Book Review: “Theatrum Mundi: Masks and Masquerades in Mexico and the Andes” — Utterly 21st Century

By John Bell

In this deeply enlightening study, Anthony Alan Shelton aims to set the record straight about how mask culture developed in Mexico as well as in Andean cultures.

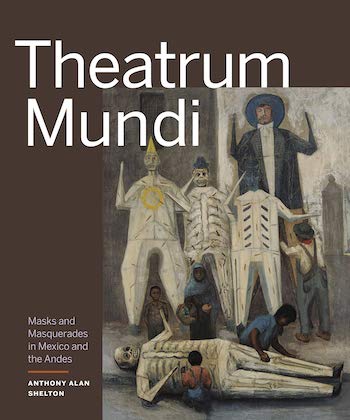

Theatrum Mundi: Masks and Masquerades in Mexico and the Andes by Anthony Alan Shelton. Vancouver: Figure 1, 256 pages, $50.

For puppeteers and puppet historians, masks and puppets seem to be everywhere and nowhere. Those on the lookout for contemporary examples of these forms see them often: as sports mascots, in music videos, political demonstrations, opera and theater productions, as well as street performances, not to mention in the burgeoning world of puppetry. But critics who pay proper attention are few. Masks and puppets are visually striking and they frequently show up on newspaper front pages or on the homepage of a media outlet. Yet there are few attempts to make sense of their function and/or value in the larger culture. Instead, a kind of stupefied awe is the default reaction: “Wow, look at this amazing visual! Wherever did that come from?”

Aside from reacting with wide-eyed wonder, modern culture has not been kind to masks. Beginning in the 16th century, belief in the scientific method, the rise of secular thought, and the growing domination (especially in the theater) of realism turned puppets into suspicious holdovers from primitive (or Catholic) cultural systems. The invention of anthropology and race theories in the 19th century further sidelined masks (especially those from Asian, African, and Native American cultures). They were cast as the last remnants of primordial times, soon to vanish with the triumph of contemporary sensibilities.

In the late ’30s, Minneapolis puppeteer Donald Cordry, after stints building and performing marionettes, first with Rufus and Margo Rose, and then with Tony Sarg, left the US with his wife Dorothy for Mexico, where he spent the rest of his life. Cordry became fascinated by the rich world of Mexican mask performance; he collected and commissioned scores of masks from Mexican mask-makers. He began to write a book about them, which Dorothy had to finish after he died in 1978. Mexican Masks was published in 1980, and the volume became a landmark source on the subject.

But Cordry’s approach was problematic. A good modernist, he envisioned Mexican mask culture as anachronistic, symptomatic of the timeless tradition of pre-Conquest Indigenous culture. Anthony Alan Shelton, in his new study Theatrum Mundi: Masks and Masquerades in Mexico and the Andes, calls this approach “romantic anthropology,” and criticizes the way perspectives of this type miss the important ways that mask performance throughout the Americas remains a vibrant element in contemporary culture, fully engaged with mass media, marketing, and global capitalism. Cordry and others, in their zeal to see the non-European world of masks as ageless, commissioned or collected masks made by prolific Mexican carvers who felt they had to cater to what Shelton calls “archaism, fantasy and nostalgia.” A number of the masks that Cordry collected and wrote about represented newly fabricated designs that were expressly created to satisfy his desire for the exotic. There was no connection to past or contemporary mask dances.

Shelton is as at least as obsessed with masks as Cordry was, but Theatrum Mundi aims to set the record straight about how mask culture developed in Mexico as well as in Andean cultures. It is a complicated story, one that requires diving deeply into the cosmology, history, and culture of Indigenous belief systems. It also calls for understanding the major artists in the field and exercising a command of European cultural and political history, including the nature of Spanish Baroque aesthetics and their influence in the Americas. Finally, there must be an appreciation of the nuanced ways Indigenous resistance to European colonial forces was depicted through the evolution of masked dance and combat dramas.

Butterfly mask from Guerrero, Mexico, designed to evoke archaism and fantasy, from Theatrum Mundi.

Theatrum Mundi reflects the author’s years of devotion to studying what is necessary to do justice to his complex topic. He has met these multidisciplinary demands, and the results are deeply enlightening. In the course of reading the book one becomes familiar with the cosmology of Mexica people, from the Olmec civilization to the present, the city-state of Teotihuacán, and the panoply of Mexica gods from Huitzilopochtli to Tlaloc, including Quetzalcoatl, Tlaltecuhtli, and Chalchiuhtlicue. The importance of medieval and renaissance religious dance dramas in Spain and western Europe is underlined, as well as how this theater of masks, which focused on the conflict between Christianity and Islam, was imposed upon the Indigenous peoples of Nueva España, who already had their own rich culture of “militant, mystic theology” — as Shelton describes it — expressed through the design and performance of masked dances.

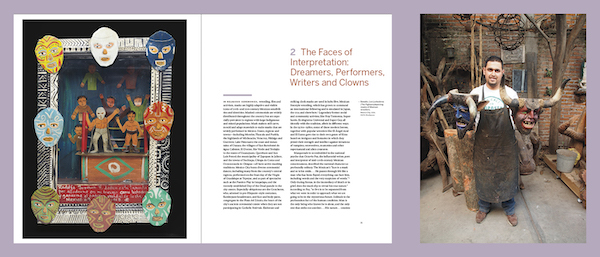

Shelton scrupulously respects the lives of the people who created innovative mask culture in Mexico and the Andes. His book details the history of individual mask makers as well as the background of some mask-making dynasties, such as the Blanco family of Iguala, Mexico. He conscientiously credits “Indigenous ritual specialists” and “traditional knowledge holders” in the same way he lists scholarly sources from the Americas and Europe. He engages fully with the spiritual worlds and nonmodern concepts that continue to be a major part of mask performance. Shelton notes, for example, that Indigenous peoples in the 16th century considered paintings of saints “not as representations but as the saints themselves.” Shelton often refers to the power that emanates from the material world as “numen”: the spiritual force “often identified with a natural object, phenomenon, or place” (according to Oxford Languages).

