Film Review: “The Executioner” — Death Be Not Pedestrian

In this 1963 masterpiece, Luis García Berlanga entertainingly but ruthlessly lampoons the cruelties and absurdities of Spanish life under dictatorship.

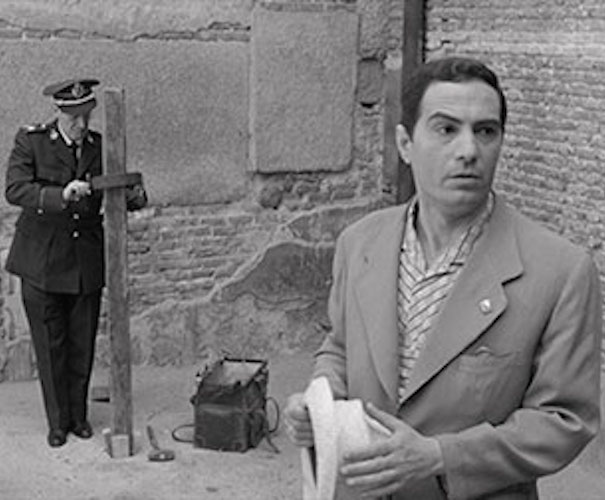

A scene from 1963’s “The Executioner,” released by The Criterion Collection and currently streaming on FilmStruck.

By Matt Hanson

Though not as well known outside of his native Spain, Luis García Berlanga is considered by many critics to be, along with his countryman and peer Luis Bunuel, one of the masters of Spanish film. His style is not as blatantly surreal as Bunuel’s, but beneath the whimsical tone of Berlanga’s films festers a dark satirical vision every bit as subversive. The director/screenwriter constantly outwitted fascist censors throughout the ’50s and ’60s, but he did not elude suspicion: Berlanga was labeled “a bad Spaniard” by Franco himself.

Undaunted by political pressure, Berlanga entertainingly but ruthlessly lampooned the cruelties and absurdities of Spanish life under dictatorship. His 1963 masterpiece The Executioner, recently released by Criterion and currently streaming on Filmstruck, is a deceptively whimsical black comedy about capital punishment and the dangers of normalizing life under strongman autocracy.

We first meet the eponymous executioner, a wizened and unassuming old man with the subtly religious name of Amedeo, right after an ordinary morning spent garroting a condemned man. The old fellow has a doddering, septuagenarian charm; he goes about his business matter-of-factly and with a certain pride. At least he’s killing people with the proper professional touch, he explains. The Americans use electric chairs hooked up to thousands of volts! Affably bumming a smoke from one of the prison guards, he says he’d like to quit smoking (it’s bad for his wheezing lungs), but he just doesn’t have the willpower. The newly filled casket is carried past him and he doesn’t bat an eye.

Amedeo lives in humble lodgings with his buxom daughter Carmen, who worries about spinsterhood; all of her former suitors have been scared off by the possibility of marrying into the family business. What’s a girl to do? Luckily, a hapless local undertaker named Jose Rodriguez, amiably played by Italian comic actor Nino Manfredi, winds up in Amedeo’s apartment and laments that he too has a similar romantic predicament. Nobody wants to marry an undertaker. It’s a perfect match. But when Amedeo catches the two of them in the middle of an afternoon tryst, he reacts as any family values traditionalist would. He’s scandalized: “My own daughter, naked! In my own apartment!”

Many of The Executioner’s plot elements are classic sitcom material. Characters act and react to each other with a high-spiritedness that belies the unpleasant facts of their existence: cramped living conditions, economic anxiety, indifferent bureaucracy, and the looming fact that the new man of the house will eventually have to take over the macabre family business. Jose isn’t the least bit interested in the business of death; he would rather fix cars instead. But with a surprise baby on the way — and the pressing need for the government’s approval of a new apartment — Jose finds himself reluctantly signing on for his father-in-law’s gruesome job.

Thankfully, Berlanga’s scathing eye for the way people internalize their society’s oppressive modes of behavior is not lost despite the story’s humor and antic pace. Amedeo casually demonstrates his garroting technique on a friend’s neck (via a rolled-up newspaper) at a picnic; his fascinated audience nods along. When Carmen reveals her pregnancy to an antsy Jose, she automatically defers to his male authority on whether or not to keep it. At certain points in the film Jose enthuses over the amount of extra money he gets for burying a child; he anxiously breaks up a street fight over someone winking at someone else’s wife, in case he might suddenly be called on to follow through on his new obligation.

Sacred shibboleths of Spanish culture are turned into hilariously screwball gags: a church singer gargles holy water, Jose’s pants fall down when he asks for Amedeo’s blessing on his marriage, Jose’s funeral attire includes floppy Renaissance style hats and cloaks. Berlanga’s brilliance lies in his subtle use of irony: each disturbing detail suggesting the underlying terror of life under a dictatorship is presented casually. Death is a brutally pedestrian thing; the characters take the grotesque mechanics of their social setting in stride — until the noose of the plot begins to tighten.

Jose is enjoying a ritzy state-sponsored vacation for him and family when he learns that he will have to leave early (before his official first day) in order to kill a condemned man. He pleads not to be involved, but to no avail. The warden informs him that he must do his job; after all, Jose will be administering God’s own grace to the poor wretch. Amedeo tries in vain to reassure Jose that the request is simply a formality; most likely the sentence will be pardoned at the last minute. He simultaneously reminds him, with an expert’s concern, not to commit any technical errors. When Jose is forcibly led off to do what must be done, it becomes difficult to tell the difference between the executioner and the condemned.

Berlanga’s spirited, caustically assured direction pokes at the pleasures of amorality. Barbarity becomes normal when society accepts state-sponsored inhumanity without demur. Jose sullenly returns from his first execution and swears that he’ll never do it again. Amedeo waves the discomfort off, remarking that he said the same thing after his first time and these qualms didn’t stop him from making a good living. As he holds his newborn grandson in his arms, Amedeo smiles, blissfully unaware of how he exemplifies not just the banality of evil but the evil of banality: it’s all in a day’s work.

Matt Hanson is a critic for The Arts Fuse living outside Boston. His writing has appeared in The Millions, 3QuarksDaily, and Flak Magazine (RIP), where he was a staff writer. He blogs about movies and culture for LoveMoneyClothes. His poetry chapbook was published by Rhinologic Press.

Tagged: black comedy, FilmStruck, Franco, Luis Garcia Berlanga, Matt Hanson, The Criterion Collection