Best Books: Notable Volumes, For Better or Worse, in 2015

Our demanding critics supply lists of books that piqued their interest this of the year.

• The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen

Whatever you think or have thought about the War in Vietnam, whether for or against, and no matter how passionately, is likely to be simultaneously reinforced and contradicted by this novel. The Vietnamese narrator, known throughout simply as the Captain, tortures and is tortured, is fiercely communist and fiercely anti-communist, is as savagely pro-American as he is anti-American. The Captain is devoted to Ho Chi Minh Thought as much as he detests every last particle of that dogma.

This is a strong first novel by Vietnamese American writer Viet Thanh Nguyen.

• The Hilltop: A Novel, by Assaf Gavron (translated from the Hebrew by Steven Cohen)

Israel came into being to facilitate an ingathering of Jews but serves also, in fact, as point of origin for an outpouring of Israelis who want to try their luck in Diaspora outposts such as New York City and Los Angeles, before going back home, perhaps, as in this novel, to furnish Tel Aviv boutiques with dark and dirty gourmet olives.

Procuring these special olives necessitates going into business with Arab olive growers whose view of their Jewish partners is one of the many sources of humor in this expansive, ambitious novel. One olive grower breathes a sigh of relief when the Jews nearby are “quiet and focused on their holidays.” His son, though, remains on guard against a Jewish partner, until “learning he wasn’t a real settler, wasn’t a religious lunatic, that all he intended was for everyone to profit from the [olive] initiative … [and] gave him a pass.”

The word “hilltop” in today’s Hebrew connotes West Bank settlement. And though Ma’aleh Hermesh C., the settlement at the center of this book, is sustained as much by fumbling misadventure as by intention, it is nevertheless an illegal settlement whose very existence is a bone of ongoing, if often comedic, contention.

• Look Who’s Back by Timur Vermes (translated from German by Jamie Bulloch)

This novel, a huge hit in Germany, is about Hitler waking up in today’s Berlin and wondering what happened. Why, for example does he have such a ferocious headache? Might it be due to his blowing his brains out as the Allies closed in on his Reich Chancellery? And where are Eva Braun, Goebbels, Goering, Himmler, and the other worthies? Can they be expected to wake up, too, so all that fun could start again?

It’s an interesting conceit to put the Fuhrer in situations where his disorientation, obstinacy, and seeming authenticity bring him cheers, jeers, and a hit television show. But when Hitler 2.0 decides to run for office under the slogan “It wasn’t all bad” the humor that had just barely sustained the conceit dries up.

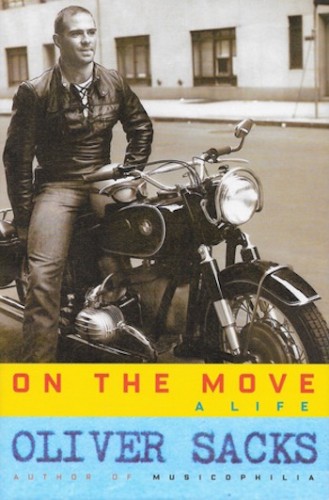

• On the Move: A Life by Oliver Sacks

The author of this captivating memoir should need no introduction: he is the man who replaced Freud as our culture’s most necessary storyteller about mind, brain, and character. The sad thing about the book is that it is the author’s last, barring posthumous collections: Sacks died in August, 2015.

In On the Move we learn about Sacks’s homosexuality, his Jewishness, the motorcycles he has coveted and ridden, his weightlifting feats at Muscle Beach in California, his meetings with remarkable men and women, from Francis Crick to Mae West. No small part of this volume’s appeal are its photos, depicting Sacks bench pressing 600 lbs and gunning his motorcycle to 100 mph. Who knew this about the ever moving Dr. Sacks? (My interview with Sacks.)

• Days of Rage: America’s Radical Underground, the FBI, and the First Age of Terror by Bryan Burrough

This is about the time — 1960’s through ’70s — when religious extremists hadn’t yet adapted the theory and practice of terrorism to their own apocalyptic designs. Burrough finds that that there was no lack of apocalyptic fervor in the Marxist-Leninist-Maoist-Fanonist secular left.

Burrough takes an encyclopedic approach, compiling testimony from a range of sources, many of whom had, until speaking to him, remained silent about their political pasts. The results are by turns dull and revealing. No one puts the two ages of terror — secular and religious — together better than the late activist and lawyer Elizabeth Fink, who told Burrough:

You have to understand, the underground, it became a cult. . . [Weatherman] was a cult. The SLA. The sixties drove them all crazy, all of us. All they did was listen to their own people, their own opinions. by ’74, ’75, when the war was over, you should have said, you know, ‘What the fuck? The revolution isn’t happening.’ But they were crazy. I was part of that craziness. I know this to be true. It’s just like the Middle East today, Al Qaeda, a lot of crazy people doing all this very bad shit.

