Opera Album Review: A Captivating World-Premiere Recording of One of the Most Oft-Performed Operas in the 17th Century

By Ralph P. Locke

Cross-gender disguises and comic banter liven up the melodrama in this presentation of Antonio Cesti’s famous opera, thanks to a spirited and virtuosic traversal by a mostly Italian cast.

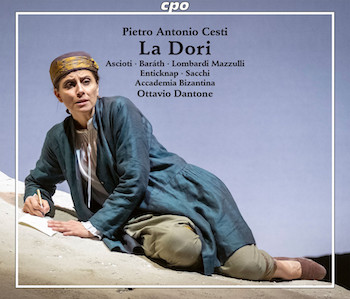

Antonio Cesti: La Dori

Francesca Ascioti (Dori/Ali), Emöke Barath (Tolomeo), Francesca Lombardi Mazzulli (Arsinoe), Rupert Enticknap (Oronte), Konstantin Derri (Bagoa), Federico Sacchi (Artaxerse)

Accademia Bizantina, cond. Ottavio Dantone

CPO 555309 [2 CDs] 161 minutes; also available on DVD: Naxos BluRay 2110676

Antonio Cesti (1623-69) was one of the formative composers of Italian opera in the 17th century: a generation after Monteverdi, he overlapped chronologically with Cavalli. He got some plum commissions, such as to provide the opera (Il pomo d’oro) to celebrate the marriage in 1666 between Emperor Leopold I (of the Holy Roman Empire, headquartered in what is today Austria) and the Infanta of Spain Margaret Theresa. (I reproduce and discuss a fascinating engraving of a scene from that opera, including a dark-skinned character representing Africa, in my book Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart, pp. 214-17.)

A recording of Cesti’s long-famous opera Orontea was much praised by record critics in 2017. (It was conducted by Ivor Bolton.) The present recording is apparently the world-premiere recording of La Dori, one of the most often-performed (and often-altered) operas — by anybody — in the 17th century. There survive at least five competing manuscripts and some 27 printed librettos! (A new libretto was necessary for each new production of almost any opera, because of cuts and new additions.)

Cesti composed La Dori, or the Faithful Slave for the court at Innsbruck (in, again, what is today Austria — specifically the Tyrol, near Bavaria). It was first performed there in 1657. Carl Schmidt, in GroveOnline, describes the work as “a masterpiece of mistaken identities, secondary love intrigues, comic interludes, rapid-fire dialogues and unexpected resolutions … [and distinguished by] the even distribution of arias and duets throughout the three acts, an effective comic element and the high quality of the music itself.”

As is typical of mid-17th-century operas, each scene progresses in a flexible way, through a free alternation of recitative-like passages and short arioso statements that, in happier or more sarcastic moments in the plot, can move suddenly into measured passages in quick triple meter that seem almost dancelike. I admired Cavalli’s mastery of this kind of musical dramaturgy in the superbly performed L’Ipermestra (led by conductor and master lutenist Mike Fentross). I was captivated here by Cesti’s similar command. Particularly satisfying are those moments where two or more voices join in song: for example, a number for two female characters (CD 1, track 11) or one for three characters: two men and a pretend-man (Artaxerxes, Oronte, and Ali; CD 1, track 21). You can hear the beginning of each track here. And the whole recording is available for free on YouTube, broken into 51 tracks (and of course is also available to subscribers of Spotify and other subscription services).

The plot involves Dori, princess of Persia, and Oronte, prince of Nicaea, who are devoted to each other but have been separated by complicated circumstances. They eventually find each other again, though not until after Oronte has heard a false report that Dori has died. (This is opera: Dori was given a love potion instead, which in this case wasn’t needed, since she already loved him.)

A scene from the 2019 Innsbruck Early Music Festival production of La Dori. Photo: Naxos.

Dori spends almost the entire opera in disguise as an Egyptian slave (male) named Ali. Dori’s sister Arsinoe is loved by Tolomeo, who spends most of the opera in disguise as a woman, Celinda (this is the double-role taken by soprano Emöke Barath). There are also comic roles for a nurse named Dirce and a boorish servant named Golo. In fact, the opera requires 10 singers, and they take 12 roles, if one counts the second identities assumed by two of them. You’ll have to follow the libretto carefully — unless of course you prefer to just listen, which I did a lot of the time, quite happily.

