Film Review: “63 Up” and the Wonders of Existence

By Neil Giordano

“We know what we are, but know not what we may be.” –- Hamlet

63 Up, directed by Michael Apted, screening at Kendall Square Cinema through December 20.

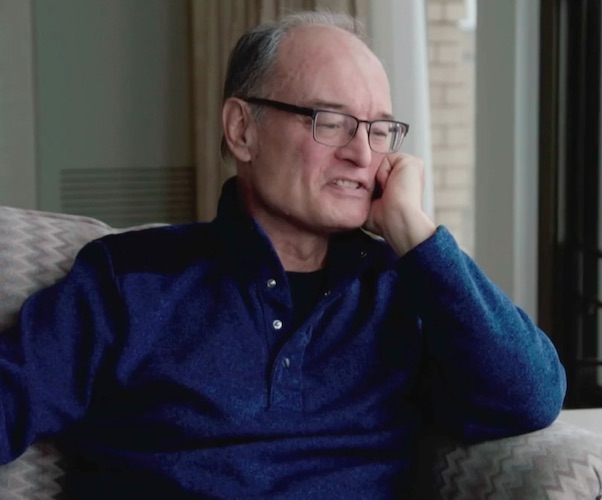

Nick in “63 Up.”

Of the many wonders of the Up series is the powerful way that the documentaries make you conscious of the passage of time, the inexorable passing of each seven-year interval. First, you ask yourself, has it just been seven years since the last Up film? And then you reflect on what has happened in your life since then: births, deaths, marriages, divorces, job changes, friends lost and found. Joyful, yes, and also melancholy, and finally, terrifying. You realize that seven years pass quite quickly, fleetingly even. And suddenly you find yourself contemplating all that has been lost, at what seems to be an accelerating rate. But you calm down once you remember that the film’s subjects, and their reflections on aging, will guide you through your fears and trepidations. They are your old friends — and you listen.

63 Up, the ninth iteration of the series since 1964’s Seven Up, continues the setup’s existential loop-the-loop. And this latest installment bears gifts well beyond its generating plenty of personal reflection. The Up series prides itself on the kind of time-lapse magic only the best longitudinal documentaries provide — and this series is undoubtedly the greatest of all time in that regard.

The cast of subjects have become so familiar to fans of the series that we look forward to checking in on our favorites, whether it be “cheeky chappie” Tony, lugubrious Jackie, posh but likeable attorney John, posh but less likeable attorney Andrew, or farmboy-turned-physicist Nick. 63 Up may, in fact, be the strongest episode of the series to come along in quite some time: we’ve passed the doldrums of middle age and moved into the near-retirement years. And though a new glossary of contemporary terms has crept into the discourse since 56 Up — Brexit, Uber, Trump — Tony and company’s commentary is more introspective than ever. Many are looking forward to ending their working lives: enjoying grandchildren, traveling internationally, savoring the autumn of their lives as best they can. Yet, inevitably, intimations of mortality bob up and down in the conversations. Parents have passed away, many of the subjects still grieving the loss. In addition, many struggle with their own health issues and are grappling with “what’s coming.” Nick’s throat cancer has left him petrified, while one of the most outspoken subjects in the series has passed on. There are losses that we knew would occur if the series continued on for so many years.

Tony in “63 Up.”

Elsewhere, interviews revisit the original purpose of the Up series — to investigate the rigidity of the British class system. The answers are more forthrightly upfront than ever. Andrew, one of the posh Cambridge-educated lawyers, looks back at his career. He has retired comfortably and insists that he had to “work for it” — we can all sympathize. But maybe Andrew himself is not quite the point anymore. We see his children, and his children’s children, living much the same life he did — a world filled with choices, supported by smooth transitions: a straight line from youth to adulthood. He somewhat smugly asserts that “achievement” is clearly more important than whatever social class you were born into. Such conservative observations are not confined to the upper classes. Jackie, with her Cockney accent, seems to agree, concluding optimistically that “children need to know they are capable of doing anything.” Of course, her own life story appears to illustrate a different reality.

As a counterpoint, working-class cab driver Tony continues to work and overcome obstacles to his own economic security. After a lifetime of proud, honest work he laments how ride-sharing services have undercut his regular earnings. Tony’s children, too, show how the bumps in the road are not so easily avoided. One child (now in her 40s) is still struggling to land on her feet. Others in the middle and working classes lament the decline in the National Health Service and other decay in the British safety net. East-Ender Sue, who credits council (public) housing as “chang[ing] her life,” worries that she and her children might be the last generation to enjoy those benefits. Nick, who has long since left England for a professorship in the United States, still feels like an outsider given his rural background. He contemplates the political system’s decisive role in social class mobility, noting that Theresa May was in his class at Oxford, and realizes that only “people from the right public schools” will ever be in power.

Most rewarding, at this point director Michael Apted has himself become as much a part of the series as his subjects, though still in the form of his inquisitive, but reassuring, off-camera voice. Having committed himself to this film for 56 years, he seems as curious as ever, and at 78 — a full two Ups older than his subjects — he manages to maintain his distance during interviews despite having a clear investment, now both professional and personal, in their replies. Indeed, his own biases as a documentary filmmaker are now part of the film itself. In fact, some of the subjects let him have it for his past missteps and assumptions. Jackie won’t let him forget the sexism implied in his questions — to the girls only — about marriage and having children. Tony, in good humor but perhaps with a long-held chip on his shoulder, points out that years ago Apted assumed that he would end up in prison. Their honesty never amounts to an uprising. Apted uses this discontent to add new texture to the series — it is proof that the subjects’ self-awareness has reached a new stage of maturity and self-assurance.

One senses that 63 Up is a final chapter (there’s no word yet on 70 Up). In truth, many of the subjects are only too glad to round out their stories. “Life doesn’t turn out the way you expect,” says Nick at one point. If there were a simpler way to summarize the Up series, I haven’t found one.

Neil Giordano teaches film and creative writing in Newton. His work as an editor, writer, and photographer has appeared in Harper’s, Newsday, Literal Mind, and other publications. Giordano previously was on the original editorial staff of DoubleTake magazine and taught at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University.