Book Review: “Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong” — The King of All Kings

By Michael Ullman

He may be extreme as a polemicist, but Ricky Riccardi shines when he sticks to jazz’s history.

Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong by Ricky Riccardi. Oxford University Press, 432 pages, $34.95.

This book examines the neglected mid-years of Louis Armstrong’s unparalleled career, the “big band years,” which began in the late ’20s and ended when Armstrong put together his All Star band soon after WWII. Author Ricky Riccardi has an argument about this period: he wants to demonstrate that Armstrong was never more influential, or popular, than when recording and performing with a big band. Yet he was simultaneously “vilified” by jazz fans and the jazz press.

This book examines the neglected mid-years of Louis Armstrong’s unparalleled career, the “big band years,” which began in the late ’20s and ended when Armstrong put together his All Star band soon after WWII. Author Ricky Riccardi has an argument about this period: he wants to demonstrate that Armstrong was never more influential, or popular, than when recording and performing with a big band. Yet he was simultaneously “vilified” by jazz fans and the jazz press.

This is a difficult contention to prove. Riccardi describes Armstrong as “a man seemingly vilified by the Black press,” but then uses articles from the Black press to underline the durability of the trumpeter’s popularity. In 1935, after a year and a half in Europe, Armstrong appeared at the Apollo. It’s there that Heart of Rhythm begins. It was a crucial engagement: the trumpeter hadn’t recorded in the United States for several years. As Riccardi notes, he opened his performances by playing “Ain’t Misbehavin'” to record crowds. The New York Amsterdam News proclaimed at the time that Armstrong was “at the peak of his career.” A decade later he was still performing to record crowds at the Apollo. The author asserts that “Louis Armstrong is synonymous with jazz” and, again, that “jazz is synonymous with Armstrong.” Yet he still insists that Armstrong “ultimately transcended the world of jazz — and for that, the jazz world never forgave him.”

Who is this jazz world? Certainly not musicians. Riccardi quotes Bill Coleman, who heard Armstrong at the Savoy Theater in 1929: “His fingers seemed to be flying over the valves and the things that were coming out of his horn were things that I had never heard from any trumpet player before and that’s when I realized that Armstrong was the king of all kings of jazz.” Decades later, Miles Davis famously said you couldn’t play anything on trumpet that Armstrong hadn’t already played. The literature, including Riccardi’s book, is filled with tributes from jazz musicians to Armstrong as a singer, trumpet player, and entertainer. Nor did audiences turn on him. I was thrilled to have heard him play in tents on Boston’s North Shore, in Symphony Hall, and in a dance hall at Hampton Beach. The listeners, jazz fans all, were ecstatic.

In order to sustain his contradictory argument, Riccardi has to draw a vague distinction between jazz fans and “the general public.” The divide is difficult to discern. In a weird — and to me unconvincing — way, the jazz world sometimes becomes the enemy for Riccardi. He describes Armstrong’s successes in California at the beginning of the ’30s, when he was a star appearing in a band that also featured drummer and vibist Lionel Hampton and trombonist Lawrence Brown, the latter soon to begin a lifelong stint with Duke Ellington. Always thorough, Riccardi quotes Hampton and others praising Armstrong to the skies. His influence continued to snowball. According to Riccardi, Coleman, Count Basie, and even Dizzy Gillespie mimicked phrases from Armstrong’s recording “I’m a Ding Dong Daddy from Dumas.” Armstrong spread the word — he broadcast a 15-minute version of the song, improvising all the way.

“To those who lived through it, there seemed to be a consensus that this was truly Armstrong’s greatest period,” the author contends. He notes that Ellington’s band listened to Armstrong’s broadcasts every night. Yet he also insists, after describing the wild response at Sebastian’s Cotton Club to songs like “St. Louis Blues” and “Black and Blue,” that “This was not the jazz world; this was the world of Black show business.” The two worlds were pretty compatible at the time: if Armstrong and people like Ellington, who was appearing at Harlem’s Cotton Club, weren’t jazz, who was?

Later, the “jazz world,” according to Riccardi, is said to have become openly hostile. “It was the jazz world,” he observes, “that put pressure on Armstrong to break up the big band and form a small group…and then ditched him when the small group didn’t reflect the latest trends.” This jazz world has a lot to answer for: bands led by Basie and others also faded away in the postwar years. Economics was the villain. A Time Magazine article set the record straight in the winter of 1946: “The big brassy jazz bands had become a luxury that people were unwilling to pay for…. In the past eight weeks, Benny Goodman, Tommy Dorsey, Harry James, Les Brown and Jack Teagarden decided to disband. Gene Krupa and Jimmy Dorsey cut salaries. This week Woody Herman gave up too.” Armstrong was lucky: via the All Stars he had come up with an attractive alternative that performed a ready-made repertoire of New Orleans classics and pop tunes, standards, and novelty numbers he had absorbed and transformed over the preceding decades.

