he follows his invented melodies. (Miles Davis was intense. Chet Baker intent.) He was a singer before he played trumpet: he said that when he was 11 or 12 his mom used to drag him around to sing at amateur contests. He never won, but he came in second once. My feeling is that his lyricism as a trumpet player may be partially due to his early vocalizing. But in his notes to Baker’s Holiday, the trumpeter’s tribute to Billie Holiday, he says the opposite: “My phrasing as a trumpet player has been influenced a lot by my playing.” Perhaps it goes both ways. He describes his vocal style this way: “The things I’m really conscious of when I sing are intonation, good diction without over-enunciating, a casual, relaxed way of phrasing, and singing in tune.”

Live in Paris, which I have on two CDs (it will also be available as a three LP set), consists of recordings by Radio France made on June 17, 1983 and February 7th, 1984. In both cases Baker is accompanied by pianist Michel Graillier. On the first date, Dominique Lemerle plays bass with the drum-less trio; in the second, Riccardo Del Fra is the bassist. What is striking about Baker’s singing and playing on these sessions, and is slightly different from his early work, is how nimbly he plays with time and phrasing. On “Easy Living,” after a piano introduction, Baker plays the first phrase of the melody — it goes with the lyric “living for you”– then he holds the next note beyond where it should be, pauses in mid phrase and finishes the line as if nothing happened. His theme statement mixes held notes with the occasional staccato single notes, or a deliberately smeared low note. His sound is rich… the recording puts him in a resonant space. On “Easy Living,” he almost seems to stumble down to his lowest range at the beginning of his improvisation, as if to draw attention to the beauty of his bottom notes. On “But Not for Me,” famously recorded by Miles Davis, Baker begins by singing in a burst…I’m not sure anyone could sing “any Russian play” any faster. At points, unlike Billie Holiday, he’s ahead of the beat, though obviously he has to compensate later. He’s avoiding any hint of languor. I like the way he holds the “I” in “I guess she’s not for me, ” then finishes the phrase and arrives at the beat before scatting a chorus.

Live in Paris, which I have on two CDs (it will also be available as a three LP set), consists of recordings by Radio France made on June 17, 1983 and February 7th, 1984. In both cases Baker is accompanied by pianist Michel Graillier. On the first date, Dominique Lemerle plays bass with the drum-less trio; in the second, Riccardo Del Fra is the bassist. What is striking about Baker’s singing and playing on these sessions, and is slightly different from his early work, is how nimbly he plays with time and phrasing. On “Easy Living,” after a piano introduction, Baker plays the first phrase of the melody — it goes with the lyric “living for you”– then he holds the next note beyond where it should be, pauses in mid phrase and finishes the line as if nothing happened. His theme statement mixes held notes with the occasional staccato single notes, or a deliberately smeared low note. His sound is rich… the recording puts him in a resonant space. On “Easy Living,” he almost seems to stumble down to his lowest range at the beginning of his improvisation, as if to draw attention to the beauty of his bottom notes. On “But Not for Me,” famously recorded by Miles Davis, Baker begins by singing in a burst…I’m not sure anyone could sing “any Russian play” any faster. At points, unlike Billie Holiday, he’s ahead of the beat, though obviously he has to compensate later. He’s avoiding any hint of languor. I like the way he holds the “I” in “I guess she’s not for me, ” then finishes the phrase and arrives at the beat before scatting a chorus.

The two sets are recorded differently. In the later date, Baker comes across in the right channel, and the bassist in the middle. They play another Miles Davis-connected tune, “Walkin’” at first as a duet between Baker and bassist Del Fra. It’s a welcome break — the space adds to the drama and the clarity of Baker’s improvisation. If there is a fault in the performance here, it’s the occasional business of pianist Graillier. Baker does not need to be led through the changes of what would have been familiar works.

The longest piece on the set (almost 19 minutes) is “Arbor Way” by Brazilian composer Enrique Pantoya. Baker announces the tune and subsequently his first trumpet phrase is over-miked. Nor is the sound perfect on Horace Silver’s “Strollin.” At the beginning of “Lament,” Baker is too close, too loud, and then after an adjustment, too distant. Of course, that kind of thing is almost inevitable with live performances, but I am happy to report that the sound of Baker’s trumpet and singing are for the most part captured accurately and pleasingly. Radio France knew what it was doing. Live in Paris offers intriguingly distinctive instrumentation: it is also an example of solid, appealing late Chet Baker, doing what he did best with standards and the occasional original.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.