Book Review: Altamont — Rock’s Worst Day?

As a work of history, a journalistic account, and an astute study of an immense subculture festering with incompatible elements, Altamont is so engrossing that it almost disarms criticism.

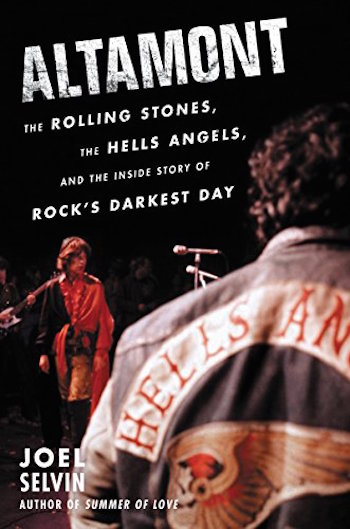

Altamont: The Rolling Stones, the Hells Angels, and the Inside Story of Rock’s Darkest Day by Joel Selvin. HarperCollins, 358 pp. $27.99 (hardcover)

By Blake Maddux

At the time, the free concert at the Altamont Speedeway east of San Francisco on December 6, 1969 seemed to be a good idea. Although its location had to be moved from two accommodating locations to one that was decidedly less so, the impressive gathering still attracted several hundred thousand young rock ‘n’ roll fans eager to take in a day of performances by Santana, Jefferson Airplane, The Flying Burrito Brothers, Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, The Grateful Dead (who didn’t end up making it to the stage), and The Rolling Stones, who were poised to become the most popular (intact) band in the world.

Unfortunately, Murphy’s Law was in full effect on this fateful day, helped along by greed, ego, intransigence, and fear. The Altamont Free Festival climaxed in the fatal stabbing by a Hells Angel of an armed 18-year-old African-American man named Meredith “Murdock” Hunter. He was not the only fatality that followed what many had hoped would be the west coast version of Woodstock, which had occurred three-and-a-half months earlier.

Shortly after the event, an in-depth report by the then-fledgling magazine Rolling Stone called it “rock and roll’s worst day.” The established but not yet legendary music journalist Greil Marcus confessed that “it was the worst day of my life” and added, “I don’t care if I never hear another rock and roll record ever again.”

In the popular imagination, Altamont has endured as the photographic negative of Woodstock, the definitive moment that the sixties died.

Now, nearly 47 years later, stalwart rock journalist Joel Selvin proclaims that December 6, 1969, was “rock’s darkest day” in the subtitle of his new book on the subject.

Selvin became a music critic at the San Francisco Chronicle in 1970 and is the author or co-author of more than a dozen books. If Altamont: The Rolling Stones, the Hells Angels, and the Inside Story of Rock’s Darkest Day is typical of the rest of its author’s work, then those unfamiliar with his writings should immediately clear his or her reading schedule and begin to catch up.

A review is not the place for a drawn-out rehashing of a book’s content. Thankfully, there is a brief passage in Altamont that provides a handy summary without being a spoiler:

The full enormity of the situation was crashing down on the Stones finally. The rushed preparations for the show, the absence of a police presence or any sort of practical security for that matter, the low stage, the scorched earth from the campfires of burnt garbage, the bad drugs and strong wine, the physical harm to the members of other bands who’d played that day, and the very real dangers that the Angels posed—all of it seemed to converge in this moment of the Angel grabbing the microphone. … [I]t was clear that the Rolling Stones were not in charge….

As a work of history, a journalistic account, and an astute study of an immense subculture festering with incompatible elements, Altamont is so engrossing that it almost disarms criticism.

Granted, Selvin did not write this book from scratch. Material on this topic has been piling up around him throughout his adult life. The fact that all of this was being filmed to document the Stones’ triumphant 1969 return to America after a three-year absence meant that millions — including law enforcement officials and jurors — wound up witnessing some of Altamont’s psychically jarring moments in the 1970 documentary Gimme Shelter.

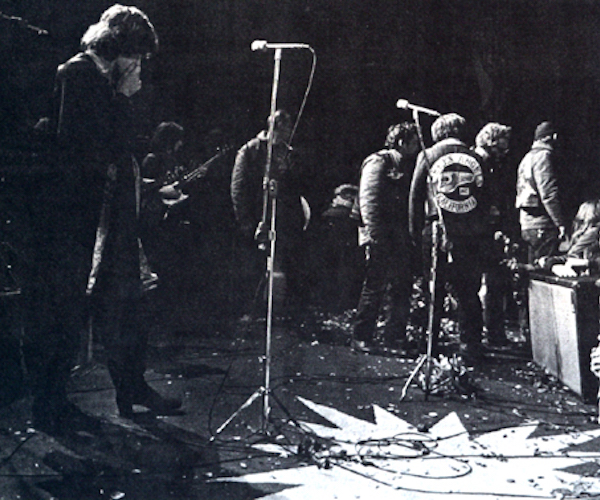

At Altamont, Mick Jagger stares in disbelief. Photo: Beth Bagby.

