Music Commentary Series: Jazz and the Piano Concerto — The Great God George

This post is part of a multi-part Arts Fuse series examining the traditions and realities of classical piano concertos influenced by jazz. The articles are bookended by Boston Symphony Orchestra concerts: the first features one of the first classical pieces directly influenced by jazz, Darius Milhaud’s Creation of the World (February 19 – 21); the second has pianist Jean-Yves Thibaudet performing one of the core works in this repertoire, Maurice Ravel’s Concerto in G (April 23 – 28). Steve Elman’s chronology of jazz-influenced piano concertos (JIPCs) can be found here. His essays on this topic are posted on his author page. Elman welcomes your comments and suggestions at steveelman@artsfuse.org.

George Gershwin — his music and its influence show no signs of mortality.

By Steve Elman

“. . . to me it was like meeting God. Imagine the great Gershwin sitting down and playing his songs for Ethel Agnes Zimmerman, of Astoria, Long Island.” – Ethel Merman [from Ethel Merman & Pete Martin Merman, Who Could Ask for Anything More, (Doubleday, 1955), quoted in Howard Pollack, George Gershwin: His Life and Work (University of California Press, 2007]

If George Gershwin had not written Rhapsody in Blue in 1924 – if he had been another kind of musician, if he had ignored hot dance music and early jazz – there might not be jazz-influenced piano concertos. There certainly would be fewer of them.

But Rhapsody in Blue is not his greatest work for piano and orchestra. One year later, he wrote his own Piano Concerto in F, a much more ambitious and profound piece that, in my view, is his greatest “classical” work (discounting Porgy and Bess, about which there is still argument over whether it should be considered an opera or a musical).

I won’t waste your time trying to describe the Concerto in F. Go listen to it if you haven’t done so before. It makes a greater case for itself than I ever could. (See my chronology for some recommended recordings and links.)

The line of compositions that begins with Rhapsody in Blue (hereafter abbreviated as RIB) and the Concerto in F is a persistent and instructive tradition, central to the understanding of the ways in which jazz influences have entered the minds of classical composers. These two pieces opened Maurice Ravel’s ears to the use of jazz effects, and led directly to his Concerto in G, written between 1929 and 1931, a piece which (as I’ve noted previously in this series) is now one of the most popular works for piano and orchestra ever written.

Including Ravel’s concerto, there are at least 37 works for piano and orchestra by other classical composers that show Gershwin’s influence (see the list below). Seventeen were written in the fifteen years between 1925 and 1940. The other twenty come from the 74 years between 1940 and now.

By the statistics alone, it’s obvious that RIB (and the Concerto in F, to a lesser extent) had a powerful influence up to the time of World War II. Even though that influence has lessened since, it is still alive: the last work I’ve heard that shows a direct influence of Gershwin is Brent Edstrom’s Concerto No. 1 for Jazz Piano and Orchestra, written in 2007.

One factor in this disparity is marketing, plain and simple. Though Paul Whiteman probably would not have recognized the term, it was his brilliant marketing of Gershwin’s work – commissioning RIB for his orchestra, playing it in his first “Experiment in Modern Music” concert (designed to bring serious attention to jazz in the concert hall), recognizing the impact of the piece on his listeners, performing it repeatedly, touring it throughout Europe, commissioning other composers to write works in the same vein, and eventually using its principal theme as the theme for his own radio program – that put RIB into world-wide circulation. The piece captured lightning in a bottle for the listeners of the time: it signified the roaring spirit of the twenties, the expectation of a better world just around the corner, the freedom of a new moral order, the euphoric rise of the US stock market, and the tantalizing prospect of sophistication and riches for all. When Gershwin described his Piano Concerto as expressing “the young, enthusiastic spirit of American life,” he might have been talking about the symbolic value of all of his music for its contemporary listeners.

Other composers reacted to Whiteman’s marketing and the popularity of RIB – after all, who doesn’t want to have a hit? Aaron Copland composed his brilliant and innovative piano concerto a year after RIB and a few months after the premiere of the Concerto in F; despite Copland’s denials, it shows a couple of Gershwin touches, along with an understanding of the jazz of the period that is different from and deeper than Gershwin’s. Arthur Benjamin, who played RIB several times with the Whiteman Orchestra during its European tour in 1926, wrote a piano concerto immediately in the wake of that tour, in 1927. James P. Johnson paid tribute in his own way (“Yamekraw, A Negro Rhapsody,” 1927 – 28) shortly after. Whiteman himself kept the marketing going, commissioning Dana Suesse to write a Gershwin-inspired concerto for the “Experiment in Modern Music” concert in 1932.

