Jazz Remembrance: The Lasting, Complex Legacy of John Coltrane

By Steve Provizer

Of all the musicians who were harbingers of change, none has had the long-term influence on young musicians that John Coltrane has had.

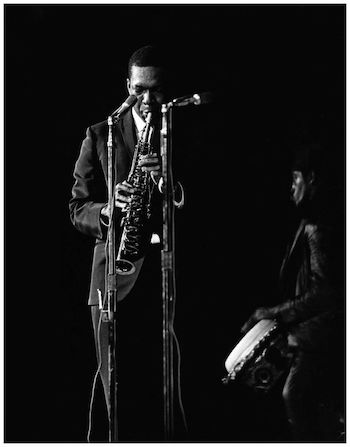

John Coltrane at Stanford University, January 1966.

Photo: Andy Nozaka.

Today is the birthday of John Coltrane (born September 23, 1926). By consensus, Coltrane was one of the most important musicians in jazz history. His playing has profoundly moved me and I know this feeling is shared by many others. In its day, his music catalyzed a fracture in jazz — a fracture that persists — while his music has continued to move more and more deeply into the DNA of jazz.

As I note in my piece on Ornette Coleman, one highly contentious step in the evolution of jazz had been the arrival of bebop in the early ’40s. But, an even more disruptive movement began to take shape in the ’50’s, chiefly through the work of Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Albert Ayler, Sun Ra, and Eric Dolphy. This growth was before — and in some ways laid the groundwork for — Coltrane’s triumphs in the early ’60s. But, for several reasons, Coltrane was most responsible for the intensity and duration of this creative shakeup.

There’s an expression in jazz: “You gotta be able to go inside the house before you can go outside.” Meaning, before you play “free” — without harmonic or other formal strictures — you need to know how to play chord changes and the blues. Of all the musicians responsible for the dramatic changes that led up to “free jazz” or the “New Thing,” Coltrane was the only one who had successfully operated on both sides of the house. Through his work with Miles Davis and with his own groups, he had established himself during the ’50s as an important mainstream improviser; an “inside” player par excellence. Dolphy, for all his boundary stretching, stayed basically inside. Taylor never established himself as a straight-ahead player and Ayler remained “outside.”

To further confuse things, while Coltrane was shattering boundaries and seeking more and more freedom from traditional jazz moorings, he continued to make melodic music: the Johnny Hartman and Ellington records, recording “Someday My Prince Will Come” with Miles. He was inside as late as 1964’s album Crescent.

In the ’50s, Coltrane had gone through periodic changes in his approach, but none — even the “sheets of sound” –were that radical. Many listeners who followed Coltrane through these changes found themselves struggling to understand his tumultuous new path but, because of the credibility that he’d built up, they could not dismiss it. Coltrane lent gravitas to the new music. Because of him, people couldn’t say musicians were playing “free” because it was all they could do. They were choosing to play it. This effect, it should be noted, was strongest during Coltrane’s life and has faded with time. In other words, each new musician who comes up is, to some extent, still subject to the scrutiny of his or her technical credentials.

In addition, Coltrane reinforced and deepened a strain of spirituality that became identified with the freedom he sought in the music. The secular, outlaw-tinged legacy of jazz, along with perceptions of the widespread use of hard drugs, meant it had a tenuous moral standing in the culture at large. Coltrane changed that. He talked about trying to be in tune with the Creator, but never proselytized, never tried to elevate his status as a “spiritual” person. Still, his deep dedication to the music, obvious popular success (the album A Love Supreme), and getting off drugs reinforced his image as an exemplary person. And that made him the leader — even if an involuntary one — of this shift in perception toward the music.

Of all the musicians who were harbingers of change, none has had the long-term influence on young musicians that Coltrane has had. Because of him, radical departures from jazz norms has been a viable choice — a choice, to a large extent — that has been yoked directly to his investment in spirituality. Coltrane’s integrity — as man and musician — created the space for the durability of his legacy. And that heritage has set up the fundamental possibilities generations of young musicians have had to grapple with before they decide which direction they want to take. In fact, whether the decision is consciously made or not, it’s hard to hear a jazz tenor saxophonist and not hear the shadow of Coltrane in there somewhere.

Steve Provizer writes on a range of subjects, most often the arts. He is a musician and blogs about jazz here.