Visual Arts Review: Leon Steinmetz — Picturing the Artful Comedy of Commedia dell’Arte

In this splendid exhibition, Russian-born painter and illustrator Leon Steinmetz displays a deep appreciation of the complexity of commedia dell’arte.

Leon Steinmetz: All The World’s a Stage…Commedia dell’Arte & Other Theater at Gurari Collections, Boston, MA, through July 31.

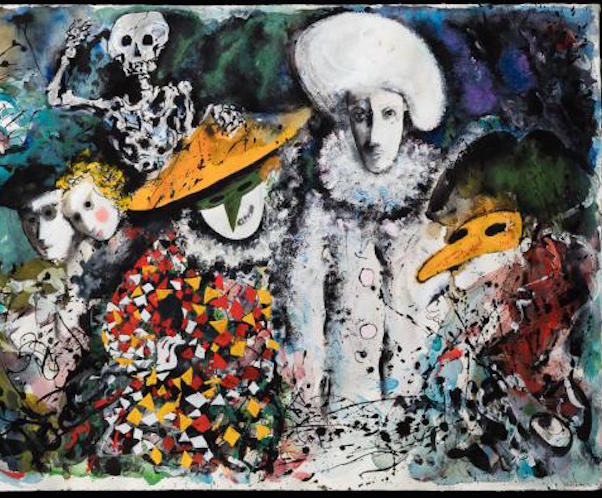

“We are not Going to Harm You 2,” Leon Steinmetz, 2016.

By Ian Thal

Some art plays up to our grand dreams about being heroes or superheroes. Commedia dell’arte deflates these fantasies, generating humor out of mundane but grotesque reality. From their humble sixteenth-century origins in the urban street theater of the Italian peninsula, commedia’s cast of characters have become comic archetypes of vice and folly. These figures have freely circulated throughout European culture, high and low, from oil painting to opera, from Punch and Judy shows to Pierrot and Pulcinella hawking absinthe and pizza. The iconography of the original form’s masks and costumes are sometimes discarded, but the characters have continued to thrive in other guises: Pantalone and Pedrolino are recognizable in The Simpsons‘ Montgomery Burns and Smithers; Il Capitano takes the form of Captain Zapp Brannigan in Futurama‘s animated 31st century. The names and costumes change, but commedia lives on.

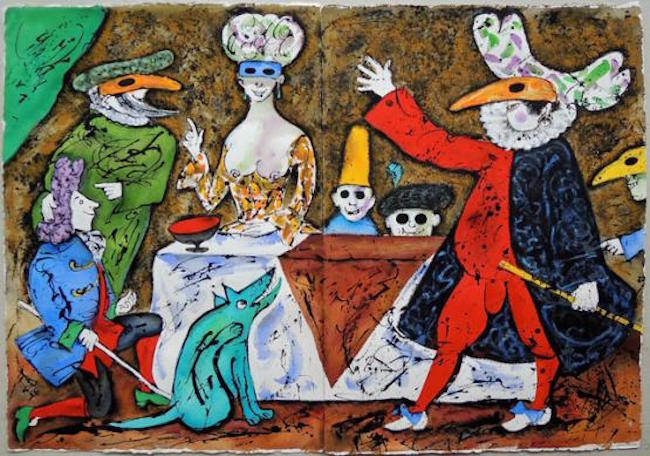

Russian-born painter and illustrator Leon Steinmetz has a deep appreciation of the complexity of commedia. In one of the works in this splendid exhibition, He Does Not Know What He Is Getting Into, he economically explores a number of farce motifs. A young inamorato, dressed in his showiest finery, including a large powdered wig, is on bended knee, asking the father of his beloved for his permission to marry her. Of course, the father-in-law-to-be is none other than Pantalone. (His red pantaloons do little to conceal an enormous organ. Whether it is his natural girth, or the product of trouser stuffing, or the era’s equivalent of penis-enlargement quackery is anyone’s guess.) The young lover’s mind is too occupied with his mission to recognize his future-father-in-law’s vulgarity, or to notice that his beloved’s breasts are spilling out of her dress (a popular lazzo, or piece of stage business, at the time). As the series progresses, Steinmetz keeps his central characters (including a flea-ridden, teal-colored dog) in the same positions, but changes their costumes and moves the supporting cast of Pantalone’s servants and demented relatives around them. My guess is that the artist wants to suggest the way commedia troupes improvise subtle alterations to their well-worn scenarios from performance to performance.