Not that Armstrong was above criticism, even as an entertainer. I wonder if I would have been among the naysayers. Riccardi describes, apparently admiringly, performances in which Armstrong would take an innocent number and prolong it by playing as many as 400 high C’s in a row (as somebody or other counted). Riccardi admits the musician was busy destroying his lip. Did those displays make any sense musically? He might as well have been doing push-ups. Some skeptics pointed out the dull as dishwater sameness of some of Armstrong’s big band arrangements, although those arrangements had been created to showcase his playing and singing. It’s a bit like criticizing how a diamond is set — but I can see the charge. None of these reservations undercut the performances of genius during this period, on pieces like “Star Dust,” “When You’re Smiling,” “Between the Devil and the Deep Blue Sea,” and then there are delightfully entertaining numbers such as “You Rascal You.” (These are on Louis Armstrong: The Complete Decca Studio Master Takes, 1935-1939.) I’m a lifelong fan of the two-sided version of “Sunny Side of the Street.” Every critic I know agrees on these highlights.

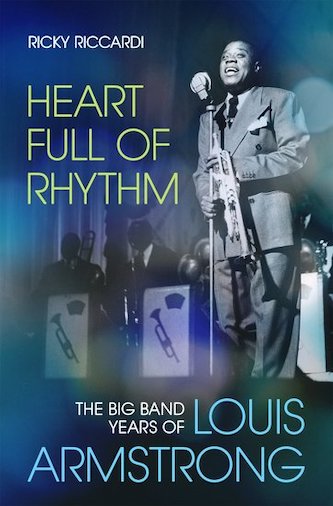

A 1929 Louis Armstrong publicity shot. Photo: The Lil Hardin Armstrong-Chris Albertson Collection, Louis Armstrong House Museum.

He may be extreme as a polemicist, but Riccardi shines when he sticks to jazz’s history. Heart Full of Rhythm is full of absorbing new material and revealing details, including a number of uncensored comments from Armstrong himself. Near the book’s beginning, the author describes the mixed race session that produced “Knockin’ a Jug.” The recording is a masterpiece, thanks to solos by Armstrong and trombonist Teagarden, but the session was cut short because of the band’s heavy drinking. It’s wonderful to learn, though, that during the session Armstrong climbed up a stepladder to better hear Teagarden’s sound. We also learn that it took an entire session to record another classic, “I Can’t Give You Anything But Love,” because of the perfectionism of the producer. (The 1929 big band sides, as well as the immortal Hot Five and Seven recordings, are expertly remastered by John R.T. Davies on the four-disc set Louis Armstrong: Hot Fives and Sevens on JSP Records. The label has also released Louis Armstrong: The Big Band Recordings, 1930-1932.)

Already a star in 1929, Armstrong was still an African American in a racist country. He was also an enormously popular musician internationally at a time when live entertainment, especially jazz, was often dominated by underworld types. He was, as Riccardi documents, on occasion pressured to do gigs. Because of overwork his lips were repeatedly left in tatters, which put his career on hold. There were a variety of indignities. The volume includes some telling photographs. In one, “a joyous Armstrong” takes a bow “during his record-setting engagement at the Paramount Theatre in April, 1937.” Another is of the band, forced to urinate outside of their bus. Armstrong was called the “Answer to Theater Owner’s Prayer” but Riccardi documents his struggles with managers in the United States (many with gangster ties) and abroad with new, and sometimes stunning, evidence. Eventually, Armstrong ended up with what turned out to be a permanent and satisfying relationship with a man named Joe Glaser. The book provides fresh (at least to me) information about Glaser, including that he was repeatedly charged with rape before he took over, much to Armstrong’s relief, the trumpeter’s career. Once you learn about Glaser’s predecessor, John Collins, who signed both his and Armstrong’s name to various contracts even after the trumpeter tried to dump him, you’ll see why Armstrong was so relieved.

Throughout the big band years, Armstrong kept his poise, even when he was threatened at gunpoint by gangsters who had become impatient with lawsuits. Anyone reading this book will come away with a deeper understanding of the virulence of racism in the “business” of jazz and entertainment during this period. Most important, Heart of Rhythm testifies to the resilience and seriousness of the man himself. In 1933, Armstrong was asked about the origins of his music while he was in Sweden. He saved the newspaper clipping with his lengthy response:

Us negros have created jazz. White musicians have followed us, but they haven’t reached us yet and I think they never will. Because this music is namely an expression for something that lives within us and that white men never fully will understand. The liberation from slavery explains how the jazz was born. The negro has created two kinds of music. First there are these melancholic spirituals, the folk songs from the time of slavery. And now jazz, which is a reaction, because now we dare to laugh and smile—we got human dignity.

Responding Arts Fuse commentary: Louis Armstrong as Negotiator.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: Heart Full of Rhythm: The Big Band Years of Louis Armstrong, Louis Armstrong

This does not address the question of whether aficionados felt Armstrong was being left behind by the development of beebop at the end of this period, without necessarily denying his greatness. Also, the big band sound was probably seen as a dilution of the energies and ethnic intensity of 20s Jazz. But what do I know, I like his semi Jazz records with Ella Fitzgerald (and wonderful back up) in the mid 50s. Perhaps the musical excitement is not there, but still glorious song making and his unfailing expressiveness.

Read Mr. Riccardi’s 20,000+ word response here:

https://dippermouth.blogspot.com/2020/10/hooey-about-louis-jazz-world-vs-louis_7.html