Book Review: “This Is Bop” — A Biography of Jon Hendricks, Master of Vocalese

By Steve Provizer

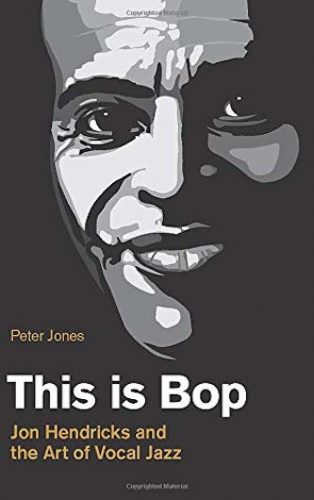

This Is Bop: Jon Hendricks and the Art of Vocal Jazz by Peter Jones. Equinox Publishing (UK), 256 pages, $36.

This biography provides a solid look at Jon Hendricks’s life and career; a well-rounded picture that is neither a hagiography nor a hatchet job.

Buy at Bookshop

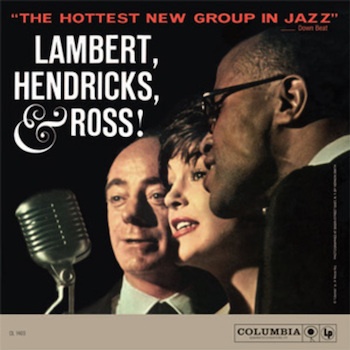

I’ve been an admirer of vocalist and lyricist Jon Hendricks since I first heard him with his most well-known group, Lambert, Hendricks, & Ross. (Arts Fuse appreciation of the late Annie Ross.) The lyrics he wrote, as well as the one meeting I had with Hendricks, made me curious to learn more about him. Happily, This is Bop presents a solid look into Hendricks’s life, a well-rounded picture — neither hagiography nor hatchet job — that helped answer many of the questions I had about the gifted musician and his career.

I’ve been an admirer of vocalist and lyricist Jon Hendricks since I first heard him with his most well-known group, Lambert, Hendricks, & Ross. (Arts Fuse appreciation of the late Annie Ross.) The lyrics he wrote, as well as the one meeting I had with Hendricks, made me curious to learn more about him. Happily, This is Bop presents a solid look into Hendricks’s life, a well-rounded picture — neither hagiography nor hatchet job — that helped answer many of the questions I had about the gifted musician and his career.

Starting in the late ’70s, I had transcribed arrangements of a number of Lambert, Hendricks, & Ross songs and performed them with groups of my own. In 1981, when I was living in Washington, DC, Hendricks came to town and I managed to arrange an informal interview with him. The impression I came away with was of a smart, gregarious man who was performing for me — not actually connecting. Anything I asked about seemed to be channeled into a narrow range of acceptable, predetermined areas, and returned back to me with a well-rehearsed answer. If such an oxymoron is possible, he seemed to be a kind of spiritual con man. And Jones’s book at least partially corroborates that impression.

Jones chronicles how, throughout his life, the charismatic Hendricks never escaped the complex, difficult nature of his childhood. His father was a ne’er-do-well drunk until he found religion and became a preacher in the African Methodist Episcopal Church. The church moved the family from one location to another while a strict regimen of prayer was enforced in the house. John was the ninth child and seventh son (the book does not say how many children there were in total). The family was poor and Jones’s description of the food insecurity helps explain why Hendricks’s lyrics so often touch on food, along the lines of “Women tend to business and cook.” At the same time, his father proffered the lesson that poverty was not about money, it was about the spirit.

Jones’s chronology could be a little clearer but, early on, young John (later changed to Jon) sang in local bars to make money. He listened to songs on jukeboxes; he learned to sing not only the melody, but the other instrumental parts as well (excellent training for the vocalese-to-come). The family was alcohol-free, but it accepted that Hendricks earned money for the household in bars. This seems to me to be an early lesson in straddling the line between the spiritual and, well, call it the worldly.

The family was able to settle for a good while in Toledo, OH, living just a few houses away from the Tatum family. The book relates a story about Mrs. Tatum, who told her almost sightless son Art to learn a piano roll in one day, which he did. Turns out the quick assignment was actually cut by two piano players. Jon would go to the Tatum house and Art, 12 years his elder, played chords that Jon would sing; ear training that was a far cry from the simple solfège lessons he might have had in school. In fact, Hendricks never learned to read music. This isn’t unique in jazz, of course, but when he became a bandleader, it meant that he couldn’t produce written charts and had to teach his musicians by singing their parts to them (which is what Charles Mingus — who was musically literate — also did). As time went on, and Hendricks cycled through a number of rhythm sections and vocal replacements, this limitation caused increasing problems. The difficulty of preparing new musicians for gigs was exacerbated by the fact that Hendricks hated to rehearse; he greatly preferred taking up rehearsal time by telling stories.

Success came to Hendricks early on. Again, the exact timing is not clear here but, in his teens, Hendricks sang on the radio and was the opening act in Toledo’s Waiters and Bellman’s Club, an after-hours black-and-tan club. He consorted, to some degree or other, with the in-house strippers. Clarinetist-performer Ted Lewis, one of the most successful acts of the time, offered him the part of “the black boy” in his “Me and My Shadow” act, but Hendricks’s mother nixed it.

