Book Review: “Warhol” — Pop Art’s Timeless Impresario

By David Stewart

Accessible to the art-loving novice, Blake Gopnik’s Warhol suggests that his subject’s marketing genius doesn’t have a time limit.

Warhol by Blake Gopnick. Ecco, 976 pages, $45.

Campbell’s Soup, Brillo Boxes, Marilyn Monroe, and Chairman Mao. A sampling of the subjects for iconic art pieces made by a man who became synonymous with pop art: Andy Warhol. Blake Gopnik’s comprehensive biography is a sprawling, richly detailed 900 pages that isn’t content to cover the unsavory and salacious details of Warhol’s New York life, from his Silver Factory parties to his night-owl status at Studio 54. The Washington Post’s former art critic pays careful attention to the early years of Andrew Warhola, the young Dadaist who plied his artistic trade in Pittsburgh before moving to New York City in 1949, living there until he died in 1987.

Campbell’s Soup, Brillo Boxes, Marilyn Monroe, and Chairman Mao. A sampling of the subjects for iconic art pieces made by a man who became synonymous with pop art: Andy Warhol. Blake Gopnik’s comprehensive biography is a sprawling, richly detailed 900 pages that isn’t content to cover the unsavory and salacious details of Warhol’s New York life, from his Silver Factory parties to his night-owl status at Studio 54. The Washington Post’s former art critic pays careful attention to the early years of Andrew Warhola, the young Dadaist who plied his artistic trade in Pittsburgh before moving to New York City in 1949, living there until he died in 1987.

Gopnik presents a vivid portrait of Pittsburgh in the ’40s, focusing on the cultural and sexual barriers Warhol had to grapple with, paying particular attention to the local police’s indifference to homophobia. The artist was ambitious and enterprising, dreaming of rubbing shoulders with his literary hero-cum-fellow-gadabout, Truman Capote. By the time Warhol moved to New York he was beginning to self-consciously shape his pop art persona and win over patrons. His ironic fusion of popular culture, politics, and high art– marrying the museum to Madison Avenue — placed him at the vanguard of pop art, among his contemporaries Robert Rauschenberg and Roy Lichtenstein. Gopnik points out that Warhol initially made his name in Los Angeles, where he immortalized Elizabeth Taylor and Elvis on silkscreen canvases. Hollywood was an elemental ingredient in Warhol’s success. A salutatory house party tossed by Dennis Hopper and Brooke Hayward inspired Warhol to rent hot dog carts for his infamous Silver Factory soirees on East 16th Street.

It was in the ’60s that Warhol hit his stride, creating the “cool” persona of an introverted extrovert, decked out in leather jacket, sunglasses, and an iconic silver wig. He attracted and repelled critics with his paintings of Campbell’s Soup cans and of Jackie Kennedy just before and after her husband’s assassination. Also controversial were his prints of the electric chair used for the Julius and Ethel Rosenberg executions. He delighted in leaving interviewers perplexed, writing prophetic quips about how “in the future, everyone will be world-famous for 15 minutes.” His riposte to Hollywood was to create underground film epics such as Sleep and Chelsea Girls. And he influenced the music world by way of his Factory’s in-house band, the Velvet Underground.

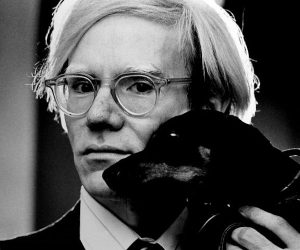

Along with Warhol, the infamous Factory regulars show up in Gopnik’s book, usually sprawled out on Warhol’s sofa. They range from speed-fueled fashionista Edie Sedgwick to the mentally disturbed Valerie Solanas, who shot Warhol in his office in 1968. Too many books have been written about Warhol’s party guests, and Gopnik knows this, so he compresses their stories in order to make room to examine how the fickle Warhol treated members of his inner circle. In many ways, Warhol anticipated the role of the reality television showrunner. In his movies with filmmaker Paul Morrissey the artist set out to capture the spontaneous decadence, the embarrassingly high strung emotionalism, of the Factory’s superstars. This obsession with documenting everything around him suggests that Warhol inadvertently spearheaded the Instagram era — he carried his Polaroid SX-70 Land camera with him to almost every social event.

Andy Warhol with Archie, his pet dachshund. Photo: Jack Mitchell/Wiki Common.

Gopnik hones in on Warhol’s connections with film. In his diaries, the artist comes across as a highly opinionated cineaste, praising Luis Buñuel’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, appreciating the movies of Jean Cocteau, denigrating Midnight Cowboy’s party sequence. His connection to Hollywood was mainly through his portraits of celebrities. He made a cameo appearance opposite Elizabeth Taylor in The Driver’s Seat and appeared on The Love Boat. He experimented with television in the mid-’80s with a short-lived MTV talk show that included Frank Zappa and Debbie Harry as guests.

Warhol’s legacy has less to do with how his pop art rebelled against abstract expressionism than his powers as a charismatic, monetizing impresario in the worlds of art, music, and politics. Like his salacious design for the cover of the Rolling Stones’ Sticky Fingers album, Warhol created a product that infused chic consumerism with an air of sexual rebellion. Accessible to the art-loving novice, Blake Gopnik’s Warhol suggests that his subject’s marketing genius doesn’t have a time limit.

David Stewart is a professor of Film and Media Studies at Plymouth State University. Along with teaching, he is a documentary researcher and contributing writer for The Film Stage and PleaseKillMe.com. His film credits include Amy Scott’s documentary Hal and Marielle Heller’s The Diary of a Teenage Girl. He lives outside of Boston with his family and beloved Fender acoustic, Nadine.

An interesting review, though I don’t agree that Warhol films anticipated reality TV. Quite the opposite: Warhol’s films are slow, slow, slow, passive, passive, passive, leaving in all the boring parts. Reality TV is hyper-edited, cutting away anything slightly slow, anything which is not seen as exciting and dramatic.

The commodification and Instagram-ization of our culture can to some degree, certainly be laid at the feet of Warhol. However, his films cut against that grain, as Gerald says above. They’re more Tarkovsky than Kardashian and I’ve always wondered about that. Given the quick, if not instant gratification feedback loop in Warhol’s work, how did he arrive at that approach to film making? I tend to think it was about time and control, rather than any deeply-held cinematic ethos. Plant the camera, let it run and don’t think about anything else.

Not: “and don’t think about anything else.” I mean: “And you can think about something else.”