Dance Review: Paula Josa-Jones — Shape Shifter

In spite of my frustration about the music, I was deeply involved with this performance. Josa-Jones is a unique mover, totally committed to her movement, and totally moving in every body part.

Paula Josa-Jones: “Of This Body” at the Dance Complex, Central Square, Cambridge, MA, June 3 and 4.

Paula Josa-Jones in a scene from “Of This Body.” Photo: courtesy of the artist.

By Marcia B. Siegel

Paula Josa-Jones’s concert Friday night began in the street-level studio at the Dance Complex, with a surrealistic film montage of disembodied eyes, sections of antique street maps, feet making their way over stones, and some soft meditative music. For the rest of the evening, upstairs in the studio-theater, Josa-Jones performed three solos, The Traveler (terra incognita), Mammal, and Speak. Like the introductory film, the dances suggested floating identities, journeys but not destinations.

Josa-Jones led a well-regarded dance company in Boston for 15 years before decamping to Martha’s Vineyard in the 1990s. She’s now based in Connecticut. Her unusual background includes the intensive body-centered work of Laban movement analysis and Somatic movement as well as choreography and design. She’s trained horses and studied equine awareness. Her book, The Common Body: How Horses, Movement and Awareness Awaken Our Essential Humanity, was published this spring in the UK. Her concert at the Complex reflected all these influences. Without any didacticism, Josa-Jones gave us a finely crafted theater work that challenged the viewer’s imagination.

When we entered the studio, we saw what could have been a large pale rock, with two rocklike mats or quilts nearby, and a projected film of the outside of a speeding train. A kitschy tango was playing. The smallest of the mats heaved a bit, and a person began to emerge: Josa-Jones wearing layers, a loose shift over a t-shirt and black trousers, with a black clown’s cap over her head. She seemed to be some kind of creature, searching around her body with her hands, touching herself, reaching outward. Crossing the space, she seemed to be pulled off center, bending and arching her body, her arms skewing out at the joints. Though the creature’s behavior was primal, she never seemed without mind or intention.

She reached under the other mat and started pulling out some reddish cloth, then withdrew as if impelled away. Later she returned and tugged it all out, together with a bowler hat and a cane. The cloth, dyed in subtle shades of red, turned out to be a beautiful, oddly cut jacket. When she started to put it on, her thrusting arm led her into big whirling circles and the cloth swung out like that of a Dervish. Donning the hat and the jacket, she glided through the space, her movement growing more specific and detailed as she paused to try out different characters. She didn’t evoke their stories, only their appearance, their gestures. Like passengers on a train, they were only glimpsed.

The traveler passed through several more phases or spheres, with accompanying projections and music. There were bells and clouds, then a film montage of wrinkled paper or cloth. After a crash of thunder and a fall, the traveler plucked what may have been discarded newspapers from the quilt. The sound changed again: a chaotic overlay of rhythms with an accordion added into the percussion. The traveler’s gestures grew more agitated, into groping and grasping.

The sound and the screen changed again, to an expanse of flat water rippling in the sun, then more speeding trains. The woman made her way into the corner of the space, dragging the heavy quilt behind her. The dance was over but not the journey.

Mammal began with Josa-Jones crouching and nearly merging with a screen covered in amorphous shapes. She wore a long, layered dress with a sort of halter top that revealed her tattooed shoulders, upper back and arms. Late in the piece, she came close enough so the audience could see that she was wearing what might have been long gloves that came down over her fingers like claws. Despite the dance title, she didn’t literally imitate any animal, but she could have been channeling anything that walked on four legs, writhed on the ground, crouched and gazed around warily. We heard strangled screams, muted growls and screeches that could have come from a nighttime forest a long way away.

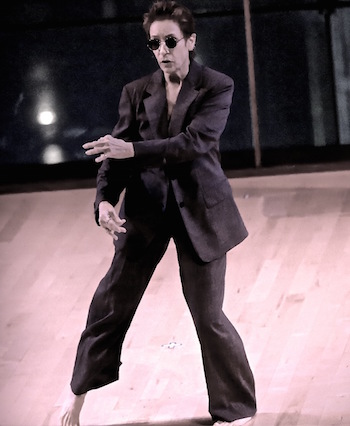

Paula Josa-Jones in a scene from “Of This Body.” Photo: courtesy of the artist.

The sounds in this piece (unidentified works by Fred Firth [sic] and DakhaBrakha) comprised an interesting, pan-ethnic mix with hints of African, Eastern European, and pre-verbal vocalizing. The dancer walked with clutching hands, at first to a two-note accordion bass line with percussion and trumpet notes and later to some chanting in high-pitched nasal voices. She slowly rolled away, to curl up and become part of the film projection again.

The last piece, Speak, might have been an improvisation. I only say this because, searching for it on the Internet, I found at least two other versions, all slightly different. But even if the movement was spontaneous, everything she did looked deliberate, if not rehearsed. Josa-Jones says this piece was prompted by the moves of an autistic relative. I thought it could have been a gender statement, or possibly a comment on aging.

She began seated on the floor with her back to the audience. Wearing a mannish suit and a black t-shirt, she rose and gestured around her body, as if getting dressed. Or perhaps checking her outfit for rips or moth-holes. Josa-Jones’s movement is so specific you want to assign a meaning to it, even as you realize it has no specific meaning.

She sits in a chair, spreading her legs wide, adjusts the small round shades she wears, fiddles again with her hands. When she gets up she swaggers a bit, falls into nameless characters while a soft man’s voice raps to a rhythm background, urging, “Let your hair down and let yourself move.” (No telling who this was; three names are credited in the program opposite Music.) When the dancer sits again, she pulls her legs together primly, gestures close to the body with trembling hands, as if primping before an unforgiving mirror.

In spite of my frustration about the music, I was deeply involved with this performance. Josa-Jones is a unique mover, totally committed to her movement, and totally moving in every body part. This show brought her dancing together with the sympathetic collaborators Paola Styron (direction/outside eye), Katherine Freer (projection design), Susan Hamburger (lighting design) and Pam White (photography and videography).

Internationally known writer, lecturer, and teacher Marcia B. Siegel covered dance for 16 years at The Boston Phoenix. She is a contributing editor for The Hudson Review. The fourth collection of Siegel’s reviews and essays, Mirrors and Scrims—The Life and Afterlife of Ballet, won the 2010 Selma Jeanne Cohen prize from the American Society for Aesthetics. Her other books include studies of Twyla Tharp, Doris Humphrey, and American choreography. From 1983 to 1996, Siegel was a member of the resident faculty of the Department of Performance Studies, Tisch School of the Arts, New York University.