Visual Arts Review: “Armenia!” — Art, Religion, and Trade at the Metropolitan Museum of Art

By David D’Arcy

Armenian cultural history has always been about survival: between Armenians preserving their art within the shifting boundaries of their homeland, and carrying their art beyond the country’s borders.

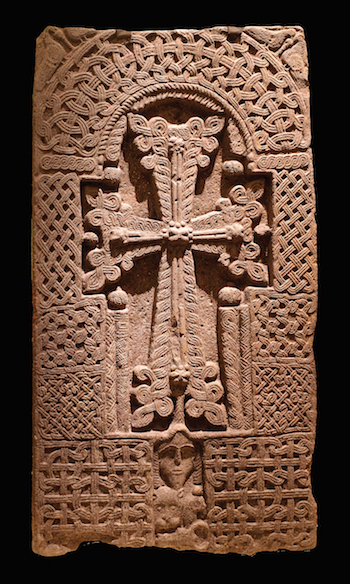

Armenia! at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (through January 13) contains a recurring object: the carved stone cross or khachkar, the heavy massive form Armenians customarily placed at graves and holy sites.

The exhibition’s 12-13th-century khachkars seem designed to be immovable; they were carved and deployed by the thousands to serve as Christian symbols in landscapes that bordered on territories controlled by regimes of other faiths. These heavy crosses asserted permanence, acts of defiance in the face of past campaigns to displace and exterminate embattled Armenians. The strategy, if it was one, didn’t always work.

Campaigns to eradicate these Christian symbols continue. In 2006, soldiers in neighboring Azerbaijan destroyed some 1400 khachkars in an Armenian cemetery. The desecration can be viewed below.

The revelatory Met exhibition of stone carvings, textiles, books, reliquaries, and jewelry assembles fragments of a people under siege, retracing cultural/artistic dispersions that took place long before the Genocide of 1915 drove the Armenians who survived it out of Turkey. The gathering features 140 objects from the 4th to 17th centuries, many from Armenia and never loaned before. This may sound impressive, but the selection feels sparse, especially after you reach the show after walking through galleries packed with Greek and Roman works.

Many of the Armenian objects, such as the khachkars, are variations on elemental images. A “radiate” cross in silver from the 11th-12th century includes a halo of round forms surrounding it, suggesting a pre-Christian Tree of Life motif. Also on view are stone effigies of churches, sturdy yet delicate scale models in the characteristic style of many-sided, turret-like structures. Some of these buildings still stand in Armenia today or lay in ruins across its border with Turkey.

The show’s catalogue is titled Armenia: Art, Religion, and Trade in the Middle Ages. At the exhibition’s core is a paradox – this unique culture, the world’s first Christian nation (301 AD), was also a constant cultural borrower from places where Armenians traded, traveled, and fled. That ambitious radius extended from Egypt to Russia, to Iran and India and China.

An example of a khachkar in “Armenia!” Photo: courtesy of the MET.

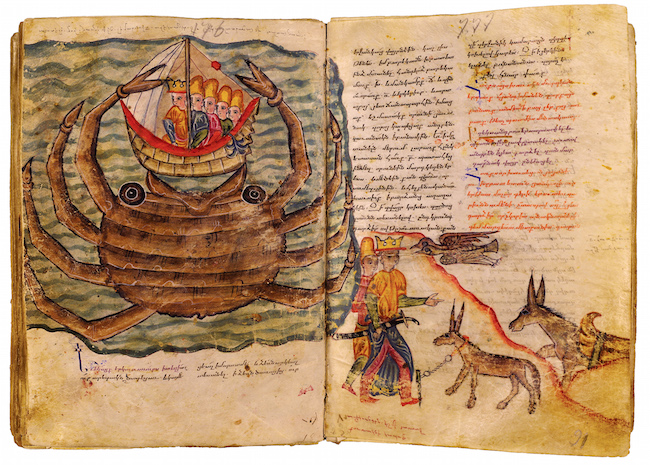

Art follows capital, and that’s what happened as Armenians became key players along trade routes, bringing objects and materials from one location to another. As merchants grew wealthy, they became the catalysts for a fascinating merging of style and traditions. A lattice-like scene of the Sacrifice of Isaac from an Armenian Gospel book (1455) evokes Persian or Indian Moghul painting, as does a page-sized portrait (1630) of an Armenian bishop clad in blue from Isfahan in Iran.

Alongside three massive khachkars, we also see more ambulatory objects, such as jewelry, for which Armenians became known. Books, central to Armenia’s Christian liturgy, could be wryly ornamental as well, sometimes reflecting an unexpected spirit of whimsy in their illustrated Bible scenes. In a fiery Last Judgment, for example, we see scenes of men being eaten by fish that are so wild they barely seem to be from this world.