• The Mantle of Command: FDR at War, 1941-1942 by Nigel Hamilton

Hamilton aims to give FDR credit he has long been denied for his leadership in the early days of the war. Roosevelt had to avoid a premature landing in France, where Hitler had at least twenty-five divisions waiting for untested American troops. At the same time, he had to keep Churchill’s attention on the war in Europe once a German invasion of England was no longer an imminent threat. Churchill seemed worried most of all about preserving the British Empire.

FDR oversaw the rapid transformation of American armed forces, a “tiny professional army — seventeenth in the world ranks in 1939, behind Romania — into the worlds’ most powerful potential army-air force in 1942: its numbers slated to reach 7,500,000 by the end of the year.”

And he resolved, against much opposition, that the first battleground in the American war against Hitler would be North Africa, which would pose a threat to Germany from the south.

• The Odd Woman and the City by Vivian Gornick

Friendships, loneliness, human connections, both trivial and profound in New York City: these are the themes to which Gornick returns in this, her latest memoir. She is endlessly perceptive about literature as well as people, and can be unnervingly funny:

At three in the afternoon, I pass a man who is yelling in the air, “Help me! Help me! I’ve got four uncurable diseases! Help me!” I tap him on the shoulder and cheerfully confide, “The word is incurable.” Without missing a beat, he replies, “Who the fuck asked you.”

• The Cartel by Don Winslow

• The Cartel by Don Winslow

This novel does not spare the reader details of the colossal, numbing brutality of the war on drugs, which is equaled in scale only by its futility.

DEA operative Art Keller, the book’s main character, reflects that:

He’s been in Mexico — just on this last incarnation— longer than the U.S. was in World War II. When you ask people, “What’s America’s longest war?” they usually answer “Vietnam” or amend to that “Afghanistan,” but it’s neither.

America’s longest war is the war on drugs.

Forty years and counting, Keller thinks. I was here when it was declared and I’m still here. And drugs are more plentiful, more potent, and less expensive than ever.

• Killing a King: The Assassination of Yitzhak Rabin and the Remaking of Israel by Daniel Ephron

The assassination of Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin in 1995 by right-wing Jewish extremist Yigal Amir was of decisive historic importance, probably the greatest single blow to a peace process that seemed capable of success when Rabin shook hands with Yassir Arafat on the White House lawn on September 13, 1993.

To quote from my review of this compelling book:

Amir was not a lone gunman in the sense that we, in the United States, apply that term to Lee Harvey Oswald. True, it was Amir, and only Amir, who fired the gun, though conspiracy theories claiming otherwise, of necessity, arose. But Amir had a sizable, coherent and enduring, even swelling, portion of Israeli public and clerical opinion behind him when he struck, as Oswald did not. Oswald was a lonelier lone gunman, by far. Well-known rabbis furnished Amir with esoteric, and finally, nonsensical Talmudic rationales for killing Israel’s duly elected leader.

• Make Me by Lee Child

Lee Child’s Jack Reacher novels are suspenseful, but as with so many entries in the mystery genre tend to become formulaic.

Reacher, six-foot-six, ex-military police, hitches, takes buses or trains around the country with nothing but a tooth brush and a few bucks. He does not tarry for laundry; when his shirt and jeans fray or get bloody, he trashes them and gets new ones. Reacher has a Dean Moriarty, on-the-road kind of charisma, but with proficiency in hand-to-hand combat and weaponry thrown in. Child’s depiction of Reacher’s many and varied pitched battles work well; it’s Reacher’s nova bursts of intellectual superpower that can be trying. They put everyone else in the cast of characters assembled around him in the shade. They are only around to spotlight his brain

What nevertheless recommends Make Me is its setting — the Deep Web. As one character depicts this subterranean strata of the Internet:

…one imagines pornography of the most unpleasant sort, or mail-order cocaine, and so forth. . . . The Deep Web might be ten times bigger than the Surface Web. Or a hundred. No one knows. How could they? Not to be confused with the Dark Web, of course, which is merely out-of-date sites with broken links.

Reacher happens on one particularly sickening node of the Deep Web when he gets off the train in an isolated Midwest town called Mother’s Rest.

