Film Review: “Truman & Tennessee: an intimate conversation” — He Said, He Said

By David Greenham

Truman & Tennessee is a meticulously researched and edited documentary about two gay men and their differing commitments to art.

Truman & Tennessee: an intimate conversation. Directed and Produced by Lisa Immordino Vreeland. Edited by Bernadine Colish. Shane Sigler, Director of Photography. Original music composed by Madì. Produced by Mark Lee, Jonathan Gray, and John Northrup. Co-Executive Produced by Brian Devine and Brook Devine. A Fischio Films Production in association with Peaceable Assembly and Gigantic Films. Screening on Kino Marquee

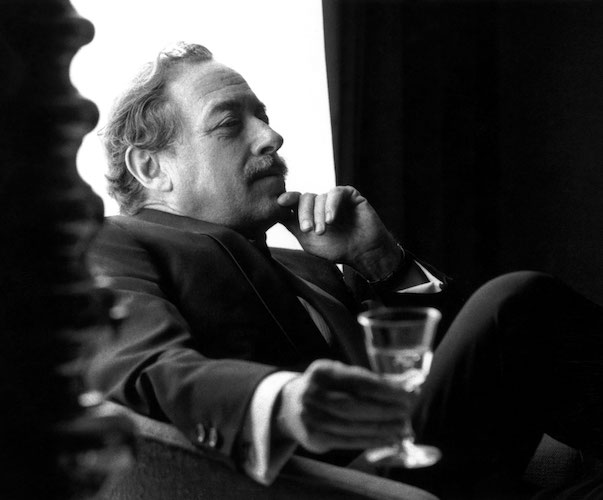

Tennessee Williams. Photo: Hulton Archive. Courtesy of Getty Images

Towards the end of Lisa Immordino Vreeland’s meticulously researched and edited documentary Truman & Tennessee, Truman Capote casually tells Dick Cavett, “I’ve known Tennessee a long time. Our friendship has had its ups and downs.” He adds, “Here is a man who has devoted his whole life to his art….”

Truman & Tennessee is about two gay men and their differing commitments to art. Williams notion of creativity focused on the written word; for better or worse, Capote saw the text on the page as a vehicle that could transport him to another world, the realm of celebrity. In this sense, his art anticipated the efforts of the Kardashians and social media influencers today. For better or worse, his imagination was dedicated, at least in part, to joining up with the upper class and the well known.

Williams provides a wistfully incomplete description of their literary motivation: “Writing is simple impulse. At heart a simple function…a simple man’s way of calling out to others.” The documentary digs into what most of us already know: neither Williams nor Capote were simple men.

These two literary lions of the 20th century were life-long friends. Capote claims that they met in in 1940, when he was just 16. That’s probably not true, but they did have much in common. Both hailed from the Deep South: Williams, who was 13 years older, was from Columbus, Mississippi. Capote was born in New Orleans. Each writer was a prodigy, came from a broken home with an absent father and, unfortunately, waged a continual struggle against depression and alcoholism. And, of course, both were openly gay at a time when it was generally not accepted or safe to be publicly ‘out.’ A narrator informs us that they “goaded and supported one another in the agonizing quest to turn their life into art.”

Truman & Tennessee is an obvious labor of love for its creators. Vreeland has recruited her famous actor friend Jim Parsons (Capote) and Zachary Quinto (Williams) to provide effective voiceover impersonations of the pair, their words taken from the subjects’ letters and other writings. By drawing on the intimacy of first person accounts, Vreeland augments dozens of interview clips from various television talk shows that are included in the film. Most of these snippets are entertaining and, because they’re public presentations, there is a sense we are watching performance art, especially with Capote, who worked to become a pop icon. (Because of his eccenric character and acerbic nature, Capote’s been the focus of many commercial films and stage plays, including the 2017 American Repertory Theatrer production WARHOLCAPOTE, which I reviewed for The Arts Fuse.)

The documentary is also generously peppered with clips from films sourced from the writers’ most famous works. The segments are adroitly placed to hammer home a thematic point or to set up a chronological transition.

