Poetry Review: Joshua Bennett’s “Owed” — Paying a Debt, Memorably

By Matt Hanson

Every exquisitely crafted line reflects the pull of a threatening body politic, the gravitational force of history.

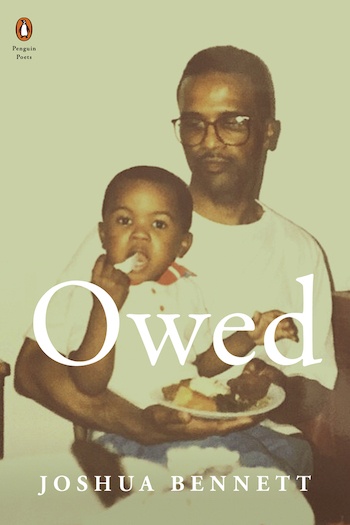

Owed by Joshua Bennett. Penguin Books, 96 pages, $20.

Buy at Bookshop

Poet (and current Boston resident) Joshua Bennett is on a roll. His assured debut The Sobbing School won a National Poetry Prize, establishing the scholar/performer/teacher as one of America’s leading poets. Owed, his second collection, reinforces this rookie preeminence by proffering more of his virtuosic technical skill, subtle wit, and cinematographic eye for vibrant scene-setting.

Poet (and current Boston resident) Joshua Bennett is on a roll. His assured debut The Sobbing School won a National Poetry Prize, establishing the scholar/performer/teacher as one of America’s leading poets. Owed, his second collection, reinforces this rookie preeminence by proffering more of his virtuosic technical skill, subtle wit, and cinematographic eye for vibrant scene-setting.

The titular pun deftly toys with the notion of inheritance, a generational debt. Who owes what to whom? Bennett’s odes explore the emotional, philosophical, and political debts that he owes to the everyday things that helped to create him — the dollar store, his father’s gold chain, the plastic on his grandmother’s couch, the second skin of long johns, the amusingly gritty summer job, the do-rag, which he wittily rechristens “the durag.” He expands on this sense of obligation to the abstract concepts that nurtured his imagination, such as family, race, history, education, politics, and the subversive melody of lyrical poetry.

In “The Book of Mycah,” arguably the best of Bennett’s narrative poems, the random violence inflicted on neighborhood kids who populated his NYC childhood is compressed into a word-driven montage. The titular “son of Marvin of Tallulah” is “maroon-clad from head to foot like an homage to blood…high-top Chuck Taylors, size 12, sounding like ox hooves.” He takes it upon himself to interfere in a street brawl on his cousin’s behalf, only to have policemen’s ammo interrupt, hitting him “mid-stride, lifted his six-foot frame from the ground, legs still pumping.” This agonizing memory is etched via sharp details that accumulate to tell an ugly but all-too-familiar story.

The substance of these masterfully wrought poems aren’t always pretty. Every exquisitely crafted line reflects the pull of a threatening body politic, the gravitational force of history. Nevertheless, there are moments of transcendence, the result of Bennett’s alchemical ability to turn the raw pulp of life into exquisite verse. In multiple poems titled “Reparation” he wittily dissects both the urgency and impossibility of such an action in today’s charged climate. “Monuments to the fallen” are proposed as retribution, along with things like scholarships as well as a call for “scholars that love us/ enough to break this language/ lengthwise, filled as it is/ with the bones of our fallen.” Bennett’s poems suggest what is necessary to begin the work of rejuvenation: establishing and maintaining the “ground/ where the children can play/ & come home whole.”

Early on he learned to use the power of words as a tool for social survival. In “Token Plays The Dozens” he describes how cliché contests featuring swapping “yo’ mama jokes” gave him the first flashes of pride “against a host of boys more beautiful than I & better dressed too.” Ironically, his ability to talk such eloquent shit came from a deeply traumatic source: “the blades between each molar honed at home watching my mother use her most/ luxurious words to pummel the man she loved into powder.”

Poet Joshua Bennett — his latest book examines the nature of inheritance.

Bennett’s family was at the center of his daily struggles to not only survive but thrive. Here’s how he addresses and surmounts stereotypical celebrations of the Black maternal: “So much has been said/ about black men/ & their mothers,/ Almost none of which works for you & me…I am your twin brother/ of a sort, counterfeit currency/ moving through the world/ on your behalf, making things/move.” Bennett’s allegiance to radical honesty, along with bone-deep commitment to the people who raised him, has shaped his unique voice. “We live/ in a country/with no language/ for what you are,/ & I persist/ for the sake/of your glory.” Here what’s owed is written in flesh and blood — there’s a devastatingly understated awe in this ode to Bennett’s inspirations.

In “America Will Be,” the final poem of the collection, Bennett mediates on the story of his father, who grew up in Alabama as one of ten children, “side by side in the kitchen each morning like a pair of hands exalting.” When he asks his father what was the hardest part of going to school during that time and that place, the man doesn’t bother to mention the determination to deal with the attack dogs, Bull Connor’s personal tank, or being stabbed with pens while walking through the halls. Instead, he stoically replies that it was eating lunch in the cafeteria alone. Considering that violent past and it’s chilling resonances today, the present doesn’t necessarily look all that bright: “He looks/ at me like the promise of another cosmos & I never know what to tell him.”

Bennett’s poems don’t shy away from precisely rendering the ugliness of world as it is, but they also know how and when to offer some respite, a moment of grace. After pondering an America that continues to allow the injustices his father grappled with, Owed ends on a powerful note of redemption via a relatively small but enduring observation: “loud as the sound of my father’s/unfettered laughter over cheese eggs & coffee/ his eyes shut tight as armories his fists/ unclenched as if he were invincible.” He’s not, of course. But these poems might well be. And that’s a debt that readers should rejoice that Bennett has been strong enough to repay.

Matt Hanson is a contributing editor at the Arts Fuse whose work has also appeared in American Interest, Baffler, Guardian, Millions, New Yorker, Smart Set, and elsewhere. A longtime resident of Boston, he now lives in New Orleans.