Success came to Hendricks early on. Again, the exact timing is not clear here but, in his teens, Hendricks sang on the radio and was the opening act in Toledo’s Waiters and Bellman’s Club, an after-hours black-and-tan club. He consorted, to some degree or other, with the in-house strippers. Clarinetist-performer Ted Lewis, one of the most successful acts of the time, offered him the part of “the black boy” in his “Me and My Shadow” act, but Hendricks’s mother nixed it.

There’s a break in the narrative when the family moves to Kentucky and Jon stays in Toledo. He fathers a child whom he visits when he’s in town but, besides that, he maintains little contact. Over the course of time, Hendricks was to father six children by three women. For much of his life he had little to do with his kids. His third wife was Judith Dickstein, to whom he stayed married for 56 years. To some degree, because of her intervention, he began to try and bring his children into his life. Several of his children eventually began performing with him, but their time together was fraught.

Hendricks was drafted into the army in 1942 and his experiences for the next two years are horrifying. To learn about these is, in itself, reason enough to read This Is Bop. Suffice it to say that racism was responsible for nearly killing him. His prodigious memory and intelligence were, to a large extent, responsible for his avoiding the worst degree of punishment when he was court-martialed for desertion.

After the war and into the mid-’50s, Hendricks tried to forge a place for himself in jazz. He started a group, Jon Hendricks and His Beboppers, in Rochester, NY, and, despite never having played or studied the drums, moved into the drummer’s chair of that band. Dizzy Gillespie asked Jon to sing in his band, but he refused and Joe Carroll got the gig. He decided to try law school and was accepted at the University of Toledo. When Hendricks graduated, his excellent grades should have qualified him to be appointed the State’s Juvenile Probation Officer, but racism prevented that. His G.I. Bill money had run out, so grad school was out.

After Hendricks had sat in with Charlie Parker, Bird told him to come to New York and look him up. Hendricks’s other life plans fell through so, about a year later, he went to NYC and found Parker who, to Hendricks’s surprise, remembered him well. Bird helped him get some gigs, but the next few years were a scuffle. He had some opportunities to perform as a singer and, with limited success, tried to sell songs he wrote. In describing the scene at the Brill Building, Jones somewhat blithely suggests that it was common for famous songwriters, like Frank Loesser and Irving Berlin, to employ other writers to write songs they would claim as their own. I don’t consider those two guilty of that, although many others were and, as I learned here, Hendricks was guilty throughout his life of trying to claim full authorship rights to songs he had not written — even those that had come with their own original set of lyrics. The biographer includes the complaints of other musicians regarding Hendricks’s attempts to claim credit (including Harry Sweets Edison, who pursued him with a gun), and for underpaying or not paying money due them. I wish the author had come up with more than sketchy information about the relationship of Black songwriters to ASCAP, the major distributor of royalties. At one point Jones claims that they were routinely excluded, but Hendricks himself was granted membership, as were other Black composers.

In the course of events, Hendricks met and worked for and with Dave Lambert, who’d been a jazz singer and arranger since the early ’40s. There are some terrific stories about how Lambert survived the lean times. Then, Annie Ross haphazardly wandered into the picture. Lambert and Ross were both extraordinary musicians, quickly able to learn their parts. Lambert could skillfully boil down big band arrangements into three vocal parts and write arrangements for rhythm sections as well. The stage was set for the helter-skelter creation of the trio’s debut album, Sing a Song of Basie. That 1957 album kicked off the years of the greatest popular success Hendricks would enjoy, from the late ’50s to the early ’60s.

Ross left the group in 1962, and other female vocalists tried to fill her slot. It was not an easy task, although Yolande Bavan did an admirable job. The demise of the group came in 1964, but Hendricks’s career was far from over. He would perform and record for the next 40 years. The biographical motifs set up by Jones continued to play out — the messy relationships with family and other musicians as well as the perennial struggle to “get back on top.” But there are many triumphs along the way: his part on the show “Evolution of the Blues,” working with Duke Ellington on a “Concert of Sacred Music,” extensive touring with several members of his family singing in the group, collaborations with the group Manhattan Transfer, an honorary degree and teaching at the University of Toledo. His final studio recording, 1990’s Freddie Freeloader with George Benson, Al Jarreau, and Bobby McFerrin — the Four Brothers –was one of a kind.

In his music, Hendricks was able to strongly connect with listeners and to inspire other artists. He was a spectacular scat singer — I think the best that jazz has produced — and an incredibly prolific and clever lyricist. He often worked with younger musicians; they were both elated to learn what he had to teach them and, in many cases, not happy about the way Hendricks treated them. My reaction to This Is Bop is similar: I’m glad to have learned about the darker sides of Jon Hendricks, but I will continue to listen to his music with enormous pleasure. The work stands on its own, and will endure.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.

Hendricks never lost his abilities or his wit, but my impression is that his forward progress slowed way down when Dave Lambert left LH&R. Theirs was a sensational combination of talents, and Hendricks never worked with anybody like Lambert again. His later career, good as it was, seemed to be a succession of do-overs. Lambert was the one with the big ideas, all lost with his death in 1966.

Dick-I agree. Their skills meshed in an extraordinary way.

In terms of big ideas, let me note that they squabbled about the “Sings Ellington” record. Hendricks wanted to do ALL the parts, as in “Sing a Song of Basie,” but Lambert didn’t. Hendricks made a crack to Lambert about it “not being in his blood.” Mean-spirited, to say the least. I assume that Columbia records was just as happy not to go through all that over-dubbing. The biographer doesn’t like this record, but I very much do.