Theater Interview: Tennessee Williams and Censorship

By Robert Israel

“A lot of censorship in America has to do with the impulse to shut down what women have to say, literally hanging and burning them as witches to shut them up.”

For its 16th season on September 23-26, the Provincetown Tennessee Williams Theater Festival continues to stage plays and rediscovered scripts-in-process by one-time Provincetown summer resident Tennessee Williams, as well as by other playwrights aligned with or influenced by his work. In previous years, regional performers have been joined by national and international thespians traveling to the Outer Cape from Texas, New York, New Orleans, South Africa, China, and Europe. This year, due to the international pandemic, the artists will all be American. In compliance with Covid guidelines, most of the events will be held at outdoor sites or tented venues with open sides. There will be live performances, mixers, films, parties, and music. The theme — initially planned for 2020 — is Tennessee Williams and Censorship.

Arts Fuse interviewed David Kaplan, Festival curator, and asked him about this year’s theme, why it was chosen, and what audiences might expect.

Arts Fuse: What’s the connection between Tennessee Williams and censorship?

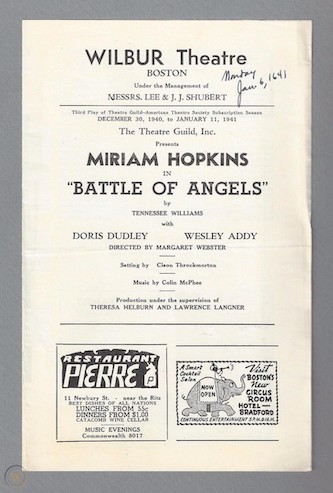

David Kaplan: Throughout his career, Williams couldn’t catch a break. Censors hounded him everywhere he went, beginning in Boston in 1940. He’d written a play, Battle of Angels, that was meant to be his first Broadway production. The Boston City Council excoriated his writing. It wasn’t quite “Banned in Boston,” but councilman called it “putrid” and the city fathers demanded that cuts be made to the script. So, right from the beginning his work was set upon and Williams was maligned.

David Kaplan: Throughout his career, Williams couldn’t catch a break. Censors hounded him everywhere he went, beginning in Boston in 1940. He’d written a play, Battle of Angels, that was meant to be his first Broadway production. The Boston City Council excoriated his writing. It wasn’t quite “Banned in Boston,” but councilman called it “putrid” and the city fathers demanded that cuts be made to the script. So, right from the beginning his work was set upon and Williams was maligned.

This continued in Hollywood with film adaptations of his work — Baby Doll, A Streetcar Named Desire, and the Rose Tattoo — where cuts in the script or in what had been shot were insisted upon by censors, who, interestingly enough, did not so much object to homosexual depiction in his work, but to depiction of a woman’s sexual desire for a man.

For example, what censors objected to (and cut from the film behind Williams’s back) were the reaction shots when Kim Hunter, playing Stella, looks at Marlon Brando, playing Stanley Kowalski, with unembarrassed lust.

Fast forward to the “new critics” in the New York Times, New Republic, etc., who felt Williams needed to be more overtly out of the closet, or at least more overtly political in his writing. As in the Chinese Cultural Revolution, what certain activists objected to was Williams’s choice not to write gay characters as positive role models — not that he wrote any straight characters as positive roles models, either.

AF: Why now? You did this theme last year — so, why is it being chosen again?

Kaplan: Last year we planned to pay notice to the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower’s visit to Provincetown. The pandemic altered our plans. We did present live performances — not via Zoom — but not all of them could be in Provincetown itself.

As if we were back in the time of the Puritans, censorship seems cool again. Right or left, it always has to do with purity. So, as Gertrude Stein once said about her work: to focus on censorship in 2020 and 2021, it’s not repetition, it’s insistence.

AF: What’s the story with the non-Williams shows at the Festival?

David Kaplan. Photo: Ride Hamilton

Kaplan: It seems to me that, right now, consideration of Williams and Censorship should take place within the context of historical censorship. That goes back to the ancient Greek theater, which had its problem with Lysistrata, and to America in 1936 when the Federal government had a problem with the production of a Black Lysistrata. We’ll be talking about those Lysistrata productions in our graduate seminar. Onstage, we’ll be watching Mae West’s play Sex, which prompted laws in 1927 that changed what Williams could present onstage.

A lot of censorship in America has to do with the impulse to shut down what women have to say, literally hanging and burning them as witches to shut them up. We’ll be presenting a production of The Witch, written in 1616, performed by Shakespeare’s acting company, and for some reason — hmm, wonder what that is? — not published for 150 years.

AF: What’s the connection to Provincetown?

Kaplan: What defines Provincetown is that the Mayflower left. That its reputation was so bad Truro spun off their outermost territory into The Provinceland. The Puritans had fines for people who dressed outside the drab norm. It’s called “fflaunting” — two f’s. It’s 401 years later and we’re passing on the great tradition of fflaunting. With two f’s.

Robert Israel can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.

Tagged: David Kaplan, Provincetown Tennessee Williams Theater Festival