Book Review: “Peggy Guggenheim, The Shock of the Modern” — The Woman Behind a Remarkable Legacy

Although there is a strangely dour tinge to this biography of Peggy Guggenheim, Francine Prose is ultimately fair.

Peggy Guggenheim, The Shock of the Modern, by Francine Prose. Yale University Press, 211 pages, $25.

By Roberta Silman

Sometimes a chronological tale has the most dramatic impact. That was what I kept feeling all through the first half of this biography, one in the series of Jewish Lives published by Yale University Press. But instead of starting with Peggy Guggenheim’s childhood and youth, Francine Prose begins her handy, serviceable book with a description of the Peggy Guggenheim Museum at the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni on the Grand Canal, which holds Peggy’s remarkable legacy to the world — her collection of painting and sculpture of the 20th century.

And then we are thrust into the midst of her collecting — first in Paris before the Second World War, her short-lived foray into the art world of London, and then in America, where she and her collection were ensconced during the war at a stunning home on 57th Street which she called Art of This Century. Only after the war did she realize that her passion for art and her talent for collecting should be given a home somewhere in Europe where it would last, hopefully, forever.

Along the way we are treated to an inordinate amount of gossip about Peggy’s bad choices in men, her troubles with her first husband Laurence Vail and his new wife Kay Boyle, her battles with them about Sinbad and Pegeen, the children she had with Vail, her voracious appetite for sex, which seemed to keep her in constant trouble, her marriage to the fey John Holmes, her intense affair with Samuel Beckett, and her inability to resist the cruel Max Ernst, who used her and her money to help him get out of Europe and then married her, thus entering into a complicated relationship with her daughter Pegeen whom, it is hinted, he may have molested. We learn about the homes Peggy made in both England and New York and her need to help artists and writers who loved her largesse but who had no compunctions about bad-mouthing her and her stinginess, which is often a characteristic of the very rich, who sometimes don’t know how much money they have and are wary of being conned.

There is a lot of name-dropping in this book, so much that I sometimes felt it was a veneer for what could have been a more interesting and insightful biography about a woman who had had a very difficult childhood and youth and who overcame what seemed to me were enormous obstacles.

A granddaughter of Meyer Guggenheim, who bought a Colorado silver mine in the late 19th century and parlayed it into legendary riches, Peggy Guggenheim was born in 1898 to Meyer’s fifth son, Benjamin, and Florette Seligman, whose German Jewish family were bankers, far richer than the Guggenheims. Peggy was the middle of three daughters, the plainest of the three, as she was told again and again by her mother who had a strange disorder, perhaps a form of Tourette’s syndrome, that forced her to say everything three times. Benjamin was a renegade who did not go into the family business and marched to his own drum. Although Peggy was aware quite early that her parents’ marriage was far from perfect, she adored her father, and one of the few really moving passages in this book is a description of how Benjamin would come home whistling a special tune that brought Peggy running to him from wherever she was in the large and lavish house.

However, when she was fourteen her father simply disappeared: on a trip home from Paris with his mistress he made the mistake of booking on the new Titanic. After Benjamin’s untimely death, Florette was helped by his brothers, who were determined to help her maintain “the Guggenheim lifestyle.” But apparently she thought she could take better control of her life and retrenched a little. This last is important because Peggy knew what it was to meet adversity and live without a man from a very early age, even though Prose keeps insisting that one of Peggy’s great flaws was that she needed a man to guide her and love her and, it often seems, abuse her.

From the time of her father’s death which she claimed — reasonably — that she never got over, Peggy seems to have grappled with a debilitating sense of inferiority, a part of her personality she was unable to shake. She hated her appearance, especially her nose, and even tried to have it fixed in her early 20s but the operation was not a success. (In photographs it doesn’t look so bad to me, although her excessive drinking may have made it swell at times.) And although she was a good reader by the time she was a teenager and attended the prestigious Jacoby School for Girls in Manhattan, she had to drop out because of illness and was persuaded not to go to college by her older sister Benita, whom she adored. Instead, Peggy depended on private teachers and friends like Lucille Kohn — and later Emma Goldman — to encourage her intellectually. They also convinced Peggy “that people like the Guggenheims had an obligation to change the world for the better.”