— Harvey Blume

Harvey Blume is an author—Ota Benga: The Pygmy At The Zoo—who has published essays, reviews, and interviews widely, in The New York Times, Boston Globe, Agni, The American Prospect, and The Forward, among other venues. His blog in progress, which will archive that material and be a platform for new, is here. He contributes regularly to The Arts Fuse, and wants to help it continue to grow into a critical voice to be reckoned with.

Here are some books worth reading and buying that I discovered in 2015. Some I reviewed and some I did not.

* On The Move – Oliver Sacks

A terrific memoir, filled with all kinds of unforgettable detail about Sacks’s early, very lonely life. I was struck by his indomitable spirit as he tackled not only personal issues but also work issues. His quirky and mind sometimes led him into trouble, but more often it found paths that were truly original and endlessly fascinating. Just knowing he was doing his amazing work was a comfort to me for many years; now that he is, sadly, gone, but, we must cherish his important body of work and make sure the next generation knows about them.

* When the Facts Change – Tony Judt

This posthumous book of essays by the great historian Tony Judt with a wonderful, revealing introduction by his wife, Jennifer Homans. This is a fine addition to any library that includes Judt’s work. Intelligent and thoughtful, it probes issues that are relevant today. However, it is not the best introduction to this writer — for that I would suggest The Memory Chalet or his masterpiece of historical writing, Postwar.

* Death By Water – Kenzaburo Oe, translated by Deborah Boliver Boehm

A valedictory narrative by the great Japanese Nobel Prize winner. Oe’s brilliance, enhanced by this very accessible translation, is on full display here. A complicated novel that goes beyond the author’s usual preoccupation with family ties and raises questions of what is art and how one makes it. A book that takes interesting risks and will fascinate anyone interested in modern fiction.

* Thirteen Ways of Looking – Colum McCann

McCann’s work can be uneven, and although most people loved Let the Great World Spin, I much preferred his Transatlantic. In his latest book, a novella and a few other stories, he has given us a superb story “Sh’kol,” just nominated to be included in The Best American Stories, as well as the title novella which reminded me of Saul Bellow, high praise, indeed.

* The Given Day, Live By Night, The World Gone By — a trilogy by Dennis Lehane

These three books, the last of which was published this year, comprise a wonderful American saga about the Coughlin family of Boston that deserves a wide readership. Lehane is known as a master of mystery, but in these books, especially the first, he has gone beyond that genre and written a volume so American and so good it should have gotten a Pulitzer. It has drama and amazing characters, a vivid Boston setting and uses 20th century history in a way that is as compelling as anything I have read in a long time. All in vivid, precise prose that is a pleasure to read.

* Academy Street – Mary Costello

A first novel by a young Irish writer, also the author of a story collection called China Factory, who has talent to spare. In this short novel she has given voice to Tess Lohan, whose ordinary, yet remarkable life is often lost both in fiction and in real life. But here Costello tells the story of a prosaic character with compassion and grace. In the end, Tess’s fate becomes the fate of all of us who have lived to witness the violent beginning of the 21st Century. At her best she reminds me of her Irish compatriots, William Trevor and Elizabeth Bowen.

* Erebus – Jane Summer

For those looking for something unique here is a poem that is far more than a poem, an investigation of an air crash in Antarctica told in prose, poetry, graphics, and news reports that plumbs the deepest emotions without a trace of sentimentality. A marvelous hybrid by a writer who is also the author of The Silk Road and from whom we shall surely hear more.

* A Brief Stop on the Road From Auschwitz – Goran Rosenberg, translated by Sarah Death

A beautiful memoir about how families cope after an event like the Holocaust. The recent publication of the oeuvre of Primo Levi is proof of how important this book by Rosenberg is. His story is of his father, David, who did everything right after the war, but who could not find a place for himself in the world after all that he had witnessed. Enormously moving and important — should be in every public or private Holocaust library.

* Peggy Guggenheim – Francine Prose

Although this biography could have been a lot better than it is, this volume in the Yale Series of Jewish Lives is chock full of interesting information about one of the great “characters” of the 20th century, the art collector Peggy Guggenheim. Born to great wealth she had many burdens and many quirks, but her life is fascinating and, while her behavior was often extreme, her story is important, representative of how a woman with vision in the 20th century had to struggle to leave her mark.

* Girl of My Dreams – Peter Davis

An ambitious novel that looks like your typical Hollywood yarn, but turns into something much more interesting and compelling. At first the prose is a little unsteady. Persist, and you will be rewarded with surprises in the characters and plot. The California setting is very well done. The narrative would be a great movie, which fits, because Davis was the director of the great documentary Hearts & Minds.