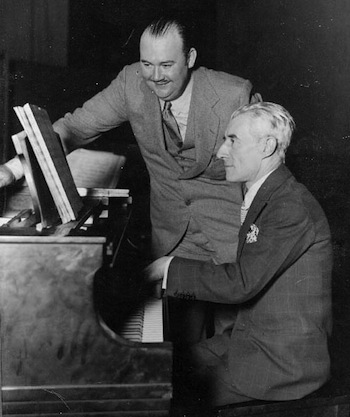

Ravel with Paul Whiteman in a publicity shot for a 1928 US tour.

Ravel met Gershwin when he visited the US in 1928, and he began sketching his Concerto in G in 1929, working on it alongside his Concerto for the Left Hand; the two works together comprise a musical Janus doubleface, wearing distinctly French spectacles. The Concerto for the Left Hand is sober and dramatic, evoking the trauma of World War I; the Concerto in G is bright and snappy, drawing on Gershwin and the spirit of post-war optimism.

Gershwin continued to have an impact on other musicians well into the Depression and for many years after his death in 1938. Some 11 concert pieces for piano and orchestra were written by other composers between 1929 and 1940, after the optimism of the twenties had evaporated. Even Bela Bartok was not immune – he met Gershwin in 1928, and his second piano concerto (1930 – 31) has one very Gershwinesque touch in the third movement: an orchestral sweep up into the flutes, followed by a percussion flourish, that’s reminiscent of a similar moment in Gershwin’s Concerto in F.

The roster of composers in the rest of the twentieth century who drew on Gershwin to a greater or lesser extent for their piano concertos includes some very big names: Benjamin Britten, in the first version of his only piano concerto, and William Schuman (both from 1938, and both among the masterpieces of the century); Gian Carlo Menotti (1948); Francis Poulenc (1949); Malcolm Arnold, in his Concerto for Piano Duet and Strings (1951); William Bolcom, who explicitly called his Concerto for Piano and Large Orchestra (1976) a “reply” to Gershwin’s; and John Adams, in his Century Rolls (1996 – 99).

To call any of these pieces imitations of Gershwin would be ridiculous. These composers were reflecting their acceptance of the language Gershwin introduced to the concert hall, and registering the way in which that language became an available tool in the classical composer’s kit.

On the other hand, Arthur Benjamin and Constant Lambert, minor composers of Gershwin’s time, reflect the attitude that greeted Gershwin’s classical music initially, and still informs a lot of the reactions it generates from programmers and producers of classical music today. It’s a response colored (pun intended) by the confrontation of cultures in America that artists were only beginning to understand – cultural developments that were exciting to Gershwin but frightening to others. Critics and other composers alike looked down their noses at the ‘vulgar’ aspects of jazz (Benjamin called them “nauseating noises and . . . blatant rhythmic devices”) and sought to sanctify its “better” qualities (read: those qualities they understood and respected) within the holy confines of mainstream classical music. Though the attempts made by Benjamin and Lambert to improve Gershwin have charm and ingenuity, their works have fallen by the wayside now. Maybe the effort to make Gershwin’s work more substantial looked easy to them; Gershwin’s music is so tuneful, so straightforward, so seemingly simple. But those qualities can be deceptive, especially for people who have misgivings about the security of their own cultural values.

Composers who chose to engage Gershwin as a peer have produced work of much more lasting value than those who have underestimated him. However, it’s worth noting that most of the composers who used elements that Gershwin pioneered are still engaging with jazz indirectly, through his work. To call these pieces “jazz-influenced” is a bit of an exaggeration.

This raises an important core issue: how exactly did Gershwin understand jazz, and what aspects of jazz inform his classical compositions?

Howard Pollock’s George Gershwin: His Life and Work (University of California Press, 2007) provides a wealth of detail about the African-American musicians Gershwin knew and admired: W. C. Handy, Eubie Blake, Fats Waller, Willie “The Lion” Smith, James P. Johnson, Earl Hines, Duke Ellington, and Art Tatum are all specifically mentioned as people with whom Gershwin had some level of personal relationship. With the exception of Handy and Tatum, every one of these men was a pianist-composer, like Gershwin himself. It’s no wonder they found common ground.

William Bolcom: his 1976 concerto was a “reply” to Gershwin’s. Photo: Peter Smith.

Handy’s music is not exactly within the jazz tradition; he was and is thought of as a “blues” musician rather than a jazzman, although the borders between concert blues, jazz, and hot dance music were very blurry at the time. Tatum is also a special case; Gershwin was dazzled by his incredible facility at the piano, and by his inventiveness at interpreting Gershwin’s own songs.

