Book Review: “Convenience Store Woman” — Selling on Empty

Convenience Store Woman is an achievement — a satiric look at a mind that is intent on remaining empty.

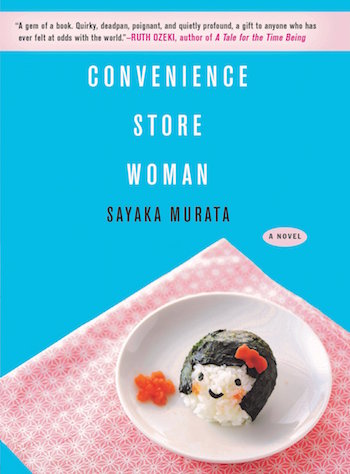

Convenience Store Woman by Sayaka Murata. Translated from the Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori. Grove Press, 163 pages, $22.

By Grace Perri Barnes

As a preschooler, Keiko—the anomalous, charming star of Sayaka Murata’s Convenience Store Woman—discovered a dead bird with her schoolmates. While the others wept and arranged for a makeshift funeral, Kieko suggested they ought to eat the thing. It serves as the earliest in a series of adolescent incidents that marks her as a misfit — her mother was petrified. To spare her family embarrassment, Keiko learned to keep quiet as she grew up. As a result, she developed a talent for extreme practicality — and an attenuated emotionality. She transforms herself into a kind of sophisticated robot; a shrewd observer of social behavior, capable of nimble mimicry, but impervious to the joy and anguish we might consider to be a sign of the human condition.

At the novel’s opening, Keiko is 36 and, with 18 years of cashiering and shelf-stocking under her belt, she’s the longest-serving employee at her local Smile Mart, a 24/7 convenience chain in Tokyo. “I was reborn as a convenience store worker,” she tells us and indeed, outside of her dedication to competence at work, she is a person without passion or project. She looks after herself solely for the sake of the store: “Sleeping, keeping in good physical shape, and eating nutritiously were all part of my job.” At work, where order is maintained through a series of prescribed interactions, Keiko welcomes respite from the fussiness of everyday social participation, which to her seems to be governed by rules that are opaque and benign. Before the start of a Smile Mart shift, uniformed employees chant a series of customer greetings and friendly phrases in unison; it is an identity-surrendering process that Keiko adores.

To preserve a veneer of normalcy, Keiko establishes a few casual friendships, parrots the manner of speech and dress admired by her coworkers, and keeps up with doings in her family. As she ages, despite her efforts, her peers increasingly regard her with the bafflement and scrutiny she worked to shrug off in childhood. She is a sedulous worker, a harmless person, and apparently content; yet, to others, her lack of ambition regarding career, marriage, and motherhood are bewildering and disorientating.

Despite her android-like behavior, Murata’s narrator is affably clumsy, unwittingly funny, and troublesome. She is indifferent to social processes and sentimentality: she operates with a machine-like focus on end results. The laws of conduct others follow in addressing problems that need a quick fix—a crying baby, a fight between schoolboys—strike her as inefficient hand-wringing. It’s not just that she eschews good manners; her theoretical solutions tend to require violence or make use of humiliation. (Occasionally, they are deadly.) Like a child, Keiko is astute in observing that the social code requires much arbitrary rule-following. She is also equally ignorant of the reasons behind civilizing customs.

Action is generated in a mostly flat storyline after Keiko becomes frustrated when she is asked — fourteen times over a two-week period — why she remains unmarried. She meets a man similarly struggling to fit in and considers contracting him to be her pretend-boyfriend. (Like Keiko, some of the guy’s social critiques touch on truths. Unlike her, he may be something of a sexual predator; he is probably an outsider for good reason.) As an experiment, Keiko begins talking about her romantic prospect to the folks in her circle, though she is sloppy in delivering the cover story. Her new beau comes off to them as a leech and a cheater. The novel’s most resonant bit of social commentary turns on this misfire: Keiko finds that her peers are more satisfied to see her in an unhealthy relationship than contentedly alone. For them, Keiko deducts, even the most miserable courtship is “comprehensible.” Indifference to romance is unfathomable.

Convenience Store Woman was released two years ago in Japan, where the 24-hour convenience store is an economic keystone and fixture of modern life. Its English translation comes along at a propitious time, given rising concerns about workers’ conditions and the rise of automation. As marketplace giants compete for levels of profit and productivity, how is it shaping our inner lives, distorting human desire? Murata’s just-below-the-surface acerbity is most skillfully deployed in examining how what we do distorts what we are.

Author Sayaka Murata. Photo: Bungeishunju Ltd.

Keiko’s story impishly riffs on a treasured capitalistic fairy tale—hers is not quite the self-made man mythos, but the mythos of the low-wage worker. The claim of economies like Japan’s, as in the United States, is that work, no matter how poorly paid, is inherently virtuous. (The virtues of laziness are reserved for the rich.) The promise is that dedicated effort inevitably leads to success and the joys of consumerism. Those with the requisite diligence and pluck will be rewarded, like the scrappy, somewhat inhuman hero of Horatio Alger.

But Murata presents an ironic spin on the rags-to-riches hero’s journey, imagining the low-income, downwardly mobile employee version. Her heroine attains optimism and fulfillment by depriving herself of aspiration entirely. The same facets of Keiko’s personality that make her proficient in the workplace exempt her from the normal human experience. She is constitutionally suited to the needs of the corporation, not because she is greedy or cruel (both are beyond her register), but because she is focused only on output. She lacks, too, an emotional gradient, an id, a hobby. And, most necessarily, she has no desire for money beyond exactly what she is paid, no interest in the comforts her hourly rate prohibit. The standard protagonist progressing through the realm of work exemplifies the qualities that lead to personal and financial accomplishment. But Murata cheekily theorizes on the set of traits one must possess in order to derive complete satisfaction from the common workforce experience. What kind of personality is content to never rise above his or her station?

In this translation, Murata’s prose is predictably simplistic and repetitive, as routine as the rhythm of Keiko’s life. The protagonist often muses on stagnation, and there is a stagnant quality here, an odd sensation of always being somewhere in the middle of the story, even as its final pages approach. To execute this static of a world requires care. It’s a stylistic choice that, like the novel’s concept, risks tedium. And, at times, the narrative runs aground. The redundancies become tiresome and, however intriguing Keiko is as a concept, there’s only so long one wants to stay stuck inside her one-track mind. But this flaw can be forgiven, given the ample rewards of this peculiarly jaunty narrative. Convenience Store Woman is an achievement — a satiric look at a mind that is intent on remaining empty.

Murata, who was Keiko’s age when the book was first released, works part-time in a convenience store herself. Of the novel, a prolific seller and prize-winner in Japan, she has said: “It was my first attempt to write about extraordinary people.” The result is more than just brief, breezy, and pithy — it is a look at how extraordinarily frightening ordinary is turning out to be.

Grace Perri Barnes has worked in publishing and journalism in New Orleans and Washington, DC. She is currently in editorial production at Politico and freelances on books to other publications.

Tagged: Convenience Store Woman, Grace Perri Barnes, Grove-Press, Japanese fiction