Rethinking the Repertoire #22 – Florence Price’s “Mississippi River Suite”

It is one of the enduring ironies of classical music that so much of today’s repertoire was written by such a small number of people. This post is the twenty-second in a multipart Arts Fuse series dedicated to reevaluating neglected and overlooked orchestral music. Comments and suggestions are welcome at the bottom of the page or to jonathanblumhofer@artsfuse.org.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

“Unfortunately the work of a woman composer is preconceived by many to be light, frothy, lacking in depth, logic and virility,” Florence Price wrote in a candid letter to the Boston Symphony’s music director, Serge Koussevitzky, in November 1943. “Add to that the incident of race – I have Colored blood in my veins – and you will understand some of the difficulties that confront one in such a position.”

In those two sentences you find the fundamental conundrum that the Arkansas-native, New England Conservatory-trained Price faced throughout her career. Born in Little Rock in 1887, she displayed early musical talent and, graduating high school at fourteen, enrolled at NEC, where she majored in organ and piano performance, while also studying composition with George Whitefield Chadwick.

Returning to the South, she taught at schools in Arkansas and Georgia, before resettling in Little Rock in 1912 and marrying Thomas Price, an attorney. Due to rising racial tensions, the family (Price and her husband had two daughters) relocated to Chicago in 1927 and it was at this point that her compositional career really began to take flight. She immersed herself in the city’s vibrant African-American cultural scene, joining the R. Nathaniel Dett Club for Music and the Allied Arts, took courses at various local music schools (including the American Conservatory of Music, Chicago Musical College, and University of Chicago), and saw her first scores published by the G. Schirmer and McKinley houses.

Price and her husband divorced in 1931, after which time she and her daughters lived with Price’s former student and friend Margaret Bonds. By this time, Price’s career was in full swing: she worked as an organist for silent films, wrote and orchestrated music for WGN radio, and, through Bonds, came to be connected with several important figures in the black artistic community, Marian Anderson and Langston Hughes chief among them.

Most significantly, in 1932, Price’s Symphony in E minor was awarded the first prize in a competition sponsored by the Wanamaker Foundation. Frederick Stock led the world premiere performance with the Chicago Symphony, making Price the first black female composer to be performed by a major orchestra. What’s more, the Symphony was received with public and critical acclaim: “It is a faultless work,” the Chicago Daily News proclaimed, “a work that speaks its own message with restraint and yet with passion…worthy of a place in the regular symphonic repertoire.”

Even so, Price’s initial symphonic success didn’t break the taboos surrounding her gender and race. However, she continued to compose prolifically and was performed more widely, receiving performances from ensembles as varied as the Detroit WPA Concert Band, Pittsburgh Symphony, and the Musicians Club of Women. John Barbirolli commissioned a piece from her for his Hallé Orchestra. Anderson regularly sang her arrangements of spirituals.

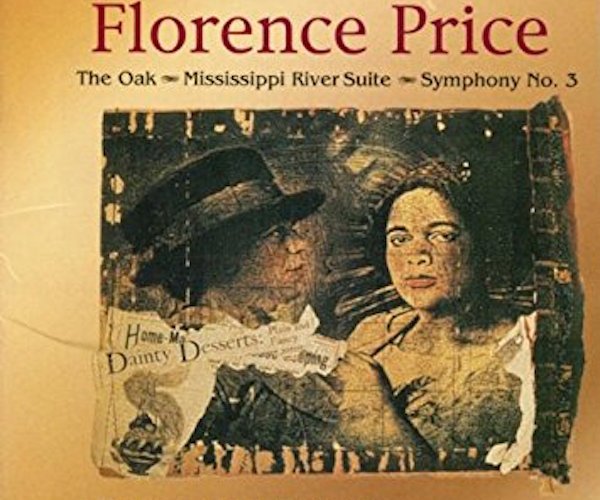

Florence Price — a composer to be reckoned with.

Clearly, she was a composer to be reckoned with: a musician with a strong, distinct voice, who had something to say, and whose work appealed to an impressive cross-section of prominent musicians of her day. What did her music sound like and what made it so remarkable?