Gershwin’s relationships with European-American jazz people seem to have been less personal than his contacts with African-Americans. From Pollock’s account, Gershwin was not a fan of New Orleans traditional jazz as played in the twenties; he heard the Original Dixieland Jazz Band live, but found their music “loud and much too discordant.” He reportedly admired Benny Goodman, and had some contact with Goodman, Jack Teagarden, and Gene Krupa, through their work in pit bands for his Broadway shows.

Gershwin imported a limited number of jazzy elements into his compositions for the concert hall. Syncopation, certainly. Extended instrumental effects, like growl trumpet, glissing clarinet and slurred trombone. Some use of saxophone and banjo. He allowed a bit of interpretive improvisation, but only when he was playing the piano. All of these are a part of jazz, but certainly not exclusive to it. Perhaps the most important “jazz” elements in Gershwin’s music are the hardest to quantify: forward drive and good-humored irreverence, which are as much representative of the spirit of the twenties as they are of jazz.

It might be more accurate to say that Gershwin’s music is informed by jazz rather than influenced by it. To some extent, if a composer chooses to follow Gershwin when he or she uses elements of popular music without introducing his or her own perceptions of it, the result will be informed by jazz in only a second-hand way. Fortunately, the more recent the composition under discussion, the more likely it is that the composer will have and use many more impressions of jazz than Gershwin did.

None of these caveats should be interpreted as criticism of Gershwin’s accomplishments as a composer, whatever genre you may put him in. He had the remarkable ability to create elegant and logical melodies, and the ingenuity to underpin them with harmonic shadings that add nuance and emotional depth. Anyone who listens to his music with both ears will immediately hear how beautiful it is, and, with a little more attention, they will also hear his admiration for the work of the African-American artists he knew and liked (along with the work of some European-American jazz artists). They will also hear in his greatest compositions a profundity that ranks them with the best art music.

American orchestras, for the most part, are still emphasizing Gershwin’s less serious works and usually relegating his music to Pops programs. In my survey of the 2014 – 2015 programs of 23 US symphony orchestras, programs of Gershwin songs and material from Porgy in Bess are inescapable, with RIB and American in Paris not trailing far behind. However, the Piano Concerto in F is notable by its absence. In my view, it ought to be programmed as often as Ravel’s Concerto in G; instead, the Ravel is receiving seven performances by American orchestras this season (in Boston, New York, Chicago, Houston, San Francisco, Atlanta, and Pittsburgh) while the Gershwin has only two (in Buffalo and Indianapolis, which are home to much less prestigious orchestras). American audiences will have two more chances to hear it, in Los Angeles in March and Seattle in April, thanks to a US tour by the London Symphony to celebrate the 70th birthday of Michael Tilson Thomas. But the fact that one English orchestra is giving Gershwin’s concerto as many performances as 23 US orchestras combined demonstrates that the priorities of American programmers are a bit askew.

Kirill Gerstein — a great contemporary interpreter, he is scheduled to play Gershwin’s Concerto at Tanglewood on July 3. Photo: Marco Borggreve.

To give appropriate credit to the home town team, the BSO is giving the Concerto the spotlight it deserves when the Tanglewood season opens on July 3. Kirill Gerstein, a great contemporary interpreter, will play it with the BSO for the first time that night. The program is a laudably serious all-American affair. Jessye Norman will narrate Copland’s Lincoln Portrait. Duke Ellington’s Harlem is also on the bill.

There is nothing inherent in Gershwin’s concerto that can account for its neglect by other American orchestras. It seems incredible that programming such a tuneful piece should represent a risk for any orchestra’s management.

Ethel Merman’s remarks above are typical of the reactions Gershwin’s friends and acquaintances had to him. They recognized a magic in his immediate presence, but they also knew intuitively that he was going to transcend his time. He had a little more than 20 years as a professional composer and pianist. He died in 1938 at 37, two years older than Bob Marley was at the time of his death. He lived eleven years beyond Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, Kurt Cobain, and Amy Winehouse. His life, like each of theirs, is an unfinished story, but his music and its influence show no signs of mortality. And yet, there are still some places where he is underappreciated, and regrettably, they include most of the concert halls in his home country.

These piano concertos, listed chronologically, show the specific influence of Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue and Concerto in F:

Arthur Benjamin (1893 – 1960): Concertino for Piano and Orchestra (1927)

Maurice Ravel (1875 – 1937): Concerto in G (1929 – 1931)

[Nadine] Dana Suesse (1909 – 1987) [orchestrated with Ferde Grofé]:

Concerto in Three Rhythms [for Piano and Orchestra] (1932)

Hisato Ohzawa (1907 – 1953): Piano Concerto No. 2 (1935)

Thomas Pitfield (1903 – 1999): Piano Concerto No. 1 in e minor (1946-47)

Francis Poulenc (1899 – 1963): Concerto for Piano and Orchestra (1949)

William Bolcom (1938 – ): Concerto for Piano and Large Orchestra (1976)

Nikolai Kapustin (1937 – ): Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 4, Op. 56 (1989)

William Thomas McKinley (1938 – ): Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 3 (1994)

Michel Camilo (1954 – ): Concerto [No. 1] for Piano and Orchestra (1997?)