The performance is captivating. Recently, I was delighted to report on a new recording of Vivaldi’s Tamerlano that involved this same early-instrument orchestra, Accademia Bizantina (founded in 1986 in Ravenna, Italy). Ottavio Dantone, its music director since 1996, conducted that recording splendidly and does so again here. There are a lot of colors in his orchestra (transverse flute, two recorders, multiple plucked instruments including harp). We could have used some words of explanation about how much has been indicated in the score and how much has been added conjecturally. Some of this may go beyond what scholars can be sure was done at the time, but most listeners will be happy for the occasional variety in sounds.

Best of all, Dantone avoids engaging in the occasional lickety-split tempi that often pushed his fine singers to their limit in florid passagework in the Vivaldi recording. Of course, Cesti requires florid and propulsive singing less frequently than does Vivaldi (half a century later). But I don’t mean to exaggerate: there is (happily for us voice-lovers) some coloratura.

The singers are again ones that I had never heard before. The most familiar name here is Barath, whom I had never encountered but, I see, has been featured in important performances of Cavalli operas and in recordings of operas by Handel, Vivaldi, Gluck, and Leclair, plus an album of scenes from three Orfeo operas.

Emőke Baráth and Pietro Di Bianco in a scene from the 2019 Innsbruck Early Music Festival production of La Dori. Photo: Innsbrucker Festwochen / Rupert Larl.

Some of the singers are weak at the low end of their range (Bradley Smith or, worse, Pietro di Bianco) or unsteady in vocal production (Rocco Cavaluzzi and, again, di Bianco). But others offer consistent pleasure (Federico Sacchi: a true bass who, wonder of wonders, is also fluent in coloratura) and even true delight (countertenors Rubert Enticknap and Konstantin Derri, the latter in a comic role: the eunuch Bagoa). Best of all (that is, aside from the predictably wonderful Barath) are soprano Francesca Lombardi Mazzulli (as Arsinoe) and alto Francesca Ascioti, in the title role of Dori/Ali. Most of the singers are Italian, and they show a keen understanding of the words they are singing, perhaps especially the tenor Alberto Allegrezza as the nurse Dirce.

The recording blends three staged performances at the Innsbruck Festwochen in August 2019. Captivating photos from the production suggest how gratifying the event was — and, for once, how appropriately costumed (not updated to Nazi Germany or to Beatles-era “swinging London”). A DVD of this same production is also available from Naxos (regular and BluRay). I’ve watched some bits on YouTube: the eunuch Bagoa has much more “presence” in the action than if you’re just hearing him. But, either way, a greatly welcome release!

Excellent booklet-essay, full libretto, and clear translations of both.

Ralph P. Locke is emeritus professor of musicology at the University of Rochester’s Eastman School of Music. Six of his articles have won the ASCAP-Deems Taylor Award for excellence in writing about music. His most recent two books are Musical Exoticism: Images and Reflections and Music and the Exotic from the Renaissance to Mozart (both Cambridge University Press). Both are now available in paperback; the second, also as an e-book. Ralph Locke also contributes to American Record Guide and to the online arts-magazines New York Arts, Opera Today, and The Boston Musical Intelligencer. His articles have appeared in major scholarly journals, in Oxford Music Online (Grove Dictionary), and in the program books of major opera houses, e.g., Santa Fe (New Mexico), Wexford (Ireland), Glyndebourne, Covent Garden, and the Bavarian State Opera (Munich). The present review first appeared in American Record Guide and appears here with kind permission.

Tagged: Accademia Bizantina, Antonio Cesti, La Dori, Naxos BluRay, Ottavio Dantone

[…] the high quality of singing in most of the early-opera recordings that I got to review, including Cesti’s La Dori, Vivaldi’s Tamerlano, Hasse’s Enea in Catonia, and Gluck’s […]