“He Does Not Know What He is Getting Into 1,” Leon Steinmetz, 2016.

In the series Carnival, Steinmetz introduces an expanded cast of characters and approaches. Initially, the commedia personnel dance and leap against a colorful and swirling background which, miraculously, does not overpower the bright costumes. Next, the cast reappears, making similar gestures, in a straightforward academic presentation: the costumes are less garish and the blank background is distracting. The third illustration smudges the characters, as if they are rebelling against the tyranny of neat lines. Finally, in the fourth part, the figures have become expressionistic gestures. Steinmetz seems to be serving up a thematic history story — the trials and tribulations of a vital popular art-form. First, it is formalized and codified into something safely entertaining, only to be rediscovered and reinvented by avant-gardists who have little patience for academic pieties.

There are edgy tonal shifts in the contrasting pair of paintings titled We are Not Going To Harm You. What appears to be Harlequin and Scapino lead the melancholic Pierrot to some lively festivities. The inamorati look on, prepared for a life happy ever after. Death appears as one of the celebrants, so all must be well. In the first painting, the bright watercolors suggest an unambiguously happy ending; even Pierrot might crack a smile. In the second painting, though, the pigments are darker and there are splatters of paint. Shadows on Pierrot’s face give lie to the title: the young lovers are empty-eyed, as if it has dawned on them that now that they have each other they have to figure out what to do next. Both Death and Pierrot’s friends sport menacing expressions. It is as if Steinmetz has painted the story from two perspectives — the wishful thinking of the audience versus Pierrot’s depressed vision of the way things are.

Commedia dell’Arte Dwarf General, Leon Steinmetz.

Steinmetz also explores commedia in smaller works. There is a series of miniatures, done with a fine-line pen, whose loose gestural feel somehow manages to evoke the disciplined images of Jacques Callot – the seventeenth century Lorrainian printmaker whose extant work provides our best record of the costumes, masks, and stylized physicality of commedia as it was originally performed. Yet there is an undeniable modernity to these pictures. Their titles — “Don’t beg me, it’s useless!” and “We’re all relatives, can’t you see it?” “I do now.” — suggest the captions in New Yorker cartoons.

A triptych of three court dwarfs (a general, a treasurer, and a poet) displays a less ecstatic side of Steinmetz’s imagination. Using colored pencils, the artist pays close attention to the subtle effects of light and shadow on faces, as well as on the pressed velvet and ruffled color of the treasurer’s robes, the wavy hair and finery of the poet, and the armor of the military officer. These works seem to be a response to a series by Callot — Les Gobbi — which documents a troupe of masked dwarf performers who appear to have entertained at the court in Lorraine. In contrast, Steinmetz’s dwarfs are not committed to amusement. The pain, humor, and pride on their faces suggest their personal struggles — they have to constantly prove their value as human beings.

Steinmetz is obviously steeped in the history of an old art form, yet he brings a refreshing modern sensibility to his triumphant evocation, via inks and paints, of the vibrant, lustful, melancholic, and very mortal heart of commedia dell’arte.

Ian Thal is a playwright, performer, and theater educator specializing in mime, commedia dell’arte, and puppetry, and has been known to act on Boston area stages from time to time, sometimes with Teatro delle Maschere. He has performed his one-man show, Arlecchino Am Ravenous, in numerous venues in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. One of his as-of-yet unproduced full-length plays was picketed by a Hamas supporter during a staged reading. He is looking for a home for his latest play, The Conversos of Venice, which is a thematic deconstruction of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. Formerly the community editor at The Jewish Advocate, he blogs irregularly at the unimaginatively entitled The Journals of Ian Thal, and writes the “Nothing But Trouble” column for The Clyde Fitch Report.