As we weave through their parallel loves, losses, triumphs, and tragedies, Williams becomes the more sympathetic figure His sorrow about life’s injustices is never far beneath the surface. Capote embraces a public persona that serves as an impregnable wall — he is defensive rather than revealing. He’s funny and curious, but rarely warm. His frosty snap can be amusing but, based on his writings, this is an armored persona.

Still, each could be spiky when attacked: Williams could give as good as he got. For example, there is a deliciously snarky back and forth account of their trip to an Italian island with their respective partners, Frank Merlo (Williams) and dancer Jack Dunphy (Capote). Williams snarls: “Truman has been wrapped around Jack like a boa constrictor practically every minute, except when he is making little invisible pencil scratches in a notebook that is supposed to be his next novel.” Capote counterstabs: “Merlo and Tenn latched on to us like barnacles. Taken in tiny doses, I’m really fond of them both, but darling, I can’t tell you what it’s been like: Frankie nags Tennessee all day and night, and Tennessee, I’ve discovered, is a genuine paranoid.”

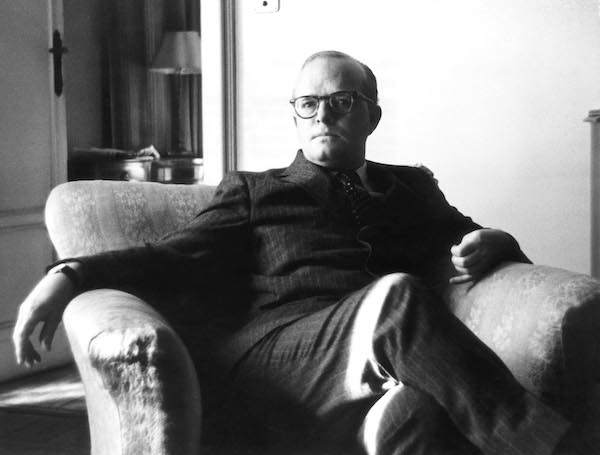

Truman Capote in Milan negotiating a contract for his new nonfiction novel In Cold Blood. Photo: Keystone/Getty Images.

Back-to-back clips with the sharp British TV presenter David Frost reveal a stark difference between the two writers. Frost prompts each on the subject of love. Capote dryly answers each question, but deftly avoids taking the bait. In the end, he makes a joke of his answer. But Williams pauses and contends. “Love is a feeling, isn’t it?,” he asks innocently. He refers to sexual love and “something beyond it.” When Frost pushes and asks for more, Williams starts to speak, but cuts himself off with an uncomfortable laugh, “I’m talking too intimately to you. Let’s get on to something more general.”

The varied and unusual music of the Italian composer Madì wafts throughout the film, which he scored during the 2000 spring lockdown in Italy. At the time, this countrywide shutdown made international news. Madi put the horrific experience to good artistic use: his score reflects a sense of feeling cornered, and that is very appropriate for both Williams and Capote, who battled powerful inner demons.

Their lives crumple in parallel. Williams was killed by a drug overdose in 1983 and Capote died 18 months later of liver disease brought on by alcohol and drug use. On the one hand, the film is about perceiving the act of writing as a product of individual heroism, an assertion of value in a hostile world. “All writing, all art is an act of faith. And therefore is an act of love,” wrote Capote, while Williams proclaimed, “If you can’t be yourself, what’s the point of being anything at all.”

Yet Truman & Tennessee also examines the trajectory of a pair of broken lives that ended in sadness — despite what they accomplished. And that puts some melancholic sting into the film’s celebration of art. At one point, Capote’s novel Other Voices, Other Rooms is quoted: “What we most want is only to be held…and told…that everything is going to be all right.” Both writers would testify that we don’t always get what we want.

David Greenham is an adjunct lecturer of Drama at the University of Maine at Augusta, and is the executive director of the Maine Arts Commission. He has been a theater artist and arts administrator in Maine for more than 30 years.

Tagged: David Greenham, documentary, Lisa Immordino Vreeland, Madì, tennessee-Williams, Truman & Tennessee