Selvin was born in Berkeley, CA, in 1950. He turned down the invitation from his friends to go to Altamont, but he was obviously interested in the San Francisco rock scene given that he started working for the Chronicle months if not weeks after the tragedy. Moreover, he had probably already done a good deal of the requisite research while writing books such as Monterey Pop, Summer of Love, San Francisco: The Musical History Tour, and The Haight: Love, Rock, and Revolution—The Photography of Jim Marshall.

However, his motivation for writing the volume was, as he confesses in the very last sentence, the fact that “the tale of Altamont left much to be told.” Apparently, there was plenty that he and his fellow writers had yet to unearth.

It is clear from the first page of the first chapter that Selvin has a gift for descriptive flair. Of the twenty-four-year-old Grateful Dead manager Rock Scully, the author notes, “Scully appeared like noting so much as Rasputin, his scarecrow frame topped with scraggly hair and an unkempt wispy beard. He had taken so much LSD, his pupils were little more than molten brown orbs floating in buttermilk.”

Each of the key figures in the ensuing tragic drama receives similarly detailed physical description and equally thorough biographical treatment.

Selvin also expertly elucidates what is probably the outstanding mystery to those who know the basic facts about Altamont but not the whole story: why were the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club serving as security?

It is easy for one to presume that it was part of Mick Jagger’s attempt to maintain his band’s bad boy image. After all, Selvin observes, the singer was none too keen on cops: “From the very start of negotiations for this tour, Jagger had been adamant: no uniformed police would be allowed inside any concert hall where the Stones were performing.”

“Altamont” author Joel Selvin. Photo: Deanne Fitzmaurice.

Moreover, the Hells Angels had experience at free outdoor concerts in the Bay Area (including the January 1967 Human-Be-In, at which Timothy Leary called on those within earshot to “turn on, tune in, and drop out”) and got along quite well with Haight-Ashbury hippies, who—like the notorious bikers—saw straight society as the common enemy.

Selvin devotes the whole of Part 3 to the aftermath of the disaster, including the trial of the knife-wielding biker. He is not afraid to affix blame to whom he feels it belongs, and he confidently attempts to undermine the myths of Altamont, particularly the charge that it was ‘the day the sixties died.’ It is on this point that he invites skepticism. It is not that Selvin is incorrect in his conclusions. But, in his effort to debunk the standard ‘end of the counterculture’ narrative, he seems to undermine his own argument.

“The events at Altamont were the result of the convergence of many fissures running through the counterculture,” Selvin opines. “A great many bills came due that day, as the axioms of the Summer of Love were put to test and failed like a wet paper bag.” So then, ‘the sixties died,’ it sounds like. But Selvin goes on to deny that that is what he is saying; he claims that “All the ideas and aspirations for the evolution of consciousness that were at the heart of the movement remain. That dream never died.” This statement is made after he has burst the tie-dye bubble.

Selvin also acknowledges that “Altamont brought the Achilles’ heel of the hippie movement into sharp focus.” Of course, a vulnerability can be exposed without being violated. If all those who travelled to and from, attended, and participated in the concert had completed the voyage unscathed, then one could reasonably say that the hippie movement had dodged the Paris’s arrow that was Altamont.

This was obviously not the case.

Does it matter if December 6, 1969, was “the figurative and literal end to the sixties and all that it came to represent…in some definitive, apocalyptic way”? No, not really. Selvin’s diagnosis comes off as more of an autopsy than he intended. But this uncertainty about Altamont as cultural harbinger, an act of prophetic finality, should not be taken as a flaw. This is a spellbinding volume about a dark iconic happening.

(On an interesting but not particularly relevant note, this is the second recently released book—the other being Never a Dull Moment: 1971—The Year that Rock Exploded—that subtly depreciates the legacy of the 1972 Rolling Stones album Exile on Main St., which many have long considered to be an unimpeachable masterpiece. Perhaps rock ‘n’ roll historiography is in the early stages of what will prove to be an ongoing trend.)

Blake Maddux is a freelance journalist who also contributes to The Somerville Times, DigBoston, Lynn Happens, and various Wicked Local publications on the North Shore. In 2013, he received an MLA from Harvard Extension School, which awarded him the Dean’s Prize for Outstanding Thesis in Journalism. A native Ohioan, he moved to Boston in 2002 and currently lives with his wife in Salem, Massachusetts.

I was there! We were the ones on the Honda that you could put in your car we were in front of the Hells Angels on the way in to the Concert, there has to be pictures of us. It was is a sight to see.