Arts Remembrance: Flutist Doriot Anthony Dwyer

By Robert Israel

Doriot Anthony Dwyer was a virtuoso flutist, one who could coax brightly burnished tones out of the instrument.

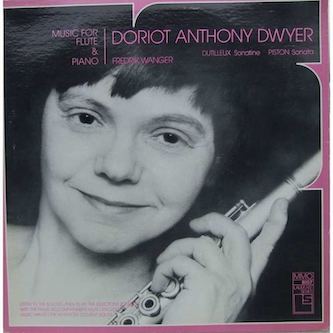

The late flautist Doriot Anthony Dwyer. Photo: Lincoln Center.

Time magazine recently published 100 Women of the Year, a feature devoted to highlighting a century of accomplishments by women in politics, the arts, and medicine. Several women the sage editors considered to be musical trailblazers were listed: Madonna, Pussy Riot, Aretha Franklin, and Sinead O’Connor. An inevitable part of the profiles was testimony to the struggles these artists faced trying to achieve fame in a male-dominated field.

And while it’s true these female musicians made lasting impressions, there was one glaring omission: the achievements of flutist Doriot Anthony Dwyer, who died on March 14, 2020 at the age of 98.

Dwyer was not as flamboyant or as brash as the others on Time’s list. She did not seek attention in the press. Yet, like those on the roll call in Time, she broke into a male-dominated music field through a mastery of her instrument.

Born in Illinois and schooled in music as a youngster, she was grandniece to Susan B. Anthony, the social reformer and women’s rights activist. As a young adult, she played freelance (appearing with Frank Sinatra and later joining the National Symphony Orchestra). Dwyer was 30 years old when she auditioned for the Boston Symphony Orchestra at Tanglewood. Maestro Charles Munch — unimpressed with male candidates — proposed a “ladies day” in 1952, in which Dwyer and one other female soloist were invited to try out. At the time, Dwyer was performing with the Los Angeles Philharmonic. She traveled to Lenox, financing the trip herself, telling her employers in Los Angeles she needed “elective surgery.” The audition was grueling — it lasted several hours. When it was over, Dwyer returned to California, convinced she did not get the gig. Soon afterward, she was summoned back to Lenox, but she told the BSO she was unable to return. She was convinced, she told an interviewer many years later, that the job would go to a male flutist anyway.

The BSO surprised her with an offer; she requested a higher salary than the one she was making in Los Angeles. She retained the position here for almost four decades (1952-1990). Only one other woman achieved a similar feat: Helen Kotas of the Chicago Symphony, who held a principal chair at a major American orchestra from 1941 to 1948.

I heard Dwyer perform numerous times at Symphony Hall during the ’70s and ’80s, but came to appreciate her unique talents most after I attended the BSO Chamber Players concerts at Jordan Hall. Because of the venue’s smaller size, concertgoers are given opportunities to hear, close up, the warmth and expanse of a performer’s talents.

Listening to Dwyer during these concerts made it clear that she was a virtuoso flutist, one who could coax brightly burnished tones out of the instrument. She did not display the whimsy of, say, Sir James Galway, who often appears wearing a multicolored cummerbund about his waist and who uses his playful spirit to prance onstage, punctuating the notes with body language that adds drama and playfulness. In contrast, Dwyer sat on stage without calling attention to herself, yet she was quietly exhilarating, memorable in that she left me pondering her performances long after I had exited the hall.

For those unfamiliar with Dwyer’s sound, I would send you to her rendition of a piece composed for solo flute by Claude Debussy in 1913. Titled “Syrinx,” it refers to the part of a bird’s thorax that produces birdsong. You can listen to it here on YouTube. You may hear similarities to Debussy’s “Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun,” which was composed in 1894. That is because “Syrinx” calls upon the flutist to conjure up the same mesmerizing, haunting tones, sounds that soar and then land earthward without ever seeming to touch the ground. Dwyer was one of those rare musical spirits who are able to perform music that jazz musician Eric Dolphy (a saxophonist and flutist) called “vanishing”: “Music, after it’s over, it’s gone, in the air, you can never capture it again.”

For those unfamiliar with Dwyer’s sound, I would send you to her rendition of a piece composed for solo flute by Claude Debussy in 1913. Titled “Syrinx,” it refers to the part of a bird’s thorax that produces birdsong. You can listen to it here on YouTube. You may hear similarities to Debussy’s “Prelude to the Afternoon of a Faun,” which was composed in 1894. That is because “Syrinx” calls upon the flutist to conjure up the same mesmerizing, haunting tones, sounds that soar and then land earthward without ever seeming to touch the ground. Dwyer was one of those rare musical spirits who are able to perform music that jazz musician Eric Dolphy (a saxophonist and flutist) called “vanishing”: “Music, after it’s over, it’s gone, in the air, you can never capture it again.”

Dwyer did not entirely avoid politics. She was present at the ceremony on October 17, 1978, when Susan B. Anthony’s likeness was unveiled on the new dollar coin. In an interview with the New York Times, she asked about the significance of her being one of the only women to have been hired for a chair at the BSO. Her response: “This has changed, but it could change even more. I think it will.”

Times have not changed all that quickly. This point was recently made by the travails of Elizabeth Rowe, the current principal flutist at the BSO. Alerted to wage disparities between men and women musicians in the orchestra, Rowe initially complained to the BSO management. After garnering support from her fellow musicians, she felt compelled to sue the orchestra. She eventually received the same rate of pay as her male counterparts. That celebrated case – she is now paid over $250,000 a year – was widely reported in the press.

Reflecting on the long life and career of Doriot Anthony Dwyer, I want to pay grateful homage and respect not only to her pioneering accomplishments as a musician and teacher, but also to her bewitching rendition of Debussy’s “Syrinx.” It is spring now — a very troubled spring. But there are moments when the lyrical, cleansing sound of Dwyer’s flute comes to me — at dawn and at sunset — and her birdsong pushes aside the threatening cacophony.

Robert Israel, a contributing Arts Fuse writer since 2013, can be reached at risrael_97@yahoo.com.