Books were transportable but Armenian libraries were destroyed when cities were sacked. Etchmiadzin, the site of the mother church of the Armenian Apostolic Church, is the source for many of the surviving volumes on view in this exhibit.

Most of Armenia! (doesn’t the exclamation point make you think of Broadway’s latest pop-celeb spasm?) will be new to the museum-going public. Still, even for those schooled in this culture, the experience of the Armenians who flourished in New Julfa (the Iranian city of Isfahan) might be a surprise.

Armenians who in 1606 were ousted from the trading city of Julfa in Nakichevan (near the current Republic of Armenia) by Shah Abbas I of Persia, were resettled in the city of Isfahan, whose rulers coveted their silk sources in the East. Isfahan prospered. So did the Armenians of New Julfa, where their lavishly decorated churches still stand today.

From Lebanon, in a long display case, is an omophorion, a narrow 17th-century crimson shawl worn by priests, embellished with crosses in metallic thread. Its memorably soft color reflects its extraordinary condition; the cloth’s hypnotic glow is serene rather than emphatic. (Its beauty serves as a reminder that so many other objects from Armenian churches did not survive.)

Some objects loaned from Etchmiadzin, such as the “radiate” cross, were excavated at Ani, an Armenian city that flourished from the 10th to 14th centuries on what is now the Turkish side of the border between the Republic of Armenia and Turkey. Once a robust location for churches and palaces — and largely abandoned (after repeated sieges) since the 1500’s — Ani was explored, and then documented, by Russian archaeologist Nicolai Marr around 1900.

A page from “The Romance of Alexander,” a collection of legends concerning the exploits of Alexander the Great. Copied and painted by Zak’aria Gnuni in Rome (says Kouymjian 2012). The manuscript was received in 1916 from Varag. Photo: Courtesy of the MET.

Another source on the history of Ani is the Armenian priest and author Krikor Balakian (1876-1934), who visited city’s ruins with a religious delegation in 1909. In The Ruins of Ani, an account of Balakian’s trip (translated by the priest’s grand-nephew, the poet and chronicler Peter Balakian), he conveys his wonderment at what he saw.

Just re-published, The Ruins of Ani is an essential companion to the Met exhibition. Born in Anatolia, Krikor Balakian was educated in Germany (where he studied architecture and engineering) before he entered the priesthood. He was one of 250 intellectuals arrested, detained, and deported for extermination in the Syrian desert in 1915. He managed to escape and, under a series of disguises, survived the Genocide that killed an estimated 1.5 million Armenians, documenting that ordeal in Armenian Golgotha (1922), published in English in 2009.

Balakian’s 1909 chronicle envisions a place of distinctive architectural genius, one that was often hyperbolized as “the city of a thousand churches.” Arriving at the ruins, he quotes Dante — “what is more grievous and heartrending than to recall the glory of past days when one is living in days of misfortune.” Already, in 1906, three years before his trip to Ani, thousands of Armenians had been massacred in Adana, Turkey. Much worse would follow.

The exploration of Ani in Balakian’s account comes off as a sort of parallel journey to the exhibition’s presentation of Armenian places in medieval times. Armenian kings and clans are not necessarily heroes for Balakian. But he praises Trdat, Ani’s initial architect, who also restored the dome of Hagia Sofia in Constantinople after an earthquake in 989. Balakian’s tone becomes triumphalist when he declares that the Gothic architecture of Europe had its roots in Ani. He may be exaggerating, but the Met exhibition shows that there were plenty of cultural affinities.

Unfortunately, Balakian’s dreams of preserving Ani’s legacy were cut short with the Turkish extermination campaign of 1915. Countless religious and cultural objects were pillaged and destroyed during the Genocide. In 1922, orders came to have Ani’s towers and parapets reduced to rubble. A local commander refused to comply. Ani still stands, but it is under Turkish control — there are few official acknowledgments that it was ever Armenian. A brave Turkish philanthropist who led talks to have the site restored was jailed two years ago.

Armenian cultural history, reflected in the Met’s unprecedented range of objects, has always been about survival: between Armenians preserving their art within the shifting boundaries of their homeland, and carrying their art beyond the country’s borders. This exhibition is an important step in making the world aware of this rich, if fraught, interplay.

David D’Arcy, who lives in New York, is a programmer for the Haifa International Film Festival in Israel. He reviews films for Screen International. His film blog, Outtakes, is at artinfo.com. He writes about art for many publications, including The Art Newspaper. He produced and co-wrote the documentary, Portrait of Wally (2012), about the fight over a Nazi-looted painting found at The Museum of Modern Art in Manhattan.

Tagged: Armenia Culture, Armenia!, Armenian Art, Christianity, David D'Arcy, khachkar