Book Review: Bill Griffith’s Indelible “Invisible Ink”

Bill Griffith, the creator of Zippy the Pinhead, dives deep into his personal life in his extraordinary new graphic memoir.

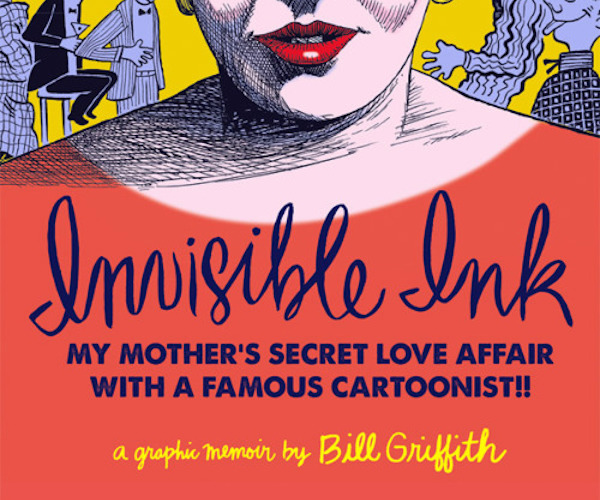

Invisible Ink: My Mother’s Secret Love Affair with a Famous Cartoonist!! by Bill Griffith. Fantagraphics Books, 208 pages, $29.99.

By Betsy Sherman

Having read about three decades’ worth of Zippy the Pinhead, I feel a certain intimacy with the daily comic strip’s creator, Bill Griffith. After all, he inserts a version of himself, Griffy, as the opinionated second banana to the muu-muu-wearing hero, and there’s an ongoing ego-id dialogue between the two. Griffith occasionally writes “Random Memory” entries that offer vignettes from his childhood in Long Island’s Levittown or from his days in the underground comics movement. He’s also offered tributes to heroes from Alfred Jarry to Arnold Stang.

Griffith goes deeper into his personal life in his extraordinary new graphic memoir Invisible Ink: My Mother’s Secret Love Affair with a Famous Cartoonist. The core subject is, as the subtitle promises, the 16-year adulterous affair between his late mother, Barbara, and the man for whom she worked as a secretary, cartoonist/pulp novelist Lawrence Lariar.

Barbara was a child of the Depression who didn’t have the means to go to college, as she had wished. While working at an office in Manhattan, she met and married James Griffith, a co-worker. In the 1940s, during much of which James was away in military service, the couple had son Bill and daughter Nancy. The family lived in Brooklyn, then moved to the mother of all suburbs, Long Island’s Levittown. Although her trajectory was somewhat typical, Barbara’s lineage wasn’t: her grandfather was a pioneering photographer of the Old West, William Henry Jackson.

The intellectually curious Barbara, who had literary ambitions, soon tired of the “paradise” of the suburbs. Her husband was rigid and repressed. In spite of James’s objection, she answered an ad for a part-time secretarial job for a Manhattan-based cartoonist. Lariar, too, was married. Barbara succumbed to his seduction and the two carried on a physical relationship complemented by a shared passion for art and literature. Their clandestine meetings took place in the vibrant Manhattan of the beatnik era, stretching from the late ‘50s into the ‘60s.

Barbara confessed the affair to Bill and Nancy directly after James’s death in 1972 from a head injury suffered in a bicycle accident. Neither asked for the gory details while their mother was alive, and it wasn’t until years after her death in 1998 that Bill delved into the extensive papers she left behind. These included her diaries, poems, scrapbooks, and an unpublished roman à clef about an unhappily married woman who has a secret lover. Griffith draws from the novel in order to help flesh out the couple’s story.

Griffith’s creation is so much more than an anecdotal telling of this family “skeleton.” While it is primarily the narrative and graphic portrait of a family—his mother’s background is well documented by stories and photographs, his taciturn father is much more mysterious—it’s also a piquantly illustrated history of urban and suburban New York mid-20th century, a history of the comic book industry, and a detective story set in archives both institutional and housebound. Not incidentally, it’s a loving eulogy for an imperfect woman of irrepressible spirit who did not settle into middle age (“I knew Mom was no June Cleaver,” writes her son).

The book is suspenseful, but Griffith, as our guide, leavens the suspense with his own ruminations as a son who may regret treading into taboo areas. With the graphic format, we get to read not only Griffith’s words but also the expressions on the face of Griffy as child, teen, and adult. The drawings posit times he may have come close to crossing paths with his mother and Lariar. He’s a 14-year-old in his motorboat while the pair is in Guy Lombardo’s waterfront restaurant, a stone’s throw away. Later, he treks to Greenwich Village to see Allen Ginsberg on the same night Barbara and Larry are taking in a Pete Seeger concert there. There’s a Freudian frisson when Griffith is going through the Lawrence Lariar Collection at Syracuse University (sadly, he’s the first scholar to do so): a photo of the man has lipstick traces on it. Er, Mom? Griffith teases with a soap-opera touch now and then—his mother, after all, had some stories published in True Confession-type magazines—but he makes the love scenes believable in a way that’s touching.

The story has wonderful bookends as Griffith pays two visits to Uncle Al, his mother’s younger brother, in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Zippy readers well know of Griffith’s ambivalence about digital technology, so it’s no surprise when he’s overjoyed about Al’s gift of his old drafting supplies. But this Griffy is equally pleased that with his laptop he can share with the computer-less Al the abundance of information on the Web about Al’s photographer/painter grandfather, “WHJ.”

Griffith, through his beautifully detailed artwork, has a sort of dialogue with the man who could have become his stepfather, had fate twisted a certain way (a subject of contention might have been cross-hatching, which Lariar hated but is an integral feature of Griffith’s technique). The old-timer cooked up dozens of comic strip characters, in varying styles and genres, looking to score the holy grail of a syndication deal. He was a prolific creator of gags for humor magazines (corny stuff, for sure), and published best-of compilations and how-to books. Griffith recreates strips drawn by Lariar and some of his peers, and imagines using Lariar’s “Peanut System” (body components being in the shape of the unshelled nuts) for Zippy and Mr. Toad. Visual rendering makes the many flashbacks robust, with period fashions, architecture, advertising, and a cameo by the actor Stubby Kaye helping to fill out the scenes.

There are laughs in this memoir, but its moods extend into the melancholy. At one point, Barbara is alone on a 42nd Street subway platform, its bleakness reflecting her crushed feelings. However, Invisible Ink stands strong for pleasure, whether derived from satisfying one’s libido, enjoying comic books and jazz, or indulging in the home-style cafeteria food that Griffith eats in North Carolina. That said, by the story’s end this son even finds compassion for the difficult father who had a built-in “repression mechanism.” The final panels evoke the paintings of Edward Hopper and the films of Yasujiro Ozu, and hint that while some closure has been achieved, the journey to and from the past will continue.

Betsy Sherman has written about movies, old and new, for The Boston Globe, The Boston Phoenix, and The Improper Bostonian, among others. She holds a degree in archives management from Simmons Graduate School of Library and Information Science. When she grows up, she wants to be Barbara Stanwyck.