Arts Commentary: Containing Multitudes — Five Shows Explore the Intersections of Identity and Performance

By Tim Jackson

In dealing with the turmoil of ‘real’ life, the art of illusion found in cinemas, theaters, and museums will help us regain a sense of who we are as communal beings.

In 1959, Erving Goffman published The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, a seminal book on self-performance in public and professional life. I first encountered his book in an acting workshop, where his ideas were used to provide clues into observing human behavior. Goffman claimed that in the real world people present themselves in ways that will “pass a strict test of aptness, fitness, propriety and decorum.” Today, that is far from the standard encouraged by social media stages such as YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Reality TV, or dating and hook-up apps. Social skills have now become highly performative. The Covid pandemic compounded that development — screens were a necessity. We gather ‘ face to face’ through Zoom, Marco Polo, and other apps, arranging agreeable backgrounds behind us, selecting walls of suitable books or faux tropical backgrounds. But the move away from decorum has led to an increase in unhealthy psychological and social outcomes: depression, panic attacks, and social anxiety. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, approximately 10 percent of young adults and adolescents in the United States have “an intense fear of being watched and judged by others.”

In 1959, Erving Goffman published The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life, a seminal book on self-performance in public and professional life. I first encountered his book in an acting workshop, where his ideas were used to provide clues into observing human behavior. Goffman claimed that in the real world people present themselves in ways that will “pass a strict test of aptness, fitness, propriety and decorum.” Today, that is far from the standard encouraged by social media stages such as YouTube, Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, Reality TV, or dating and hook-up apps. Social skills have now become highly performative. The Covid pandemic compounded that development — screens were a necessity. We gather ‘ face to face’ through Zoom, Marco Polo, and other apps, arranging agreeable backgrounds behind us, selecting walls of suitable books or faux tropical backgrounds. But the move away from decorum has led to an increase in unhealthy psychological and social outcomes: depression, panic attacks, and social anxiety. According to the National Institute of Mental Health, approximately 10 percent of young adults and adolescents in the United States have “an intense fear of being watched and judged by others.”

Can the arts help us regain a sense of proportion and harmony? Will writers and visual artists be able to offer fresh perspectives on how social performance is shaped by language, gender, race, nationality, economics, and cultural heritage? The answer is yes. I took in a number of recent artworks that probed the increasingly ambiguous line between the performed and authentic self: the plays People, Places, and Things and English, the film documentaries El Father Plays Himself and Procession, and the exhibit Gillian Wearing: Wearing Masks at NYC’s Guggenheim Museum.

In Duncan Macmillan’s People, Places and Things (recently closed at the Speakeasy Stage), a drug-addicted actress at a rehab facility stubbornly refuses to confront her ‘real’ self. Lost in the various identities she puts on, Emma (Marianna Bassham), whose real name turns out to be Sara, resists participation in role-playing group therapy. She refuses to expose her life to strangers because she is more comfortable assuming roles or escaping into a haze of drugs and liquor. Macmillan’s drama questions whether she can be transformed or even rehabilitated. Ostensibly, the subject is addiction, but acting itself is also critiqued, seens as a means of eluding reality. As the play opens, we see Emma falling apart in a production of The Seagull. Like Madame Arkadina in Chekhov’s masterpiece, Emma is vain and a bit delusional. Chekhov poses a number of discomforting questions about why actors act. Do they perform for the sake of artistic fulfillment — or is it all about garnering fame and attention?

Marianna Bassham in People, Places and Things. Photo: Nile Scott Studios.

The play’s title draws on the psychological intersections between actors and addicts. Alcoholics Anonymous classifies “people, places, and things” as triggers to avoid while, for the actor, they are creative tools. An actor must develop a relationship with other characters in a production as well become comfortable with the set and props. This contrast is a cruel irony for Emma; she uses acting, its layering of identities through role-playing, to shield herself from unrelieved pain. Dropping her masks in order to submit to the judgment of a group of strangers is unacceptable. Yet everyone in the group of addicts faces trauma by dropping their dedication to illusions about themselves and confronting reality.

Emma/Sara is not a sympathetic character. Audience members are asked to come to their own conclusions and make their own judgments. The final scene steps in a Pirandellian direction: the play’s cast members enter as actors waiting for an audition. Each one carries their head shot and stands; they mumble and try out their lines. Sara reads first, script in hand. In this dialogue, she is finally candid about fate and trauma, life and illusion.

A scene from El Father Plays Himself.

El Father Plays Himself, which screened recently at Boston’s Docyard series, looks at role-playing and drama therapy with a distinctive twist. In this observational documentary, Mo Scarpelli followed her partner, Venezuelan filmmaker Jorge Thielen Armand, into the jungle of Venezuela, where he was directing a film called La Fortaleza. The story centers on the father’s attempt to overcome his alcoholism by going off to work in an illegal gold mine controlled by Colombian guerrillas. When Armand cast his estranged father in the title role, Scarpelli seized on the opportunity to film the father-son relationship. Armand left Venezuela for Canada when he was young — partly in order to escape his father — so this daunting jungle shoot was partly about grappling with the past. Viewing short home movies from his childhood reminds Armand of how things once were. During the filming, resentments between the two, seething beneath the surface, are interlaced with tender moments. Still an incorrigible drinker, El Father has fits of temper that threaten to derail his son’s film. “I’m not a whore; I quit,” he bellows at one point after consuming a bottle of rum. “You have to pay for my biography because it’s my history, my life, dumb ass.”

It is a unique dynamic: a son directing his father in a story about the issues that continue to keep them estranged. Meanwhile, Scarpelli’s camera hovers nearby. Armand’s motivation is puzzling: it seems to be an elaborate way of confronting the past that depends on role-playing, an approach reminiscent of the conflicts in Macmillan’s play. El Father is undoubtedly a compelling subject, with his grizzled beard, interrogating gaze, and uncertain temper. In a particularly pivotal scene, the son decides to let the father fuel himself with drink. Is this revenge or creative necessity? Are we watching the making of a film or a psychodrama? Scarpelli’s camera focuses on Armand as he watches the monitor, worried and grim. Finally, the scene wraps — the performance has been surprisingly powerful and honest. El Father, emotionally spent and thoroughly inebriated, screams: “Listen to me, limp dick. I’ll get you an Oscar, you dumb fucker. I’m here kid, all for your fucking film… I miss you so much. You’re a piece of shit, faggot.”

A scene from Procession

The slippery ambiguities of performance is the focus of the documentary Procession. Working with director Robert Greene and a professional drama therapist, six middle-aged men, all childhood victims of sexual assault by Catholic priests, created six individual short films in which they role-played the circumstances of their abuse. Greene has explored this hybrid of acting and actuality before with remarkable results in films such as Actress, Bisbee 17, and Kate Plays Christine. For Procession, it took three years to work through the difficult process of filming, carefully avoiding sensationalism or exploitation. The resulting doc is sad, frustrating, and utterly fascinating. The short films are profound, and the effect they have on the survivors’ lives is liberating and honest.

Language is another way in which we conform (or not) to society’s rules. We tend tojudge people by the words they use and how well they articulate their thought. Because English has become the world’s lingua franca, a requirement for middle-class ambition, tremendous pressure is being placed on native languages around the world. Sanaz Toossi’s play, English, examines the tensions that arise when language, culture, and identity clash: what is gained and what is lost? This Atlantic Theater Company production is set in a classroom where, over of period of six weeks, five students study for the TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) exam. This is an immersive English Only class: it is an infraction for any of the students to speak their native tongue of Farsi. Five infractions and the pupil is dismissed for the day. To create the illusion of two languages, the actors talk in rapid colloquial English when they are “speaking” Farsi lines. Attempting English, they speak with the heavy accents that we might actually hear from a non-native speaker. The students are self-consciousness and vulnerable: sounding like Borat is an embarrassment.

