Book Review: “Hard Like Water” — The Revolution Will Be Eroticized

By Maxwell Olin Massa

There is no gainsaying that Hard Like Water is, in English, an important book, if only because of its refreshingly sensual vision of the appeal of the Cultural Revolution.

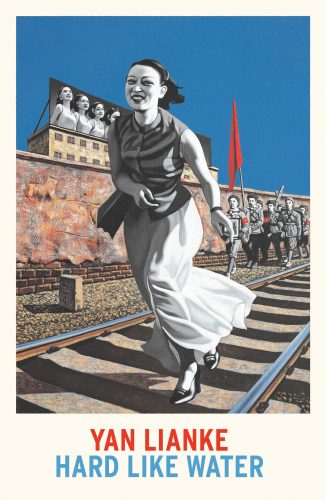

Hard Like Water by Yan Lianke. Translated from Chinese by Carlos Rojas. Grove Atlantic, 432 pages, $27.

The more you understand of Chinese history, particularly the Cultural Revolution, the more you will get out of Yan Lianke’s powerful 2001 novel Hard Like Water (坚硬如水). His narrative looks at his country’s cultural upheaval through the lens of a very physical romance, and the result is a blend of the sexual and the political that, even for Western readers who come with limited knowledge of China’s convulsions in the ’60s, offers considerable rewards.

The more you understand of Chinese history, particularly the Cultural Revolution, the more you will get out of Yan Lianke’s powerful 2001 novel Hard Like Water (坚硬如水). His narrative looks at his country’s cultural upheaval through the lens of a very physical romance, and the result is a blend of the sexual and the political that, even for Western readers who come with limited knowledge of China’s convulsions in the ’60s, offers considerable rewards.

The plot revolves around the love affair that develops between Gao Aijun, a demobilized soldier, and Xia Hongmei, a dissatisfied city girl in a small village, who are united in their effort to bring the reputed joys of the Cultural Revolution to Gao’s hometown, Chenggang (程岗). Descriptions of their frequent sexual encounters are vividly erotic, and that sensuality is a crucial part of the book’s daring realism as it examines the kinds of desires (physical, social) that pervaded the lives of ordinary people. Yan talked about his approach to writing the novel’s sexual encounters in a 2014 interview with Ulrich Kautz (高立希), one of Germany’s best known Sinologists, at the Uebersee Museum (translation mine):

Writing sex [scenes] is the greatest test of a mature writer. When well-written, sexuality conveys love; when the writing’s bad, love will be reduced to sex. Sexuality is a supreme reflection of human nature, and in fiction it directly expresses an author’s vision of the world – given that, there’s a fair amount of sex in this work. But I invite everyone to trust that this is not a pornographic novel: it is purely an author’s musing on love and human nature. […] When it comes to writing “the beauty of sex” I cannot reach D. H. Lawrence’s heights, but I hope that I achieved his elevation in my thinking about the world and about human nature. Every reader who is familiar with the history of China will recognize this book’s sincerity.

Hard Like Water makes good on Yan’s claim: it succeeds in using sensuality as a means to illuminate the period’s interwoven desires, from the physical to the ideological. Gao is all nerve endings, his eyes and ears are always on the alert, his hands ever eager to reach out and touch people and things. The revolution itself has become sexual for him, and Yan brilliantly makes us see how odd — yet natural — that is.

But, if the novel dovetails sexuality and revolution, it also depicts the conservatism that opposes sexual freedom. The bulk of the novel’s action takes place in the purported hometown of the Cheng brothers (the elder Cheng Hao and the younger Cheng Yi, actually from Luoyang), who were the forerunners of the Cheng-Zhu school of Neo-Confucianism. This school of thought was deeply dedicated to tradition, the rigid grayness of social conformity. Cultural tokens that signify repression abound, from Gao’s mother’s bound feet to his wife’s rigid rejection of sexual enjoyment. Against this allegiance to the hidebound, Yan suggests the possibility that a highly-charged mind, like Gao’s, will become manic about the need to make revolution — everywhere and in everything. But, as Yan is no doubt aware, the value of this response is complicated by the fact that Mao’s great proletarian movement turned into a horror. The period’s commitment to self-expression, its call for liberation, became deeply destructive. By examining this intractable conflict — between freedom and containment — without flinching, Yan proves to be a social analyst of impressive power.

As to the translator, Carlos Rojas is an established figure in this field and has brought many of Yan’s other works to the English-speaking market, including The Explosion Chronicles, Three Brothers: Memories of My Family, Lenin’s Kisses, Four Books, The Years, Months, Days, and The Day the Sun Died. Given how the narrator shifts tones among various registers, the lyrical as well as the ideological, Rojas’s past experience proves to be invaluable. For example, the way he subtly links phrases like “mountains and rivers full of love” with “the road of socialism stretching ahead” reflects the electrifying extremism of Gao’s vision: his idealism arouses him. Transferring this point from Chinese to English is quite a feat. Rojas is at his best when tackling lengthy prose descriptions which articulate the narrator’s thoughts as well as his reactions to the environment around him.

Yan Lianke speaking in Paris in 2010 : “I used to assume history and memory would always triumph over temporary aberrations and return to their rightful place. It now appears the opposite is true.”

There are some defects. Rojas’s handling of Yan’s dialogue is much too clean and conventional. He misses the novel’s linguistic idiosyncrasies. For example, at one point the narrator tells us that he has just delivered a lengthy talk in “a mix of local dialect and military-accented Mandarin.” But the monologue, which took up the previous five pages, was far from being a passionate harangue that darted back and forth between different verbal registers. In fact, its unity of tone approached the bureaucratic. The starkest instance of this flattening of the spoken word is when Secretary Tian becomes so drunk he falls under the table. There he delivers the following speech:

Deputy Mayor Gao, after you are promoted to mayor or Party secretary, I don’t dare hope to become deputy mayor, but you must at least help me transfer my residency permit. I don’t want to have to spend five years working as a secretary, with my household residency permit still assigned to my family’s original mountain district!

An incredibly lucid performance for a local bureaucrat who just hit the floor!

There are a few other minor issues. Yan’s skill at concrete description does not extend to the environment: one struggles to get a sense of the look and scale of Chenggang. But there is no gainsaying that Hard Like Water is, in English, an important book, if only because of its refreshingly sensual vision of the appeal of the Cultural Revolution. And it should be pointed out to American readers that, in our era of heightened political tensions, with conservatives and progressives polarized, the experience of an ambitious Chinese revolutionary convinced of his correctness has much to tell us about ourselves.

Maxwell Olin Massa is a graduate of the Hopkins-Nanjing Center and currently works as a policy analyst in the DC area. In addition to having written on the rule of law, he is also a staff writer for Third Factor magazine and published House of Apollo, a novel of ideas, with Whiskey Tit Books in 2020. He was even a Chinese TV host for a year, once upon a time.