Jazz Album Reviews: Mesmerized By Vinyl — Newvelle, Louis Armstrong, and Stan Getz

By Michael Ullman

Playing vinyl involves holding something in your hand, putting a needle down and, at least on my high end system, listening to sound quality that can mesmerize.

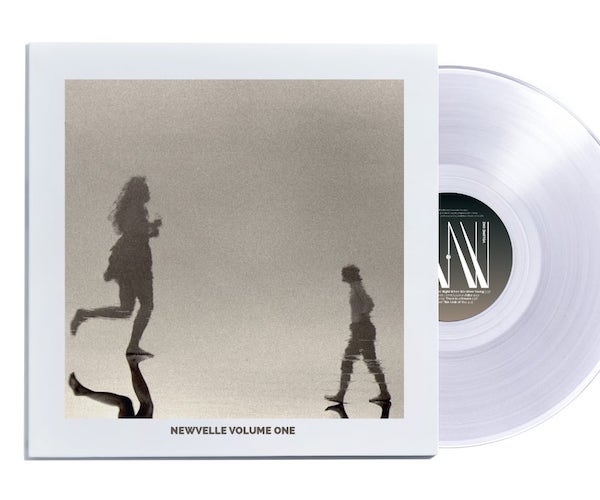

Newvelle Volume One. Newvelle Records 633019

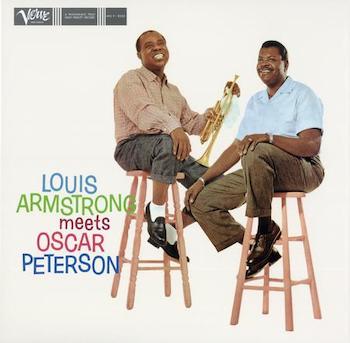

Louis Armstrong Meets Oscar Peterson, Verve MG V-8322 (Acoustic Sounds)

Getz/Gilberto, Verve 8545 (Acoustic Sounds)

Industry people are writing that sales of vinyl records, such as the three distinguished examples of lps listed here, have surpassed the sales of compact discs. Of course, that’s because the sales of cds are sagging so desperately, though it is still interesting to speculate why. I know the magic of lps. I bought my first, Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy, in the ’50s when I was 13. It seemed miraculous. I had listened to music on the radio and been to hear music at Symphony Hall. But this experience was something else. My hand shook as I put the needle down on the record: though it seems obvious today, what struck me was that I could play anything I liked over and over again. But why search out expensive lps in a digital era? I know audiophiles who have replaced their modern high end systems with Garrard turntables and Marantz amplifiers from a half century ago. (I say that they are looking for authentically bad sound.) Still, for most people, it couldn’t merely be nostalgia that is driving the market for vinyl.

In his notes to the Newvelle anthology listed here, Elan Mehler, the label’s producer, attempts to solve the mystery. Like many audiophiles, including me, he believes that the sound on a high end lp is (generally) “warmer, bigger, more present” than what is found on digital recordings. He goes further. “Today, music is everywhere,” he insists, comparing it to a flood. Being everywhere, he adds, “the music also seems to be nowhere.” To Mehler, vinyl is “a return to the real.” Playing vinyl involves holding something in your hand, putting a needle down and, at least on my high end system, listening to sound quality that can mesmerize. It helps that on the best recordings the musicians seem to be preternaturally present.

Via Newvelle Records, Mehler has been issuing exquisitely produced lps in groups of six and selling them in “seasons.” I’ve reviewed, often ecstatically, several of those seasons on this site. (I have all but season two.) It’s not just the sound that is distinguished. Mehler has an ear for the best jazz out there performed by musicians both famous and relatively, undeservedly, obscure. He also has the courage and foresight to record projects such as duets with bassist Rufus Reid and Sullivan Fortner and a solo piano record by drummer Jack DeJohnette. He has the ubiquitous Dave Douglas recording haiku, and guitarist Bill Frisell appearing as a sideman with Gregory Tardy. He has also recorded musicians I had not previously heard of — I have learned to trust his taste and commitment. Newvelle Volume One offers eight numbers from various label sessions, including two previously unreleased numbers. The album begins with a gorgeously restrained version of the ballad “Last Night When We Were Young” led by pianist Frank Kimbrough. Almost the first sounds we hear, focused and sensitive, come from Andy Zimmerman’s tenor saxophone. Next, the mood changes totally when guitarist Lionel Loueke is heard in a lively duet, “Aziza,” with pianist Kevin Hays. It’s a two-person carnival. With tenor Ted Nash and guitarist Steve Cardenas, bassist Ben Allison recreates and modernizes Jimmy Guiffre’s trio number, “Pony Express.” This is chamber music at its best. For Newvelle addicts, the anthology’s highlights are pianist Don Friedman’s previously unreleased “If I Should Lose You” and Steve Cardenas’ “There in a Dream,” which begins with Thomas Morgan’s richly rendered bass solo: the sound is detailed as well as warm. I’ve heard Morgan from a few feet away. This is the way he sounds up front, and it’s worth the price of admission.