The script gives us five personalities, each struggling with a different relationship between language and identity. One student is desperate to pass an interview, another to emigrate, a third to qualify for a job even though she despises English. The teacher is passionate, committed to seeing this class learn to speak and think in English; she is also determined to maintain her native Iranian identity as she does it. One reviewer neatly summed up English as “an exploration of cultural assimilation and the residual effects of colonialism.” I would argue that the script is also a powerful look at how speech shapes what we perceive to be our public face.

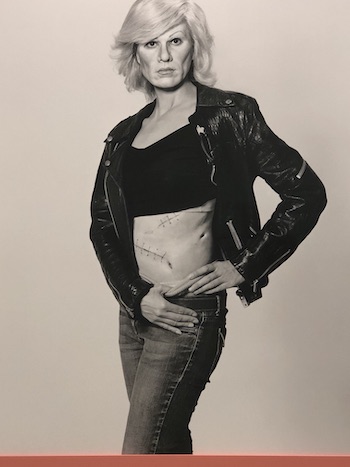

Gillian Wearing’s portrait of Andy Warhol. Photo: Tim Jackson.

Gillian Wearing: Wearing Masks is currently showing at the Guggenheim in New York. The artist uses masks, performance, sculpture, and photography to critique ideas of self-representation. She is one of the key artists of the early ’90s who drew on the aesthetics of mass media to explore transformations in interpersonal relationships as well as the gap between illusion and reality. Here Wearning has printed large-scale photos that, at first glance, are exact reproductions of iconic self-portraits. But look more closely. Wearing’s eyes are staring out of what seem to be perfectly created images of of Robert Mapplethorpe, Claude Cahun and Diane Arbus, and others. For me, the point is that pictures are inevitably representations, a construction that reflects those who created them and those who are looking at them.

Wearing’s art anticipates the breakdown of public and private that has grown more profound with the rise of social media. The piece called Signs that Say What You Want Them To Say and Not Signs that Say What Someone Else Wants You To Say is comprised of fifty individual portraits from the streets of London. Each participant holds a sign in which there is a short candid message: “I like to be in the country” or “I signed on and they would not give me nothing.” One well-dressed young man smiling hesitantly holds a sign reading “I’m desperate.”

In Fear and Loathing, the artist’s latest “confessional booth installation,” Wearing had made short videos featuring ordinary people from Los Angeles, their identities protected by high-quality latex masks. They tell stories about police brutality, sexual assault, their fears of success and failure. In 2 into 1, a British working-class mother and her teenage twin boys discuss their family and frustrations. But vocal roles are reversed: the mother is lip-syncing the children’s voices while the children are lip-syncing their mother’s words (sections of this video are available on YouTube). The effect of these and other Wearing pieces is to blur fact and fiction; we don’t really know if the stories are true or whether the masks encourage performance. Wearing is also out to highlight the disconnect between physical presence and captured image, between inner life and public persona.

The artists I have considered take up the theatrical presentation of everyday life, exploring when our behaviors can be taken as arbitrary, intentional, genuine, or a facade. In a post-pandemic world, given the ubiquity of social media, what will it be like to move back into public spaces with others? Will we feel differently as we gather together? Art will no doubt aid us in coping with these challenges by helping us to appreciate differences, to recognize that everyone has their way of confronting war, disease, social and political divisions. In dealing with the turmoil of ‘real’ life, the art of illusion found in cinemas, theaters, and museums will help us regain a sense of who we are as communal beings.

Tim Jackson was an assistant professor of Digital Film and Video for 20 years. His music career in Boston began in the 1970s and includes some 20 groups, recordings, national and international tours, and contributions to film soundtracks. He studied theater and English as an undergraduate, and has also worked helter skelter as an actor and member of SAG and AFTRA since the 1980s. He has directed three feature documentaries: Chaos and Order: Making American Theater about the American Repertory Theater; Radical Jesters, which profiles the practices of 11 interventionist artists and agit-prop performance groups; When Things Go Wrong: The Robin Lane Story, and the short film The American Gurner. He is a member of the Boston Society of Film Critics. You can read more of his work on his blog.