Book Review: “How I Survived a Chinese ‘Reeducation’ Camp” — A Desperately Needed View of China

By Maxwell Olin Massa

It is invaluable for the world to have an in-depth account from someone who passed through the Xinjiang re-education system and was brave enough to tell the tale.

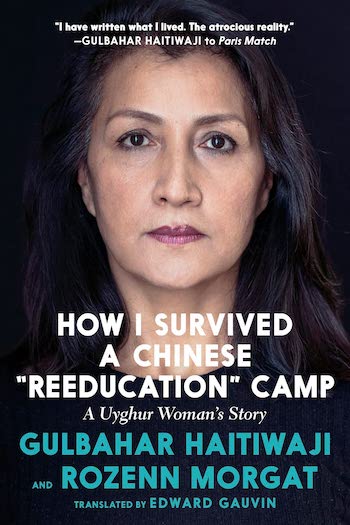

How I Survived a Chinese “Reeducation” Camp: A Uyghur Woman’s Story by Gulbahar Haitiwaj with Rozenn Morgat. Translated by Edward Gauvin. Seven Stories Press, 240 pages, $26.95.

How I Survived a Chinese “Reeducation” Camp: A Uyghur Woman’s Story was a desperately needed memoir: it is the first accessible, authentic account of what life is like in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s secretive prison apparatus dedicated to doctrinal reprogramming and oppression. It is invaluable for the world to have an in-depth account from someone who passed through the Xinjiang re-education system and was brave enough to tell the tale. But, while this volume is a cause for celebration, there are limitations in how it was executed, and it is useful to point these out.

How I Survived a Chinese “Reeducation” Camp: A Uyghur Woman’s Story was a desperately needed memoir: it is the first accessible, authentic account of what life is like in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)’s secretive prison apparatus dedicated to doctrinal reprogramming and oppression. It is invaluable for the world to have an in-depth account from someone who passed through the Xinjiang re-education system and was brave enough to tell the tale. But, while this volume is a cause for celebration, there are limitations in how it was executed, and it is useful to point these out.

Rozenn Morgat tells the story of how one Uyghur woman, Gulbahar Haitiwaji, was tricked into returning to Xinjiang from her expatriate home in France. She was then imprisoned for two and a half years in a series of Chinese “reeducation” facilities on a trumped-up charge of assisting a Uyghur separatist movement. The narrative opens with a description of Haitiwaji’s life in Xinjiang’s Karamay, back in the ‘90s, where she worked as an engineer at a petrochemical company (sadly, Karamay’s history with the CCP was already troubled: a 1994 theater fire ended with 288 schoolchildren obediently burning to death while senior Party functionaries filed out first). After being passed over for promotion in 2002, her husband left for France and claimed asylum. She ultimately followed him. Later on, in 2016, she was summoned back to Xinjiang, supposedly to deal with “formalities” regarding her pension. She was detained shortly after her arrival for suspected involvement in the World Uyghur Congress, which the Chinese government recognizes as a terrorist group. She was quickly taken into a detention center and eventually transferred to the reeducation system. In the end, the French government intervened and freed her. When Haitiwaji returned home she decided to tell her story.

The book is at its best when Haitiwaji details her experiences. These passages are evocative and immersive. For example, the opening descriptions of life in Karamay provide a wonderful introduction to a part of China that is not widely known but highly interesting. Other, smaller moments are very poignant, such as the sequence when Gulbahar is given her clothing back when she is released from jail and moves into the reeducation center in Baijiantan (白碱滩). Similarly, the description of her final round of interrogation makes for forceful drama. But there are long stretches here in which not much happens. For the most part, life in a reeducation center resembles Flann O’Brien’s characterization of Hell in The Third Policeman: cyclical regularity. Day in and day out is pretty much the same. So we end up with passages like this, descriptive of changes in her way of life after Xi Jinping’s “reelection” in 2017:

The first thing they did was ban all free time. Weekends did not exist here. We worked all week from sunrise to sunset. Each day was exactly like the last. And while it had been that way for months, Saturday and Sundays had always stood out – although they’d had their share of chores and classes, on those nights, the guards might let us out of our cells for a few hours, depending on their mood…

Is this a couple weeks? A month or two? A year? It’s hard to say. It is frustratingly nebulous. Why didn’t Morgat include details about the French maneuvering to bring Haitiwaji back? That would have added a much needed element of suspense. And the story would have had the added value of exploring how governments react to requests for assistance from people who have been imprisoned unfairly by authoritarian powers.

Gulbahar Haitiwaj. Photo: Seven Stories Press

On top of that, questions are raised when one person relates the experience of another. An engineer by training, Haitiwaji sounds like a rather down to earth person. Morgat is a reporter who, it seems to me, wants to heighten the real life drama. So there is a tension between the voices. Sometimes these inconsistencies are small. Morgat asserts in the preface that the CCP only arrived in Xinjiang in 1955, but a few pages later Haitiwaji suggests that they arrived in the province in 1949. At one point Haitiwaji confesses that she “wasn’t the best student,” but she managed to get by. Later she asserts she had “always been a model student.” Given the value of this testimony, the disconnects are bothersome. It is probably safe to assume that the more activist statements reflect the sensibility of the reporter; the more accepting and unassuming reactions come from the engineer. This friction never rises to the point of compromising the narrative, but it casts doubt on the sections of internal monologue, particularly Gulbahar’s more politicized musings.

Finally, the book doesn’t do an effective job of distinguishing the mistreatment distinctly reserved for the Uyghurs from the routine exercise of political oppression that defines life in China. Haitiwaji’s trial was an utter mockery of justice, but it also resembled – very strongly – what ordinary Chinese trials look like. Justice is a sham for everyone in China: the country’s conviction rate is currently over 99.9%. The chance of acquittal has rarely drifted much above one in a hundred since 1970. When I was studying Chinese criminal law at Nanjing University, a professor pointed out that the statistically detectable benefit of retaining a defense lawyer approaches zero: legal representation is worthless across the system. Recognizing this fact would have strengthened the book’s authority without in any way diminishing the suffering of the protagonist.

Despite its flaws, How I Survived a Chinese “Reeducation” Camp is an indispensable document. It shares the strengths and weaknesses of the short 2021 Oscar-nominated documentary Do Not Split. Like that provocative movie’s treatment of the Hong Kong riots, the book serves as a timely and compelling introduction to a terrifying form of human cruelty. Let’s hope that it succeeds in raising awareness. The nuances of China’s barbarity will no doubt be revealed in the future.

Maxwell Olin Massa is a graduate of the Hopkins-Nanjing Center and currently works as a policy analyst in the DC area. In addition to having written on the rule of law, he is also a staff writer for Third Factor magazine and published House of Apollo, a novel of ideas, with Whiskey Tit Books in 2020. He was even a Chinese TV host for a year, once upon a time.

Tagged: Edward Gauvin, Gulbahar Haitiwaj, How I Survived a Chinese “Reeducation” Camp