Classical CD Review: The New York Philharmonic plays Christopher Rouse (DaCapo)

There’s a lot of music by Christopher Rouse to appreciate, ponder, puzzle over, and study in what we’ve got here.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Anyone who thinks that the symphony is a spent genre clearly hasn’t been paying attention to Christopher Rouse of late. The New York Philharmonic’s (NYPO) former composer-in-residence proved himself one of the late-20th century’s most important symphonists when his First Symphony premiered in 1988. Coming more than fifteen years after the first performance of his Second, Rouse’s Third and Fourth demonstrate that he occupies that same space in the early-21st. At least that’s one big impression left by the handsome, new, all-Rouse release from DaCapo featuring his Symphonies nos. 3 and 4 as well as a pair of concertante works, Odna Zhizn and Prospero’s Rooms.

Echoes of Russian music – especially Prokofiev and Shostakovich – abound in the two wildly contrasting symphonies. That’s particularly apt for the Symphony no. 3, whose form is modelled on Prokofiev’s two-movement Second Symphony. A couple of gestures and quotations notwithstanding, Rouse’s is a bit more direct in its expression than Prokofiev’s: the driving, toccata-like first movement neatly distills its materials and the substantial theme and variations that follow offer episodes of sustained lyricism that call to mind passages in recent-ish Rouse pieces like Rapture and Friandises.

Similar recollections of Rapture – in particular, the bounding, sunny optimism of the second half of that piece – mark the bustling first movement of the Fourth Symphony. This is another two-movement score, though the contrast between each of its halves is far starker than in the previous Symphony. In the Fourth, composed for the NYPO’s inaugural Biennial in 2014, Rouse crafted music of real buoyancy and color for the opening movement. Essentially a rondo, it begins with a scurrying string figure that’s answered by syncopated brass and percussion gestures. These are constantly developed according to Rouse’s contrapuntal pattern and never lose their bright, optimistic touch. But this unalloyed, conflict-free music never seems quite settled or right, emotionally.

And that’s because, as it suddenly (and rather abruptly) disintegrates, it’s revealed that, underlying it, is some of the darkest, most unsettling music Rouse has crafted. This second movement channels the Rouse of Iscariot, Phaeton, and the Symphony no. 1, even if it doesn’t build to as anguished a climax as any of those classics of his from the ‘80s. Its materials are unrelentingly spare: recurring descending figures (plus a corresponding rising one); a long-breathed, chromatic melody over a chaconne-like accompaniment; a subdued chorale; and a canonic melody for high strings among them. The movement’s climaxes are almost decidedly anticlimactic, rarely rising above a forte dynamic. At the end, the music just stops, like the gears of a watch totally unwound. While its ultimate meaning remains enigmatic, this music is deeply troubling, its dualities and spiritual exhaustion somehow especially fitting for our age.

The album’s other two selections succeed to varying degrees. Odna Zhizn, a fifteen-minute-long meditation on the life of an unnamed person of importance to Rouse, offers page after page of striking ideas: string chorales underneath freely-notated woodwind solos and harp/keyboard filigrees; extended, evocative duets for solo clarinet and marimba; snarling, violent brass outburst; subtle transformations of driving rhythmic figures; and the like. Moments of tender beauty brush up against those of savage violence. Its quiet resolution suggests survival achieved through perseverance more than victory over oppression.

As for Prospero’s Rooms, a curtain raiser “inspired by” Poe’s “Masque of the Red Death,” let’s just say that it captures some of the air of menace found in the story. But the music never really corresponds to the brilliance of Poe’s prose: its gestures and melodies are unconvincing and don’t stick in the memory. Even Rouse’s evocation of the tolling clock – here realized by the combination of a gong, bell plate, and tam-tam – falls flat. It’s an odd misfire from a composer who’s often so good at conjuring up existential terror in his music.

Even so, this is a triumphant and important release. In addition to Rouse, the stars of this album are the NYPO and its music director, Alan Gilbert. Gilbert’s evidently ruffled some feathers during his tenure at the Philharmonic’s helm with his embrace of contemporary music (and supposed lack of sympathy for the core canon). But in his smart, eclectic curation of many types of new music he’s done what no music director since Pierre Boulez (who left in 1977) has managed: he’s made the Philharmonic culturally relevant again. If nothing else, that will be his legacy when he steps down – too soon – from the post next spring.

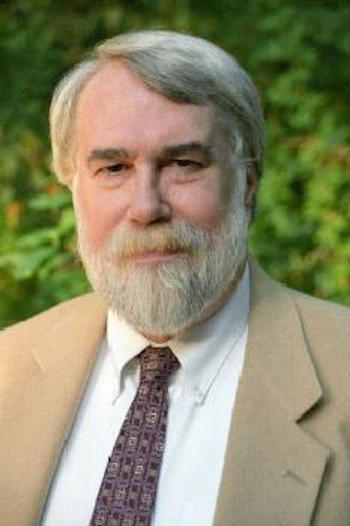

Christopher Rouse: some of his music is deeply troubling, its dualities and spiritual exhaustion somehow especially fitting for our age. Photo: Jeffrey Herman.

And the Philharmonic’s playing here demonstrates just how vital they are in this repertoire. Each of the performances are brilliant, incisive, filled with energy and life. That’s not to say that they’re flawless – each recording is drawn from a live concert and Rouse is a fearsomely virtuosic orchestrator – but they ably capture the excitement of good new music being unveiled for the first time by a world-class orchestra that’s fully committed to what it’s playing. DaCapo’s recorded sound is well-balanced and marred only (if such a word is warranted) by some extraneous stage sounds (mainly quick page turns in the orchestra); audience noise is negligible.

Indeed, my only real complaints are that, 1) of these four pieces, only the Fourth Symphony hasn’t been previously released, and, 2) as with the NYPO’s all-Magnus Lindberg recording (also from DaCapo) commemorating that composer’s residency with the ensemble, not everything the Philharmonic commissioned or played by Rouse over the last three years is represented. How nice it would have been to get a recording of Thunderstuck; of Rouse’s extraordinary Trombone Concerto; or the haunting, gorgeous one he wrote for flute. As with Odna Zhizn, Prospero’s Rooms, and the Symphony no. 3, some of those performances are already available through the Philharmonic’s own label; still, it would have been nice to have everything in one place.

That said, there’s a lot to appreciate, ponder, puzzle over, and study in what we’ve got here. Besides, in a matter of months the discography will need to be expanded again: Rouse’s Symphony no. 5 premieres in Dallas next February.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette

Tagged: Alan Gilbert, Christopher Rouse, DaCapo, New York Philharmonic, Odna Zhizn