Shelton’s range of concerns is vast. He devotes two chapters to the nature and meaning of materials used in mask-making, especially turquoise in Mexican masks. He explores how luminescence — the reflective powers of stones, metals, and colors — is part of the enduring symbology of complex cosmologies. He delves deeply into the supply-and-demand details of global mask markets, and the long history (and politics) of mask collecting in museums across Europe and the Americas. Sometimes Shelton’s voluminous expertise intimidates to the point that it overwhelms. Especially when he goes down a specific rabbit hole, whether it is European “Medieval Military Cosmology” and the biography of the anti-Muslim Catholic military hero Saint James (Santiago), or the dynamics of church and state conflicts in the Spanish Baroque period. These examinations often seem to be detours from masks and mask performance per se. Still, it becomes clear that a familiarity with these contexts is essential if we are to go beyond “romantic anthropology” with its fetishization of non-European traditions as quaint, timeless, and distant.

Shelton’s account of a 1539 performance of The Conquest of Jerusalem in Tlaxcala, Mexico, on the feast of Corpus Christi goes beyond the instructive. His examination of the details of the staging are fascinating. Corpus Christi festivals, promulgated by Pope Urban IV in 1264, have long been considered the impetus for centuries of medieval and Renaissance display and street performance in Europe — often with puppets and masks. Their imposition on Mexican communities, as part of the suppression of Indigenous belief systems and the conversion of whole populations to Christianity, was central to the Spanish colonial powers implementing their political and religious goals of subjugation.

Sheldon argues that the 1539 Conquest of Jerusalem represented the complicated meeting of two disparate cultures: Spanish and Mexican. Both communities were deeply engaged in creating a performance practice that dramatized multiple belief systems by mixing-and-matching cosmologies, aesthetics, and politics. Orchestrated “by the city’s Indigenous elite” and “scripted, sung, and performed” in the Nahuatl language, the performance “explicitly expressed aspects of an Indigenous world view by recounting Tlaxcalan alliances with the Spanish against the Mexica.” The Conquest of Jerusalem affirmed the “special privileges and relationship” that the conquistador Hernán Cortés had granted the Tlaxcalans.

The Tlaxcalans turned the center of their city into a gigantic outdoor performance space, and Shelton lovingly details this fabulous, time-bending spectacle. Ostensibly based on the actual taking of Jerusalem from the Fatimid Caliphate by European Crusaders in 1099, the epic theater production featured Tlaxcalans performing as the European forces as well as “the magnificently attired army of Nueva España, including Tlaxcalans, Mexicas, Huastecs, Cempoalans, Mixtecs, Acolhuacans, Purépechas, Caribs, and Guatemalans,” all fighting on the Christian side to defeat “an army of Moors and Jewish people,” also played by Tlaxcalans. Over the course of three extensive battles, the fortunes of the armies go back and forth. When it looks as if the Moors will triumph, the Pope sends Santiago to command the Hispanic forces and San Hipólito, the protector of Indigenous people, to lead the army of Nueva España, for a collective ultimate victory.

At the close of the play, the Indigenous performers portraying Moors were baptized on the spot. This mind-boggling overlay of European Christian/Muslim conflict on top of the politics of the Spanish conquest played out on a number of levels, including a local nod to the dominant Franciscan order’s conflicts with competing religious orders in the New World. This extravaganza would seem to serve as an exciting, interactive colonialist pageant that celebrated the people of Tlaxcala. But Shelton points out that, during the same period, nearby Indigenous ceremonies “dedicated to the maize goddess, Chicomecóatl” sparked such punishments as heresy trials. In other words, despite the collaborative production of mask dramas (the product of what Shelton calls the “colonial theatre-state” of New Spain), the Indigenous and Spanish colonial worlds were “irreconcilably divided.” Over the centuries, however, as mask performance practices continued to develop, Indigenous perspectives persisted and thrived.

Shelton’s path through multiple strands of Mexican and Andean mask performance history is convoluted, but his investigations are well worth pursuing. Over 40 years ago, Donald Cordry appreciated the importance of the Mexican masks he documented, but didn’t fully recognize the intricacies of their convoluted history and how this past lived on in the present. Shelton does, and proves in Theatrum Mundi that ancient Mexican and Andean mask culture is also utterly 21st century

Puppeteer and theater historian John Bell is the director of the Ballard Institute and Museum of Puppetry and an associate professor of Dramatic Arts, both at the University of Connecticut. He learned puppetry as a member of the Bread and Puppet Theater company from 1976 to 1986, and received his doctoral degree in theater history from Columbia University. He is the author of many books and articles about puppet theater, and is an editor of Puppetry International. John is a founding member of the Brooklyn-based theater collective Great Small Works; one of the creators of the Honk! Festival of Activist Street Bands; and a member of the Second Line Social Aid and Pleasure Society Brass Band.