These non-concerto works for piano and orchestra, listed chronologically, show the specific influence of Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” and Concerto in F:

James P. Johnson (1894 – 1955): Yamekraw, A Negro Rhapsody

(orchestrated by William Grant Still) (1927 – 28)

Jean Françaix (1912 – 1997): Concertino (1932)

Richard Rodney Bennett (1936 – 2012): Party Piece, “For Young Players”

[for Piano and Chamber Orchestra] (1971)

These piano concertos, listed chronologically, are influenced by Gershwin’s work as a whole:

Aaron Copland (1900 – 1990): Concerto for Piano and Orchestra (1926)

Bela Bartók (1881 – 1945): Concerto for Piano [and Orchestra] No. 2 (1930 – 1931)

(Leonard) Constant Lambert (1905 – 1951):

Concerto for Piano and Nine Instruments (1931)

Francis Poulenc (1899 – 1963): Concerto in d minor for Two Pianos and Orchestra (1932)

James P. Johnson (1894 – 1955): Concerto Jazz-a-mine aka Piano Concerto in A-flat (1934)

[two movements only; the final movement is lost]

Leo [Leopold] Smit (1900 – 1943): Concerto for Piano and Wind Orchestra (1937)

Benjamin Britten (19193 -1976): Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, Op. 13

(1938 version, with “Recitative and Aria” as third movement)

William Schuman (1910 – 1992): Concerto for Piano and [Small] Orchestra

(1938, rev. 1942)

Juriaan Andriessen (1925-1996): Concerto for Piano and Orchestra (1947- 48)

Gian Carlo Menotti (1911 – 2007): Concerto in F for Piano and Orchestra (1948)

Malcolm Arnold (1921 – 2006): Concerto for Piano Duet and Strings, Op. 32 (1951)

Ned Rorem (1923 – ): Piano Concerto No. 2 (1951)

David Broekman (1899 – 1958): Concerto for Piano, Percussion and Orchestra

(“A Parisian in New York: To the Memory of George Gershwin”) (1955)

Malcolm Williamson (1931 – 2003): Piano Concerto No. 2 in f-sharp minor (1960)

Malcolm Williamson (1931 – 2003): Piano Concerto No. 3 in E-flat (1962)

Malcolm Williamson (1931 – 2003): Concerto [in a minor] for Two Pianos

and String Orchestra (1971)

Tobias Picker (1954 – ): Keys to the City [for Piano and Orchestra]

(also known as Piano Concerto No. 2, “Keys to the City”) (1983)

Peter Lieberson (1946 – 2011): Piano Concerto (1983? -1984)

John Adams (1947 – ): Century Rolls [for Piano and Orchestra] (1996? – 1999)

Roel van Oosten (1958 – ): Piano Concerto (2001)

Brent Edstrom (1964 – ): Concerto No. 1 for Jazz Piano and Orchestra (2007)

These non-concerto works for piano and orchestra, listed chronologically, are influenced by Gershwin’s work as a whole:

George Antheil (1900 – 1959): A Jazz Symphony for Piano and Orchestra (1925 – 1927)

[revised by Antheil in 1955]

Morton Gould (1913 – 1995): Interplay aka American Concertette No. 1

[for Piano and Orchestra] (1943)

Paul Schoenfield (1947 – ): Four Parables for Piano and Orchestra (1982 – 83)

To help you explore the compositions mentioned above as easily as possible, my full chronology of JIPCs contains detailed information on recordings of these works, including CDs, Spotify access, and YouTube links. In addition to Gershwin’s Concerto in F and Rhapsody in Blue, the chronology also contains information on two other Gershwin works for piano and orchestra, the Second Rhapsody (1931) and the I Got Rhythm Variations (1933 – 34).

Next in the Jazz and Piano Concerto Series — French Thread

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.

He is the co-author of Burning Up the Air (Commonwealth Editions, 2008), which chronicles the first fifty years of talk radio through the life of talk-show pioneer Jerry Williams. He is a former member of the board of directors of the Massachusetts Broadcasters Hall of Fame.

Tagged: George Gershwin, Jazz-Influenced Piano Concertos, Piano Concerto in F

I agree with everything here, but I kind of hate to hear the Gershwin songs referred to as “lesser” works. As others such as John Lennon have pointed out, a song can be a work of art as powerful and eternal as any other art form. Gershwin’s songs sustain, encourage, and console his listeners.