A lucky break was getting a job in her early 20s in a bookstore called the Sunwise Turn near Grand Central, where she came under the influence of Madge Jenison, whose vision of a place where intellectuals could gather would come to fruition decades later when Peggy started her own galleries. But before that there would be a succession of family tragedies: her sister Benita died in childbirth, her cousin John Simon (in whose memory the famous Guggenheim Foundation was founded) died at seventeen of mastoiditis, her sister Hazel’s sons somehow fell from a balcony and died when very young, calling into question Hazel’s sanity, and a few years later John Simon’s brother committed suicide and Florette died. All this before Peggy turned 40. Although Florette’s death gave her even more money to spend on the art she was beginning to love, Peggy had already brought on herself other tragedies because of her extreme neediness, which took the form of nymphomania and a preoccupation with sex that was truly bizarre and makes for somewhat uncomfortable reading.

That may be the clue that something was missing in Peggy, or it could have been an added burden. But it is clear that, although outgoing, Peggy could also be guarded and imperious and, at times — most important — she seemed to lack any kind of moral compass. Prose tells us twice that on the day the Nazis invaded Norway Peggy was negotiating a sale with Fernand Léger, who was Jewish and could not believe her crassness. Armed with a list from Herbert Read and advice from Marcel Duchamp and accompanied by another advisor named Howard Putzel, she had decided to buy a painting a day, and damned near did, until it became clear even to Peggy that she, an American Jew, would have to get herself and her family and her collection out of Europe as soon as possible.

Still, she never seemed solidly grounded in the world. Here is a passage about Peggy while she was still in Europe:

The pleasure Peggy took in the company of the unspoiled M. and Mme Tanguy did not stop her from seducing the painter. Though Peggy could be extremely possessive, she never seemed to feel there was anything reprehensible about sleeping with other women’s lovers and husbands. Not long before her affair with Tanguy, she had had a quick romance with Giorgio Joyce [James Joyce’s son], whose wife Helen, had been Peggy’s friend since Peggy worked at the Sunwise Turn in New York, and who — at the time Peggy slept with Giorgio — was in the hospital, having suffered a nervous breakdown.

This was symptomatic of one of Peggy’s most serious character flaws: a certain lack of empathy that kept her from understanding that others … might not feel the way she wished them to feel. Coupled with a certain inability to deny herself anything she wanted — be it a new painting, or a new man — this trait led her to fail the people she loved in ways that seem far more problematic than the flaws of which she was more often accused: promiscuity, shallowness, stinginess, and a sense of humor that sometimes crossed over into malice.

Yet she was saved from being another rich, sexy dilettante by her passion for art. Once she had read her way through Bernard Berenson in her late 20s and absorbed as much about modern art as she could throughout her 30s and 40s, she became as obsessive about art as about sex. Her collecting took over her life. She would say, “I am not an art collector, I am a museum.” And once she developed the dream of what did become the Peggy Guggenheim museum, the art became more important to her than anything, even her troubled children, one of whom — Pegeen — would commit suicide in the 1960s.

Coming back to America during the war forced her to mature, and as she did, you can see Prose warming to her. Here is a salient passage about her ability to learn and listen in her New York gallery during the war as told by Jimmy Ernst, Max Ernst’s son by an earlier marriage:

Peggy joined Mondrian, who stood rooted in front of the Pollocks. “Pretty awful, isn’t it? That’s not painting, is it?” [Peggy asked.] When Mondrian did not respond, she walked away. Twenty minutes later he was still studying the same paintings, his right hand thoughtfully stroking his chin. Peggy talked to him again. “There is absolutely no discipline at all. This young man has serious problems . . . and painting is one of them . . .” Mondrian continued to stare at the Pollocks, but then turned to her. “Peggy, I don’t know, I have a feeling that this may be the most exciting painting that I have seen in a long time, here or in Europe.”