— Roberta Silman

Roberta Silman‘s three novels—Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again—have been distributed by Open Road as ebooks, books on demand, and are now on audible.com. She has also written the short story collection, Blood Relations, and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. A recipient of Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships, she has published reviews in The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for The Arts Fuse. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Seven Best Books of 2015. (And Three Overrated.)

Best Books:

* Submission by Michel Houellebecq

The most important novel of the year. A witty, melancholy, provocative analysis of the pressures and counter-pressures battling it out just under the surface in present-day France—fast-forwarded to the future. Published on the day of the Charlie Hebdo killings. Let us hope not as prescient as it may be about the upcoming (2017) French presidential elections. But certain signs point that way…

* Look Who’s Back by Timor Vermes

It’s a happy surprise to see this novel doing well in the States, given the arguably tasteless subject matter (namely, the return here and now of our Adolf) and the rollicking take-no-prisoners humor about present-day German society, its hang-ups, obsessions and hypocrasies. I burst out laughing every few pages. A nice holiday gift to pair with Submission, for doomsday cynics?

* The Buried Giant by Kazuo Ishiguro

How many degrees can a writer turn in a lifetime? Surely more than 360 in Mr. Ishiguro’s case. Like all writers destined to become classics, he is constant only in his originality. From the restrained, precocious melancholy of The Remains of the Day through the much-misunderstood historical mirroring of When We Were Orphans, and the distopia of Never Let Me Go—now he offers a fabulous road-story for our times, set in post-Arthurian Britain. On the one hand a delicate meditation on long love and on the loss of memory, both individual and collective. On the other, hard insights into the roots of human warfare and revenge-seeking, unchanged since that semi-mythical age.

* The Automobile Club of Egypt by Alaa Al Aswany

Another of Aswany’s wry, humane, and ultimately (almost always) forgiving investigations into human desires, pride and follies. To enter the world he portrays is to understand the complexities of Egyptian society and culture from the inside, in a way a hundred academic articles could never do. Not to mention that Aswany’s novels are impossible to put down!

* The Love Object by Edna O’Brien

Anything by the beautiful, wayward mind of Edna O’Brien is better than most anything else published in any given year. These short stories are a good place to begin to know her, or continue to be surprised. No one unveils the intricacies and urgencies of female friendship better. Take that, Elena Ferrante, and take your clichés elsewhere.

* All The Old Knives by Olen Steinhauer

The ever-modest author (disclosure: he’s a friend of mine) might demur, saying ‘thanks, but hardly a ‘Best Book.’ The genre is spy thriller, the settings Vienna and Lotus-land, and Steinhauer delivers fine entertainment as always, gripping, intelligent, politically impeccably informed. All the Old Knives will keep you guessing (in vain) as it drives to a close with rising stakes, sparkling wit and genuine sympathy for the fateful weaknesses of its plot-entangled characters.

* Negroland by Margo Jefferson

The clarity and thoroughness of recollection in this memoir is refreshing and unflinching. Plenty of food for nostalgia here, both sweet and bitter, for a certain American way of life never before given such voice: that of being a middle-class black girl, mid-century. Sometimes the taboo subjects are right out in plain sight. Jefferson’s book is not only wonderfully readable, it is also a sociological landmark.

***

Overrated:

* Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehesi Coates

Message from the Howard University grad and star Atlantic journalist to his fourteen-year-old son: blacks are ever victims, whites the exploiters, and we all are prisoners in racially defined cages, incapable of ever moving toward empathy or mutual understanding.

* Purity by Jonathan Franzen

Literary devices, willful obscurities, and sheer wordiness. Easy to put down.

* My Brilliant Friend by Elena Ferrante

Another of this author’s lessons in how to push stereotypes around to make a rather soapy story—perhaps the very key to bestsellerdom.

— Kai Maristed

Kai Maristed studied political philosophy in Germany, and now lives in Paris and Massachusetts. She has reviewed for the Los Angeles Times, the New York Times, and other publications. Her books include the short story collection Belong to Me, and Broken Ground, a novel set in Berlin. Read her Paris-centric take on politics and the arts here.

Tagged: Assaf Gavron, Days of Rage: America's Radical Underground, Death by Water, Harvey Blume, Look Who's Back, Oliver Sacks, On the Move: A Life, Roberta Silman, The Hilltop: A Novel, The Sympathizer, Thirteen Ways of Looking, Viet Thanh Nguyen, and the First Age of Terror, the FBI