Theater Review: Rebel Revels at the Poets’ Theater’s “Beowulf”

Everything in this stage version of Beowulf been given a Scandinavian flavor – special kudos to prosciutto for playing its role as boar’s meat quite well.

Beowulf: A Feast of Story, translated by Seamus Heaney. Adapted for the stage by David Gullette. Directed by Benjamin Evett. Staged by the Poets’ Theatre at the Multicultural Arts Center, Cambridge, MA, through December 20.

A scene from the Poets’ Theatre’s production of “Beowulf: A Feast of Story.” Photo: Andrew Brilliant

By Marcia Karp

Hwæt! Of all the things that might be offered for the coming solstice and the season of celebration, The Poets’ Theater has chosen Beowulf, that ancient, bloody Anglo-Saxon three-taled yarn. The audience is not invited into an auditorium, but into Heorot, the Danes’ mead-hall, to sit at roughhewn tables and eat Viking vittles, to solve Anglo-Saxon riddles and be toasted whether or not the strange answers have been discovered, to dance, sing, and perform a resurrection charm. Everything has been given a Scandinavian flavor – special kudos to prosciutto for playing its role as boar’s meat quite well.

The hit of the show, though, is Seamus Heaney’s 2000 translation of this story from the dark ages. David Gullette, the company’s Literary Director, has shaped the epic by adhering closely to its bones. Some stories within stories and story branches, such as the origin of a great gold hoard or the foretold danger of a coming marriage between ancient rival houses, have been pared. This is smart; there is enough to listen to in the ninety-minute focus on Beowulf’s three battles. Music and movement keeps the tales engaging and easy to follow.

The story-telling begins in Anglo-Saxon, which is an unexpected pleasure to hear. Then comes Heaney’s text, spoken for the most part by three Poets, who are joined and supported by three Thanes.

So! The great Geat Beowulf sails with some few fellows down from southern Sweden to the beset Spear-Danes in order to end the midnight snacking of the man-eating Grendel, a cursed descendent of the cursed Cain. It is just here, in Heorot on the Charles, where Grendel eats his last meal, but he doesn’t share our flat or steamed nut breads topped with Gjetost, a Norwegian marvel of cheese.

he grabbed and mauled a man on his bench,

bit into his bone-lappings, bolted down his blood

and gorged on him in lumps, leaving the body

utterly lifeless, eaten up

hand and foot.

This is to be Grendel’s final meal, for Beowulf is aroused and bests the beast in hand-to-claw combat. The battle is waged slowly, not a pantomime but a shadowy reflection of the text. A special sort of theatrical reality follows, when the full cast of six gathers to look in amazement at the imaginary battle trophy: Grendel’s arm and talon raised high onto the hall’s beams. It is practically impossible not to follow their wondering eyes, though it is almost sure that no bloody limb has been hoisted.

Gullette’s adaptation is more than a sinewy Beowulf. The text is skillfully divided between the Poets. The magisterial Johnny Lee Davenport speaks all of Beowulf speeches and, because he is a Poet, all of the narration about Beowulf. The actor has worked with director Ben Evett before on several of Shakespeare’s plays and with Bob Scanlan, the Poets’ Theater’s motivating engine and angel, in Gilgamesh. Gullette himself is the slightly dotty old Danish king, Hrothgar. After death has swept away the leader of the Ring-Danes, he takes his turn telling other parts of the story. The third Poet is Amanda Gann, who takes on many characters and their narrations. She recently has appeared in the Poets’ Theater’s production of Beckett, most impressively as Mouth in Not I and then immediately after in Pas Moi.

Heaney wrote in his introduction to his translation

I came to the task of translating Beowulf with a prejudice in favour of forthright delivery. […] What I had always loved was a kind of foursquareness about the utterance, a feeling of living inside a constantly indicative mood […]

The delivery of the poem is forthright and might at first seem without feeling, but that foursquareness is the ground against which the tales feel as if they mean something to the tellers. When Gann tells how Queen Wealhtheow, Hrothgar’s wife, moves among the men in the mead-hall, she is sly as she beguiles Davenport’s Beowulf, drawing him to follows her a few steps until he realizes he mustn’t. Again, when playing the coward Unfresh, Gann’s drunken envy is palpable enough to get laughs.

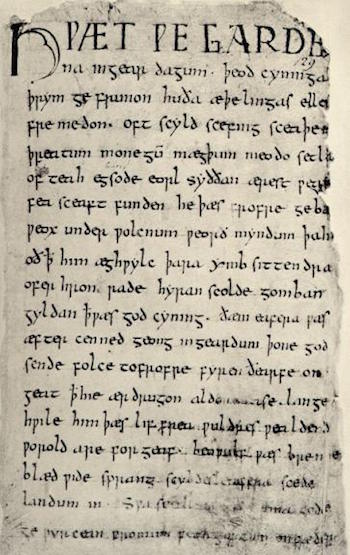

Opening lines of Beowulf. From the British Library Cotton ms, at least 1000 years old.

The three Thanes – Rebecca Lehrhoff, Jesse Garlick, and Rachel Wiese – each work with Liars & Believers, a Boston Theatre company. They serve as chorus, Baltic Sea, fear, wonder, Grendel’s mother, and Beowulf’s shield. They are unobtrusively everywhere, echoing what they hear and conveying characters’ emotions.

A favorite with the children in the mead-hall was the Viking hand-to-hand combat fought with swords, battle axes, and wooden shields that were worse for the wear after the fighting. Though one of the elements cut from the translation is the faint, but consistent, Christianity that coexisted with the Germanic warrior ethic, the audience twice is urged to utter a charm that will return a warrior from death. Only after the third fight is the vanquished Viking allowed to die and be dragged off unnamed and unmourned.

The program lists two musicians: Jay Mobley, music director and guitar, and Ethan Rubin, fiddle and kemanche, a Middle Eastern stringed instrument. But there were more than those being played up in the balcony. There were electronic sounds and woodblocks and something that gave sound to the waves as Beowulf made his sea crossings. Mobley and Rubin led the hall in song several times during the evening. Our text was WEOROLD CYNING, sung at top volume.

Beowulf becomes the King of the Geats, and, so to them, the King of the World. Beowulf, though, is among those few epics that have endured because it is not kingly power that is celebrated, but a healthy balance of power between the king and his people. The very word cyning holds within it the notion that the king is the son of the cyn, the people. When he kills Grendel, and then two more monsters, it is clear in the Poets’ Theatre’s performance that the audience is kin, through its fears and gratitude, to the Geats. A tale for then and now.

Arts Fuse feature on the making of Beowulf: A Feast of Story.

Marcia Karp has poems and translations in Free Inquiry, Oxford Magazine, The Times Literary Supplement, The Warwick Review, Ploughshares, Harvard Review, Agenda, Literary Imagination, Seneca Review, The Guardian, The Republic of Letters, and Partisan Review. Her work is included in these anthologies: Penguin Books’ Catullus in English and Petrarch in English; Joining Music with Reason: 34 Poets, British and American, Oxford 2004-2009 (Waywiser); and The Word Exchange: Anglo-Saxon Poems in Translation (Norton).

Tagged: Benjamin Evett, Beowulf, Beowulf: A Feast of Story, David Gullette, Johnny Lee Davenport