Earlier Prose had given us a passage from the memoir, A Not-So-Still Life, by Jimmy, who worked for a while for Peggy in New York:

To Jimmy, Peggy’s shyness and lack of affectation suggested a painful past. At the same time there were flashes of brilliance, charm, and a warmth that seemed to be in constant doubt of being reciprocated. It must have been the anticipation of such rejection that caused her abruptly changing moods, penetrating retorts and caustic snap judgments, but never at the cost of her femininity.

Clearly there was something indefinable about Peggy that endeared certain people to her for life. Although she has not gotten good press, especially in the most recent biography about her by Anton Gill, and although there is a strangely dour tinge to this present biography, especially in the unfortunate early chapters entitled “Her Nose” and “Her Money,” Prose is ultimately fair. As one of her epigraphs, she quotes Lee Krasner:

In writing about Peggy it’s important to listen to one’s own instinct. Don’t listen to critics. What do they know? What one should say about Peggy is, simply, that she did it. That no matter what her motivations were, she did it.

That is high praise from Pollock’s widow. Although Peggy became a real fan of Pollock’s work, especially the “poured” paintings which she fostered early in his career by giving him a stipend and a contract and making it possible for him and Krasner to buy a home in Springs in East Hampton, Peggy dismissed Krasner’s work quite cruelly.

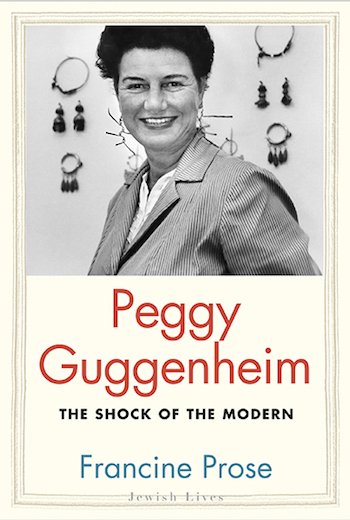

Peggy Guggenheim in 1967. Photo: Ron Galella.

So, we are left with an enigma, and only at the end of this short book do we see Prose searching for the answers. She is talking to Philip Rylands, the present director of Peggy’s Venice museum, who tells us:

She was fascinated by people and how they interacted. That was part of the reason why she had the most international salon in Venice. Part of her zest for human interaction was about her desire to really get to know other people. She was never banal, never said anything that seemed like a cliché. When she spoke it was a direct expression of her thoughts, and she thought a great deal. She did have the rich person’s fear of being taken advantage of, but she was generous — generous to her children and grandchildren and to artists and writers she supported and admired.

It is a good way to end this book.

“La Peggy,” as they called her in Venice, was a force, a Jewish woman a decade older than my own mother and mother-in-law, who, despite all kinds of obstacles, made a mark on the 20th century that will last as long as Venice lasts. As I read I found myself wishing that I had had the nerve when young, as John Guare did, to knock on her door at the Palazzo in Venice. When a woman in a bathrobe opened the door and showed him around, taking her time with each painting and sculpture, he asked if she worked there. And was astonished when she said, simply, “I am Peggy Guggenheim.” This incident speaks volumes and opens a door that maybe a future biographer will take, finding the real Peggy and linking the older, surer Peggy to the vulnerable girl who was deprived of so much when she was still so young.

Roberta Silman Her three novels — Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again — have been distributed by Open Road as ebooks, books on demand, and are now on audible.com. She has also written short story collection, Blood Relations, and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. A recipient of Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships, she has published reviews in The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for Arts Fuse. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Tagged: Francine Prose, Jewish Lives, Peggy Guggenheim, The Shock of the Modern