Poetry Review: Richard J. Fein’s “Whitman/Vitman” — A Vigorous Homage

By Susan de Sola Rodstein

It’s hard to think of a contemporary poet who has engaged so passionately and devotedly, over many decades, with a single forebear.

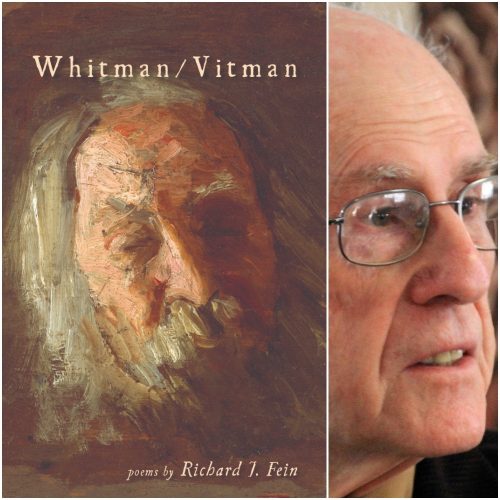

Whitman/Vitman by Richard J. Fein. (Finishing Line Press)

Richard Fein’s latest publication, a chapbook from Finishing Line Press, is titled Whitman/Vitman. While this seems to chime as kind of Jewish joke, Fein’s engagement with Whitman is deeply serious and has shaped his entire vocation as a poet. Just as Whitman continued to revise Leaves of Grass until the end of his life, Fein has, over the years, revised his relationship to Whitman, who seems to be never far from his consciousness. This is a slender book, numbering only 14 poems, the last four of which are new. The other 10 have appeared in some of Fein’s 13 books of poems and translations. A note in the front matter tells us that the bi-centennial of Whitman’s birth prompted this gathering of his Whitman-themed poems. Fein’s poetry and his relationship to Whitman have been analyzed by this reviewer in a longer Arts Fuse essay about his poetry collection B’KLYN and his book of essays, Yiddish Genesis, in The Arts Fuse. In that piece, I looked in detail at Fein’s relationship to Brooklyn, a hometown he shares with Whitman, and at his relationship to Yiddish, the lost “mother tongue” of which he has become an accomplished translator.

There is a compelling parallel in the absolute primacy of Whitman’s influence on Fein’s development as a poet and Whitman’s centrality in the development of American poetry — his potency as a force for liberation, both for Fein personally and for American verse. Whitman, despite his limited actual travel, has often been admired as a poet of the vast and untamed America, and of the specific colloquialisms of its boatmen and workers, but he is also very much a poet of New York. The poems gathered here raise intriguing questions about what Whitman might have meant to first and second generation Jewish immigrants. Here is the shortest poem in the book, Fein’s touching translation of B. Alkvit-Blum’s “Your Grass”:

I think of your grass, Whitman,

and hear the stir of the great

stone forest Manhattan.

Fein’s embrace of Whitmanian first-person, free-flowing ruminations is intrinsic to his own poems, and to his translations of Yiddish homages, including H. Leivick’’s sprawling “To America”: “to be a land of milk and honey…O, let the dream of Walt Whitman and of Lincoln also be your dream.” This is, in part, the idealized Walt Whitman, who has come to represent a tolerance and egalitarianism he did not completely possess personally. Consider, then, Fein’s “translation” of an excerpt by an imagined dead precursor, Yankov Rivlin: “Wait, I too bisect V-shaped Manhattan.” This poem shows the Fein hallmarks of intimacy with Whitman, born of long reading, study, and translation. But it ends on a darker note: “Walt, the dark grass will line my throat and mouth.”

There is a sense of continued wonder at Whitman, but the poems are haunted by the impossibility of grasping him fully. They express a sense of frustration, inhabiting the interstices between what the poet wrote and who we imagine him to have been. There are third person descriptions and first person monologues addressed to a frustratingly (and necessarily) silent interlocutor (Whitman). Many of the poems make recourse to the language of the body, and the metaphors (tongues and breath) of the intimate act of translation. In the touching poem, “A Professor Re-reading Calamus (1967),” Fein wonders at his youthful, naïve readings, and, courageously, admits the magnitude of all he missed, and all that he possibly projected: “How could I have taken so long to understand you, Walt?…Forgive my conversions of you…the evasions in my teaching, my book, my life…” It ends: “So, you even misled me, as I misled myself, as you misled yourself/ we two old men ready to accompany each other, to walk the/shoreline, where the last bubbles of spume reach our insteps.”

Although many of the poems in this collection, appropriately, show a Whitmanian looseness and reliance on anaphora, repetition, and cadence, not all the passages here are equally accomplished — some parts are too loose and repetitive for this reader’s taste. Fein often excels in tight forms, and his poetry becomes satisfyingly dense and sonically richer when he directs his attention to detail, as in the dream poem, “Whitman at Timber Creek”:

Something’s hidden in the barks of trees,

within the black sockets of the birches,

within the gnarls, the burls, the knots,

behind the fringed scabs of lichen,

in the wedges of the fungi—

One might say that in these shorter lines, Fein becomes less Whitmanian, although Whitman also drops rich images into his poems without necessarily making them into metaphors or symbols. It’s hard to think of a contemporary poet who has engaged so passionately and devotedly, over many decades, with a single forebear. Whitman/Vitman is more than a random collection — the poems are turning points and crossroads in a kind of double narrative.

In the final, titular poem, “Whitman/Vitman,” Fein, with characteristic humor, imagines Walt Whitman as “Velvl Vitman,” and assures him he would have translated his Yiddish into English. The poem ends with a characteristic second-generation-American specter: imagining who one would be if one had been born one generation earlier:

Or if I was Ruvn-Yankev Fayn, and you still

Walt Whitman, I’d have turned your English

into Yiddish, showing how the body

of a poem could turn into another body,

the two of us closer than ever,

the way V inheres in W.

Susan de Sola Rodstein is a poet and critic. Her collection Frozen Charlotte: Poems was recently published by Able Muse Press. www.susandesola.com

Tagged: Finishing Line Press, Poetry, Richard-J.-Fein, Walt Whitman