Nearly all of Price’s compositions draw on her African-American ancestry. Indeed, the rhythms and melodies of traditional black songs and spirituals mark many of her works, though not always in obvious ways. Her music “uses the organizing material of spirituals,” Indiana University doctoral student and Price specialist Marquese Carter told the New York Times a few months ago. “You may not hear direct quotation, but you will hear playing around with pentatonicism, playing around with call and response, some of these organizing principles that African-American scholars like Amiri Baraka have pointed out as indicative of black musical discourse.”

The Mississippi River Suite, which Price wrote in 1934 and dedicated to her mentor Arthur Olaf Anderson, is more obvious in its allusions to the African-American musical experience than others. A near-thirty-minute-long score, it makes an excellent introduction to Price’s larger work (on top of being a superb piece in its own right). Its concept follows a pattern similar to the one traced in “The Moldau” from Bedrich Smetana’s Ma vlast, imagining a boat cruising down the mighty river from north to south, and the music depicting scenes encountered on its shores along the way.

The Suite falls, more or less, into four big sections, beginning with an evocation of dawn along the Mississippi’s banks. Lonely melodies; rich, noble chorales; imitations of bird song and nature alternate in a stately procession that leads, without pause, to the Suite’s second part.

Here, the music begins marking its geographic progress towards New Orleans with prominent woodwind lines and colorful percussion scoring conjuring up an imagined Native American landscape.

The Suite’s second section gives way, in turn, to the work’s most substantial part, one built around direct quotations of a series of Negro spirituals, plus some popular songs, echoes of jazz, and original music by Price. The four spirituals – “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” “Stand Still, Jordan,” “Go Down, Moses,” and “Deep River” – draw out some of Price’s most energetic writing in the Suite, punctuated as they are by turbulent accompanimental gestures and snare drum rolls.

Also some of the Suite’s most expressively powerful sections, especially as the climax of the work rolls around in its fourth and final part: the various melodies are piled one on top of the other with “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen” ultimately dominating the texture before the music fades into the distance.

After Price’s sudden death from a stroke in 1953, her music largely fell into oblivion. In the last couple of decades there’s been a notable uptick of interest in her output, though it remains largely unperformed by the country’s major orchestras and ensembles.

Why? Well, just go back to Price’s letter at the beginning of this entry. “Florence Price is a representation in music of what it means to be a black artist living within a white canon and trying to work within the classical realm,” Carter went on to tell the Times. “While [she] was quite proud of her accomplishments, she always felt like there was a limitation on the reception of her music, because of her race and because of her gender.”

That last seems, however unfairly, to have been the case. And, however easy it might be to understand the circumstances for it, Price’s lack of acceptance into the American canon is shameful. She was a composer of a body of music that hails from a unique perspective, one that, much like jazz, sought to integrate elements of African-American and European musical traditions, and did so energetically. Price wasn’t the early 20th century’s only important black American composer – William Grant Still, Ulysses Kay, and Will Marion Cook are three others who quickly come to mind – but she was a leader among them and the time for a reassessment of her work is at hand.

Today, when fresh thinking about traditional assumptions relating to race and gender is starting to affect noticeable social change, there’s maybe some cause for optimism that Price’s music will be rehabilitated (the recent rediscovery and recording of her Violin Concerto no. 2 adds some drama to her story). Has her time, like Mahler’s, finally come? One certainly hopes so.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: African-American composer, Florence Price

In the review, you mention composer Will Marion Clark, as a peer of Stills and Kaye:

“Price wasn’t the early 20th century’s only important black American composer – William Grant Still, Ulysses Kay, and Will Marion Clark are three others who quickly come to mind – but she was a leader among them and the time for a reassessment of her work is at hand.”

I have played no composition, heard or read about Will Marion Clark. There is a Will Marion Cook that comes up in searches for Clark. Could you please provide more information about Clark?

A mistake: it should be Will Marion Cook — I have corrected in the piece.