The two Verve records listed here have been reissued on heavy weight, crystal clear lps by Chad Kassem’s Acoustic Sounds as mastered by Ryan Smith. The 1959 session Louis Armstrong Meets Oscar Peterson is a result of Verve founder Norman Granz’s desire to bring together musicians from different backgrounds. (He produced the Jazz at the Philharmonic jam sessions.) Oscar Peterson, he believed, could fit in anywhere. Although this lp isn’t my favorite Armstrong from the period, Granz (whose name in the original notes is misspelled “Grans) makes his point. The twelve ballads recorded here include numbers Armstrong had never previously recorded. The emphasis is on Armstrong’s vocals. When he takes a trumpet solo, he sounds almost polite, as if unwilling to burst the bubble of the recording studio. Peterson is garrulous as usual, but doesn’t offer the kind of robust counterweight Armstrong is used to with his All Stars. There are no blues, but the songs are top notch. The record begins with “That Old Feeling.” When Armstrong starts to sing, all is forgiven. He is just there, startlingly present. He’s my favorite male jazz singer: I even like the way he clears his throat on “Let’s Fall in Love.”

The two Verve records listed here have been reissued on heavy weight, crystal clear lps by Chad Kassem’s Acoustic Sounds as mastered by Ryan Smith. The 1959 session Louis Armstrong Meets Oscar Peterson is a result of Verve founder Norman Granz’s desire to bring together musicians from different backgrounds. (He produced the Jazz at the Philharmonic jam sessions.) Oscar Peterson, he believed, could fit in anywhere. Although this lp isn’t my favorite Armstrong from the period, Granz (whose name in the original notes is misspelled “Grans) makes his point. The twelve ballads recorded here include numbers Armstrong had never previously recorded. The emphasis is on Armstrong’s vocals. When he takes a trumpet solo, he sounds almost polite, as if unwilling to burst the bubble of the recording studio. Peterson is garrulous as usual, but doesn’t offer the kind of robust counterweight Armstrong is used to with his All Stars. There are no blues, but the songs are top notch. The record begins with “That Old Feeling.” When Armstrong starts to sing, all is forgiven. He is just there, startlingly present. He’s my favorite male jazz singer: I even like the way he clears his throat on “Let’s Fall in Love.”

Deservedly, Getz/Gilberto is one of modern jazz’s most famous recordings. Recorded in March, 1963, it opens with “The Girl from Ipanema” and includes “Desafinado” and “Corcovado.” The disc rapidly became the favorite jazz album of sophisticated college students everywhere, and others as well. (It was recorded in two sessions. I believe the mic setups were changed between March 18, the date of the first session, and March 19.) The Acoustic Sounds lp under review isn’t the first audiophile lp reissue. I have a 200 gram lp version of Getz/Gilberto from Mobile Fidelity. To me, there are subtle differences. Listening to “The Girl from Ipanema,” I hear a slightly more focused, precise sound on the new Acoustic Sounds lp. The stereo separation is a bit extreme, as it was on the original: I would have changed that. Familiar though it is, and successful though it was, the music remains marvelous. It’s wonderful to relive the heft and forthright mastery we hear on Getz’s solos throughout. His entrance on “The Girl From Ipanema” transforms the stage: that’s something I wouldn’t change. In his original notes, lyricist Gene Lees praises specifically the sound of Getz/Gilberto: “No recording I’ve heard captures his sound as well as this one, just as no previous recording has captured João’s sound like this. Part of the reason is that the recording was made at a tape speed of 30 inches per-second, instead of the usual 15.” Now that sound is clearer, more vivid and at the same time more natural than ever before.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for the Atlantic Monthly, New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, Boston Phoenix, Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.

Tagged: Acoustic Sounds, Getz/Gilberto, Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy