Arts Remembrance: Homage to Gilbert Gottfried — One of America’s Most Original Stand-ups

By Betsy Sherman

Comedian Gilbert Gottfried’s passing has hit me harder than most deaths of my celebrity faves: it’s a deprivation I can feel in my stomach.

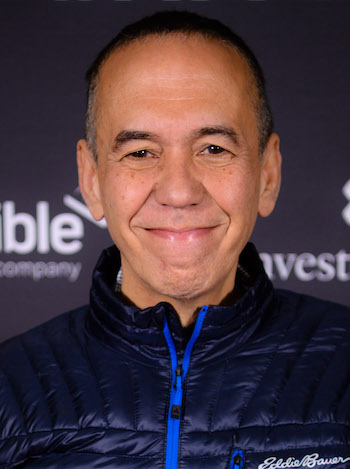

Gilbert Gottfried — the ultimate roast comic. Photo: Wikidpedia

It’s not fair that Gilbert Gottfried, who had been the embodiment of a little old man for most if not all of his existence, hardly got to be one in real life. He succumbed to illness earlier this month at age 67. That stilled the heartbeat, and shut the mouth, of one of the nation’s most original stand-ups, one whose hilariously abrasive, bellowing voice was recognizable even to those who knew nothing about his act (America’s favorite pushy New York Jew!).

After years of being a comedian’s comedian, fearless in front of a microphone, Gottfried won family-friendly fame as the voice of Iago, the villain’s parrot, in Disney’s 1992 Aladdin. Thereafter, in addition to being a favorite on Letterman, Conan, and Howard Stern, Gottfried was in demand on mainstream shows such as The View, and was a regular on the rebooted Hollywood Squares. This doesn’t mean Gottfried was tamed — once producers lit the fuse, they and the audiences often got something more explosive than expected.

Gilbert’s passing has hit me harder than most deaths of my celebrity faves: it’s a deprivation I can feel in my stomach. That’s because a significant part of my past eight years has been spent listening to Gilbert Gottfried’s Amazing Colossal Podcast, a transportingly pleasurable experience, especially during the pandemic. GGACP made possible a whole new level of Gilbert fandom. Across 400+ episodes, the famously opaque performer (on stage he’d keep his eyes closed and sometimes his back to the audience) has actually revealed bits of himself. This isn’t through a Marc Maron-esque confessional style, but through discussions of his tastes in pop culture.

More about the pod later; first, let’s go back to the beginning. Born in 1955 in Brooklyn to a family with no ties to show business, Gottfried started doing standup at 15 and never looked back, working his way from the New York City clubs to a national circuit that would boom in the ’80s.

Watching Gottfried’s 30- or 40-year-old standup shows is like seeing some ancient Borscht Belt denizen emerge from the small-framed comic, squinting and protesting against a world of mullets, Members Only jackets, and coke spoons. Except the vaguely Yiddish-inflected old-timer doesn’t get to do his familiar set-up/punchline, set-up/punchline: he does a strange, surreal mutation where the set-up is rolled around for several minutes and, often, the punchline never does arrive. There were impressions in the act too, but coming from absurd angles, such as Bob Dylan and The Andy Griffith Show’s Floyd the Barber conversing in their respective constipated whines. Gottfried carried the anti-comedy comedy torch of Andy Kaufman, Steve Martin, and Albert Brooks.

One constant in Gottfried’s work was the lampooning of phony sentimentality. He never ranted about it directly, but the intention was clear. For example, while winding down a show, he’d slip into the end-of-telethon mode of Jerry Lewis, begin gravely intoning “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” and upend a water bottle over his eyes to simulate the requisite stream of tears.

He was the ultimate roast comic, reveling in bad taste and quick with razor-sharp insults (beyond the roasts, there’s the filthy fun of his Dirty Jokes DVD and The Aristocrats). The incidents that made headlines were his making jokes at the Emmys about Paul Reubens’ bust for masturbating at a Florida porno theater; his proverbially “too soon” joke about September 11th; and his tweet about the tsunami in Japan that got him fired from his gig as the voice of the duck in Aflac insurance commercials.

Gilbert Gottfried’s Amazing Colossal Podcast was inspired by the scenes in Woody Allen’s Broadway Danny Rose in which comics sat around a deli table telling stories about showbiz characters, major and minor. GGACP features — humor me, I will continue to use the present tense — lovingly surgical examinations of pop culture debris. The pod has a slew of catchphrases, many involving alleged perversions of old-timey stars including Cesar Romero, Danny Thomas, and Alan Ladd.

Seeing how Gottfried is, let’s say, social-skill impaired, he’s Sherpa-ed in the hosting duties by comedy writer/producer Frank Santopadre, a fellow obsessive. Gilbert’s inexplicable memory for trashy theme songs for TV shows and movies is a delight: he’ll sing them off-key and off-tempo and eventually dissolve into laughter.

The show’s particular mitzvah has been conversations with nonagenarians. It’s lovely when the hosts get fresh nuggets out of oft-interviewed stars such as Carl Reiner and Dick Van Dyke. But it’s astonishing to be bowled over by figures you may never have heard of: two of the most memorable episodes were with children’s TV host Sonny Fox and Mad magazine writer Al Jaffe, both of whom shared moving personal stories from their pre-career lives.

For an even deeper dive into the enigma that was Gilbert Gottfried, there’s the wonderful 2017 documentary Gilbert, directed by Neil Berkeley. In it, we meet his young children, Max and Lily, and an important force in both his life and career, his wife Dara (producer of GGACP). And we meet the shy, soft-spoken, off-stage Gottfried — for all his eccentricities, a nice guy.

Prominent in the podcast and the documentary is Gottfried’s love for not only the monster movie genre, but also for the monster characters in those movies. Among his perceptive theories is that Boris Karloff’s powerful performance as Frankenstein’s Monster came from the actor’s understanding that the monster was an oversized kid who’s discovering the world. Gottfried had a similar special regard for Lon Chaney Jr.’s performance as Lenny in the 1939 Of Mice and Men.

Listen to GGACP wherever you get your podcasts. You could perversely start with the two-part In Memoriam 2021 shows. This annual tradition of affectionately toasting those who have passed will give you a sense of the hosts’ senses of humor, and their values. They feel these losses profoundly.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for the Boston Globe, Boston Phoenix, and Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.

Great article you captured Gilbert to a tee

Betsy, thank you for the lovely article and tribute. So glad the show had meaning for you and entertained you.

Frank Santopadre