Book Review: “Days of Rage” — Counterculture Craziness

How can you act sanely when your country is brazenly committing genocide? Many of us didn’t.

Days of Rage: America’s Radical Underground, the FBI, and the First Age of Terror by Bryan Burrough. Penguin Press, 608 pages, $29.95.

By Harvey Blume

It’s not easy, for those who weren’t there and perhaps even for many, like me, who were, to think yourself back to a time when slogans like “DEATH TO THE FASCIST INSECT THAT PREYS UPON THE LIFE OF THE PEOPLE!” made any sense whatsoever. That, in case you’ve forgotten, was the slogan of the Symbionese Liberation Army (SLA), notorious for the kidnapping of Patty Hearst. True, even back then, that slogan struck many people as a mite peculiar. It occurred to many that the SLA was everything nutty about the rest of us distilled into a single group, as in the SLA was crazy, we were not. But it’s also possible to read the tale told in Days of Rage differently and entertain the notion, however fleetingly, that we, the rest of us, might be described as SLA lite.

Nor, thinking back, is it easy to imagine that members of Weatherman, no doubt the best known and most documented of the groups covered in this book, would adopt the Maoist practice of “criticism/self-criticism, essentially a marathon all-night interrogation in which members were accused of very conceivable human weakness.” The goal of grueling crit/self crit was to eradicate individuality, so as to create soldiers of a Red Army, who would be to Amerika what the NLF and the Viet Cong were to the war in Vietnam.

Nutty, huh? Completely and absolutely nutty, for sure. What gives the nuttiness essential context, though, is that city after city in the United States was going up in flames; that leader after leader with any genuine authority was being murdered (JFK, RFK, MLK, Malcolm); and above all, that the war in Vietnam was being waged.

It has been said, of Germans suffering the hyperinflation of the Weimar period that if a loaf of bread cost a billion marks in the morning and two million in the afternoon then even the nonsense spouted by such a schmuck as Hitler might help explain things. For people of my generation, it went like this: if the cold-blooded murder of innocents at My Lai was how the United States waged the war in Vietnam — in which, let’s not forget, the likes of me were expected to serve — then, forgive me, but Mao looked good.

We knew My Lai was not an isolated incident. We knew in our bones that the carpet bombing of Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam was pure and simple genocide.

How you act sanely when your country is brazenly committing genocide? Many of us didn’t.

Burrough has been accused by critics of not providing enough political background to his material. And it is true his book can read like one damn bombing after another, one group after another succumbing to the FBI, idiocy or exhaustion. But now and again the bomb squad procedural does give way to passages like this:

The revolution — a single global uprising of the “oppressed” — was happening, right now, all over the world, and would soon come to America. It was an idea that seemed to wash over the Movement in a matter of minutes, easy to discuss, harder to grasp, harder still to actually believe. Yet it spread with stunning swiftness.

He’s got that right. Even not counting the effect of hallucinogens it could feel just like that.

And he’s right when he points out that:

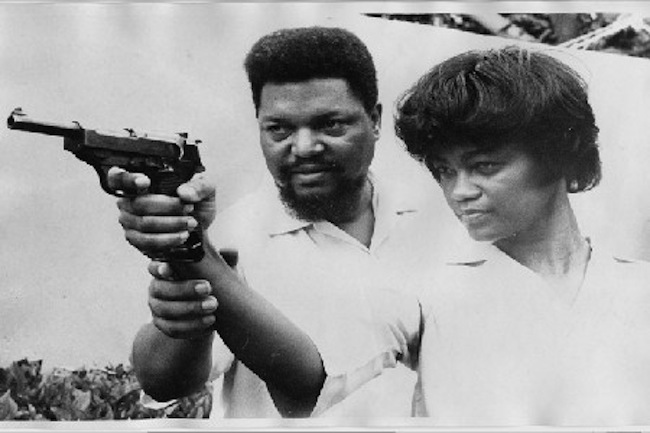

Both [Bobby Seale and Huey Newton, founders of the Black Panther Party] were smitten by the entire canon of revolutionary literature circa 1966, especially Negroes with Guns, Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth, and anything by Che Guevara. They read everything Mao wrote.

Who could resist that exquisite corpus of writing?

Back then.

“Negros with Guns” author Robert F. Williams and his wife Mabel.

One reviewer of Days of Rage described it as “riveting and dull.” I can’t improve on that. I’d also say there are stories in this book that stand out and merit continued attention. Though much of Weatherman has been mined in memoir or in fiction, some rich source material remains. For example, there is the scene in the West Village townhouse, adjacent to Dustin Hoffman’s place, and shortly to be blown to pieces, with three people dead. The Weathermen are putting together a bomb to be delivered to an officer’s ball at Fort Dix, where, if the device had gone off as intended, not only officers but women and children would have been slaughtered.

Burrough records:

There was, however, at least one naysayer [to this plan]. He will be called James.. . . James was a member of the collective who did not live in the townhouse. According to a longtime friend, “the target had been bothering him for days. Finally, right a the end, he went nuts. This was the night before. He just went crazy, crying and screaming, ‘What are we doing? What are we doing?’ And you know what Teddy Gold told him? [He said] ‘James you have been my best friend for ten years. But you gotta calm down. I wouldn’t want to have to kill you.’ And he was serious.”

Burrough is not the first to record this interchange. Mark Rudd does so in his memoir Underground: My Life In SDS and the Weathermen. I keep coming back to the event. Ted Gold had been a friend of mine. But had that bomb he was working on gone off on at Fort Dix, the anti-war movement would have been crushed by martial law, and god help the Vietnamese.

As I say, it’s hard to recall that time and place, its peculiar odors and imperatives. My copy of this book, I must say, came with a useful mnemonic: a vial of tear gas. One whiff brings it all back. If your book is tear gas free, let me leave you with this statement by Liz Fink, a lawyer who was both a defense attorney and a co-conspirator in many of the events described.

You have to understand, the underground, it became a cult. . . Weather, it was a cult. The SLA. The sixties drove them all crazy, all of us. All they did was listen to their own people, their own opinions. by ’74, ’75, when the war was over, you should have said, you know, ‘What the fuck? The revolution isn’t happening.’ But they were crazy. I was part of that craziness. I know this to be true. It’s just like the Middle East today, Al Qaeda, a lot of crazy people doing all this very bad shit.

Plenty to think about there.

Harvey Blume is an author — Ota Benga: The Pygmy At The Zoo — who has published essays, reviews, and interviews widely, in The New York Times, Boston Globe, Agni, The American Prospect, and The Forward, among other venues. His blog in progress, which will archive that material and be a platform for new, is here. He contributes regularly to The Arts Fuse and wants to help it continue to grow into a critical voice to be reckoned with.

Tagged: America's Radical Underground, Black Panthers, Bryan Burrough, Days of Rage, Symbionese Liberation Army, Terrorism

I recommend Carl Oglesby’s sadly overlooked memoir of the era, Ravens in the Storm: A Personal History of the 1960s Anti-War Movement as a complementary read to this book. He makes a strong case that leftism did not have to go off the rails the way it did. Extremism is a dangerous seducer.