Book Review: “Renato!” — Novelist Eugene Mirabelli, Creator of Inwardness

By Roberta Silman

What a pleasure it is to revel in this work, which expresses enduring values in such an original way.

Renato! by Eugene Mirabelli, McPherson & Company, 592 pages, $20

Buy at Bookshop

As I was reading Eugene Mirabelli’s wonderful novel Renato!, which is a terrific way to begin the new year and possibly a new era (“the Biden era,” I heard it called recently on TV), I was reminded of a quotation from Susan Sontag in her Paris Review interview (The Art of Fiction, Number 143):

A novel worth reading is an education of the heart. It enlarges your sense of human possibility, of what human nature is, of what happens in the world. It’s a creator of inwardness.

How beautifully that describes this trilogy, which is made up of three earlier novels — The Goddess in Love with a Horse, Renato, the Painter, and After Alba — and which, I hope, will bring Mirabelli, who was born in 1931, the wide readership he deserves.

For here is a voice worth listening to — an erudite writer with an exuberant style telling us a story of a Sicilian family over the last 150 years that will expand your vision, amuse you, instruct you about all sorts of things you never dreamed would interest you but do, and, perhaps most important, make you remember your own childhood and the people you love even more vividly than you do. As Douglas Glover observes in the Introduction: “The overall structure — the sudden shifts of story line and rapid changes of time and place — has the feel of life itself.”

For here is a voice worth listening to — an erudite writer with an exuberant style telling us a story of a Sicilian family over the last 150 years that will expand your vision, amuse you, instruct you about all sorts of things you never dreamed would interest you but do, and, perhaps most important, make you remember your own childhood and the people you love even more vividly than you do. As Douglas Glover observes in the Introduction: “The overall structure — the sudden shifts of story line and rapid changes of time and place — has the feel of life itself.”

As he tells the story of the Cavallu family, Renato reminds us of our own family elders sitting before a fire on a snowy day, drinking mulled cider, and telling what they remember with uncommon ease and an unerring eye for detail. Here he is in the first volume talking about Baldo, whose sister, a widow of 29, has been impregnated by Angelo’s rapscallion son Fimi who is 18:

Baldo’s favorite story was how when Garibaldi and his Red Shirts came ashore to liberate Sicily the first thing they did was ask for a map. “Sicily wasn’t on their maps! You see, the Northern Italians have always felt, deep in their hearts, that Italy stops at the beach in Reggio Calabria. On the other side of the water is the Island of Sicily which to them is not Africa but not really Italy, either. So nothing changes here. The important thing is not politics,” said Baldo. “The important thing is work, to have children, and to hold your land from generation to generation.”

The fact that Fimi, like his father, is half man, half horse, is only incidental, and with time the men become all man, lusty as ever, and the women stay beautiful even when they are old and even after most of them leave their cherished Sicily and put down roots in Boston.

Renato, whose name means reborn and is not only the narrator but also the protagonist of this work, takes us into a world that is as magical as it is convincing. The adventures of this enormous clan range through generations and, as we suspend our disbelief, we are plunged into a mash-up of time that zigzags among stories-within-stories, tangential essays about the history of Sicily, the myths, both real and imagined, generated by the family’s immigration to Boston, the history of the airplane, their very own aeronautical inventor Aldo, Aldo’s marriage to Molly, the mysterious appearance of Renato on the family’s doorstep, his youth and adolescence and finally his marriage to Alba, whom he first knew as a teenager and to whom Fate seems determined to lead him. Throughout there are digressions on artists and their tumultuous lives, from Cellini to Maillol to Elaine de Kooning because, once Renato has become an artist, he goes to the Museum of Fine Arts School in Boston and eventually teaches at the Copley College of Arts.

Circles upon circles that somehow come back to the family, which is one of the pillars of this book in much the same way that the Compsons are one of the pillars in Faulkner. Here is a reminiscence about New Year’s Day in 1976, a hundred years after Baldo. Renato’s uncle confesses how “dazzled” he was by Darwin and how puzzled he was by the notion of God:

“The longer I think about life, the more mysterious it gets,” Niccolo said. “We began in some protoplasmic slime or green algae and here we are sitting around this table discussing our own evolution. It’s stunning. I haven’t thought this through but, despite the chanciness and accidents and despite all the randomness, there appears to be such a purposeful drive that … I don’t know what to think.”…

“I prefer not knowing what to think,” Zitti [another uncle] announced. “I’ve always been a rationalist and a skeptic—“

I laughed. “You?” I said, interrupting him. “When did you become a rationalist and a skeptic? You must be joking.”

“No. Remember, I’ve always liked Montaigne, a wonderfully curious and skeptical man. The older I get, the more I appreciate his refusal of certainty.” He smiled. “He’s an Italian, you know, transplanted to France.” Zitti regarded French intellectuals as foppish dilettantes, and for those French thinkers or artists he did admire, he claimed they had Italian backgrounds.

“Can’t we talk about something real for a change?” Candida said.

