Theater Commentary: A Time for Tragic Reflection

By Bill Marx

“We can, of course, be deceived in many ways. We can be deceived by believing what is untrue, but we certainly are also deceived by not believing what is true.” — Søren Kierkegaard

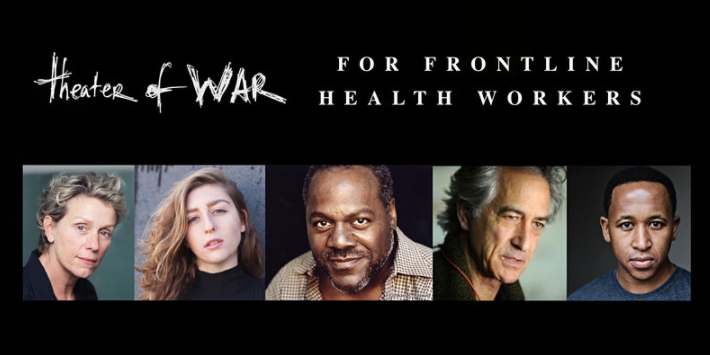

Can Greek Tragedy help us make sense of the global challenges we face today, from COVID-19 to the climate crisis? I think so, and kudos to Bryan Doerries, the producer of Theater of War productions, for making the case. For months he has been directing (via Zoom) dramatic readings by well-known performers (Bill Murray, Frances McDormand, Jeffrey Wright, Adam Driver, Jesse Eisenberg, Paul Giamatti, Jake Gyllenhaal, and others) of scenes from ancient Greek plays. These forceful renditions (at least those I have seen, particularly McDormand’s crazed Hercules) have been followed by discussions enlivened by stories and insights from nurses, doctors, first responders, and other health care professionals, along with concerned citizens and others impacted by the pandemic. The chimera of catharsis remains as elusive as ever, but these productions have been moving homages to the power of theater, its ability to crystallize human contradictions and clashing desires (conscious and unconscious) through the display of humanity in extremis. Will contemporary stage companies take up the challenge and produce these texts? I am not optimistic.

The problem is not that scripts such as Sophocles’s Philoctetes and Women of Trachis are limited to illuminating the trauma of disease and how it can be ameliorated. Doerries makes that point in a recent Project Syndicate commentary, where he argues that Greek Tragedy can help us in our battle to comprehend and confront climate change. Scientists can state the facts and tell us what we can do about the fix we are in, but poets can make us feel the agonizing impact of the irremediable damage we’ve already done, and dramatize the need for an urgent change in direction. He believes that we (theater practitioners as well) should rethink our perception of Greek tragedies if we are going to appreciate their significance now.

We need a language to convey the gravity and complexity of the global tragedy that is unfolding, and the ancient Greeks supply it. Their tragedies are stories of people learning too late (usually by milliseconds). Their characters doggedly pursue what they believe to be right, barely comprehending the forces they face — chance, fate, habits, governments, gods, the weather. By the time they do, the characters have unwittingly made an irreversible — and devastating — mistake.

For centuries, Greek tragedies have been viewed as pessimistic expressions of a fatalistic society, which depict the futility of fighting destiny. But, for the Greeks, the effect of these stories may have been counterintuitive. By showing people just how narrow and fleeting their power to determine their own future was, the tragedies discouraged apathy. Highlighting how devastating self-delusion can be encouraged awareness. And providing the language for describing difficult experiences enhanced agency.

I agree that the language of Greek Tragedy has the poetic and intellectual heft to convey the bewilderment, pain, and devastation that has followed the gutting of the global climate by the fossil fuel industry. But his notion that some view these plays as “pessimistic expressions of a fatalistic society” is self-defeating and unjust to the unruly beauty and distinctive value of these texts. To my knowledge, major critics and stage directors have rarely dismissed these scripts as mere bummers. That is the stance of publicists, who don’t think tragedy will “sell” to the public. Frankly, an opposite reaction is more symptomatic of the popular (and academic?) imagination — affliction in Greek Tragedy comes with an inevitability that generates the heroic splendor of individual resistance.

In truth, what contemporary theater fears is not that Greek Tragedy is too despairing or that it encourages defeatism. The threat is that tragedy contradicts our demand for the feel-good, doesn’t meet our appetite (at least in America) for theater that is uplifting and empowering. The stage is expected to offer some sort of ameliorative vision, either from a facile conservative or progressive perspective. Ticket buyers are handed superficial Band-Aids and sent on their enlightened way, an artistic dead end that has been reinforced by the pandemic. The postpandemic programming, at least at this point, looks as if it will be serving up the equivalent of pep pills for the exhausted.

Euripides, our absurdist contemporary.

Greek Tragedy is radical theater because it is rooted in irremediable pain and loss, wounds that are impossible to repress, particularly the ghosts of war. As Russian writer Adam Tertz succinctly put it: “The past says to us through its burial mounds: ‘Do you think I was less real than you?'” That pertains as much to the voices of extinct species as it does to the memories of the butchered. Is acknowledging history’s curse an upper or a downer? Philosopher Simon Critchley offers a response in his recent book Tragedy, the Greeks, and Us, “Tragedy is neither simply affirmative or negative, neither optimistic or pessimistic. It cannot be defined by affixing either a plus or a minus sign. And such oppositions are pretty fatuous…. It gives us a genealogy of who we are, an account of our origins and how the curse of the past can unknowingly take shape in the present, and we don’t see it and we rage when we are told what it is.” Doerries bows to pressure to add a “plus” sign when he suggests that the language of Greek Tragedy somehow enhances agency. “What are we supposed to do?” is a question that choruses ask throughout Greek Tragedy. No answer is forthcoming. For me, Greek Tragedy is more of a diagnostic tool than a healing salve; these plays are poetic X-rays that show the patient (in this case society) what it doesn’t want to see — that it is ill.

Ironically, in order to domesticate Greek Tragedy so that it enhances agency, you have to overlook many of them, certainly the majority of those written by Euripides, who calls into question some of the more modulated vision of human irrationality found in the plays of Sophocles and Aeschylus. I say apparent, because some of these texts are far more anarchistic than they are given credit for: for example, the over-the-top lamentation that dominates Sophocles’s Electra. The tragicomic universe of Euripides, populated by unpredictable gods who whisk the child-killer Medea from those seeking to punish her, is the theatrical turf of Artaud, Brecht, Pinter, Beckett, Pirandello, Shakespeare, Jonson, Edward Bond, and Sarah Kane.

Tellingly, Doerries does not take up a quality, besides language, that makes Greek Tragedy of salient value today. That might be because it may scare off American audiences fed on reassuring family dramas and rousing musicals. The scripts of Euripides & Co. are diagrams of societies in distress; their conflicts pit irreconcilable positions against one another. These headbutting oppositions are symptomatic of a political meltdown — and that makes these plays disturbingly modern in our polarized time. “It is not surprising,” writes Miriam Leonard in her 2015 book Tragic Modernities, “that tragedy was the explanatory framework that thinkers have had recourse to in times of emergency. The French Revolution and the Industrial Revolution that came in its wake, the two World Wars, the long aftermath of the Shoah, decolonization — all of these events have given rise to profound reflections on tragedy and the tragic.” Aside from Doerries, few theater practitioners have grasped that the crisis of climate change calls for tragic reflection, perhaps even demands that we stage tragedies, old and new. Perhaps it will take a peek over the edge of the climate cliff — as when we breach a crucial tipping point in the Earth’s temperature in five years — for us to confront our Oedipal blindness.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of the Arts Fuse. For just about four decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and the Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created the Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.