Haunting this consistently interesting and always curious family is a carefully guarded secret having to do with Renato’s parentage. And then there is Renato’s life with Alba: their quirky marriage in Boston, which involves younger women (one is the mother of their third child Astrid, sometimes called Galaxy), and their separation as Renato makes one last try toward success as a painter. That success finally arrives with a bitter tinge — it is after Alba has unexpectedly died. In short, this is a family that, from the outside, looks nuts but, like many families, seems to thrive on its own inner logic — and a marvelous talent for laughter and arguments and games and good sex, often surrounded by dappled sunlight and flowing white dresses while they participate in family dinners and reunions that have a comforting sameness about them.

The second half of the book is darker. Renato has moved to his studio so he is living in Boston. Alba is across the river in Cambridge. Now retired from teaching, he wants to give the painting one last try, but into his life comes Avalon, the daughter of old friends, and her son Kim. And a host of friends, all with a slew of ideas and opinions. Meanwhile Renato’s children will never understand why their parents are living apart and a sleazy gallery owner named Leo Conti exerts the kind of push me, pull you tension in Renato’s life that only agents or artists’ representatives can. As events unfold, there is more plot, which I won’t reveal, and more sorrow.

The final volume in the trilogy, After Alba, focuses on Renato’s survival after the death of his wife; it is interspersed with letters to Alba and conversations with her that anyone who has lost a beloved spouse will understand. Mirabelli also captures the confusion that comes from the realization that you have been guilty of squandering love when you had it. Questions are also raised about death and mortality, questions you never think you will have to confront when you are young or even middle-aged. It is at the end of this book that readers will feel that “inwardness” Sontag prizes in this review’s opening quotation.

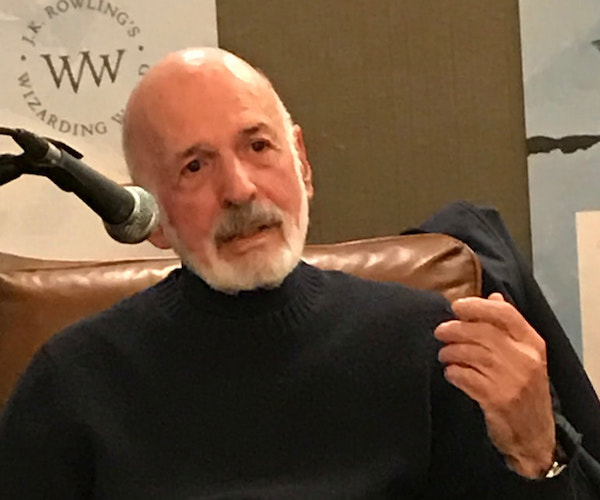

Author Eugene Mirabelli — he should be a national treasure. Photo: McPherson & Company.

Here is Renato, who is hardly the fool he sometimes pretends to be, trying to make his young boarder Avalon understand why he is living apart from Alba:

“I haven’t left, I’m just living here in my studio. Maybe I’m not living with her because I want to paint. Maybe I’m tired of being managed. Or maybe I don’t like living with a person who writes gallery reviews for the New England Newsletter, celebrating assholes. My first mistake was teaching her how to look at a painting. Now she thinks she’s a critic. I love Alba but she’s a complex subject, too fucking complex to talk about, and I wasn’t kidding when I said I’d be lost without her.”

And here he is after she is gone:

Alba, I have to tell you they’re carving out a big new shopping plaza on the next hill beyond Big Valley Farms. And it’s amazing how rapidly they’re building those condos where the Four Seasons Gardens used to be. I pass it two or three times a day, and already I can’t remember exactly where the old Franklin house stood. The places you and I used to walk are getting erased — everything is getting erased, and there’ll be no memory of us walking through that field, because memories wither when you have them all by yourself.

In his memoir Speak, Memory Vladimir Nabokov reminds us of his mother’s creed: To love with all your soul and leave the rest to Fate. The whole Cavallu family seems to live that way, and so do their many friends. Which is why they stick so firmly in the mind and why their antics are so entertaining, if also sometimes contradictory. People have talked about the operatic flair apparent in Mirabelli’s work and often cite the Italian operas. But for me Renato! brings to mind Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro, which is so wonderfully entertaining but contains layers of meaning beneath all the high-jinks. And which addresses so many questions about the human condition.

What a pleasure it is to revel in this work, which expresses enduring values in such an original way. Eugene Mirabelli, whom one reviewer described as being “of a certain era,” has written a beautiful and ambitious novel that will resonate not only with his generation, but also with the young, and especially with those who love really good writing. He should be a national treasure, and we are lucky, indeed, to have his enchanting Renato!.

Roberta Silman is the author of four novels, a short story collection and two children’s books. Her new novel, Secrets and Shadows (Arts Fuse review), is in its second printing and is available on Amazon and at Campden Hill Books. It was chosen as one of the best Indie Books of 2018 by Kirkus. A recipient of Fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts, she has reviewed for the New York Times and Boston Globe, and writes regularly for the Arts Fuse. More about her can be found at robertasilman.com and she can also be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.