Poetry Review: “It’s Like That If You’re Alive” — The Poetry of Tone Škrjanec

Looking deeply into things and, by no means least of all, into other human beings implies meditating on brevity, on ephemerality—and this is what Tone Škrjanec does in this book.

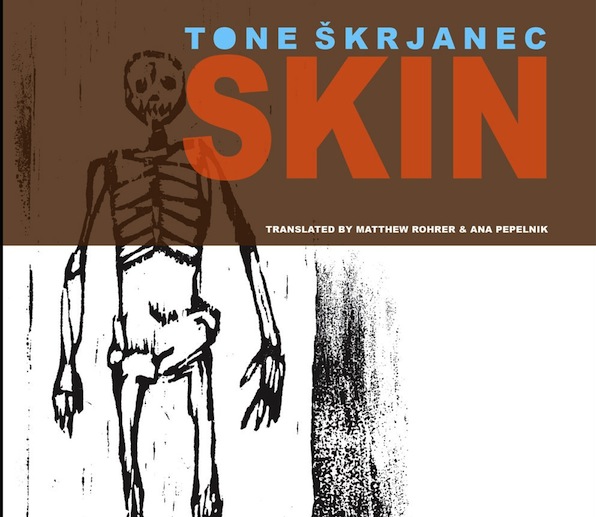

Skin by Tone Škrjanec, translated from the Slovene by Ana Pepelnik and Matthew Rohrer, Portland, Oregon: Tavern Books, 88 pp., $17.

By John Taylor

If Tone Škrjanec’s reputation as a Slovene “beat poet” had not reached my ears, I would not have thought of this American movement from the 1950s and 1960s while I was reading Skin, the new translation (by Ana Pepelnik and Matthew Rohrer) of his book Koža (2006). Well, this is perhaps not entirely exact. Škrjanec (b. 1953) has indeed translated works by William S. Burroughs, Charles Bukowski, Gary Snyder, Kenneth Rexroth, and others (like Paul Blackburn and Anselm Hollo) more or less associated with the American Beats. Yet labeling him a “Beat” is like placing an opaque filter between our eyes and his words. Undeniably, some Zen-hippie-like light sifts through; of the poets and writers whom he has translated, the respective oeuvres of Snyder and Rexroth suggest some analogies with lines celebrating, for example, “the blackbird’s yellow beak / carelessly jumping around in the rain, / a blunt can opener, all the beauties of animate and inanimate nature / demanding our immense and absurd attention,” as he puts it in the poem “Rahat Lokum.” But even as Snyder and Rexroth have distinct literary sensibilities, so does Škrjanec. It would misleading to contrive additional parallels. The résumé on the back cover of the American collection is right on target because it ignores the putative Beat connection and emphasizes the Slovene poet’s philosophical import, notably his attentiveness to the enigmas of consciousness:

His poems exist between the world of things and the mysteries of consciousness in language that is direct, shape-shifting, and lyrical. The underlying poetic procedure is assembly. His aim is to magnify and celebrate. [. . .] Škrjanec’s is the poetry of a mindful observer.

His mindful observing draws out not only the mysteries of consciousness but also the irony, the touching aspects, indeed the obliquely uplifting elements in what he sees. “I love little events,” he writes in an erotic poem first set in Prague and then recalling “a morning in Greece with a long walk on the slope / to the first coffee and goat yogurt.” Time and again the poet focuses on a seemingly trivial object or a minor happenstance, juxtaposing it with some other oddity of matter or movement. This is what the above blurb means by “assembly.” Škrjanec pairs disparate entities. Sometimes a concrete thing and a more abstract notion are joined in a thought provoking relationship. In “History,” for instance, “the cut piece of salami / persistently drying on a plate is also / part of history, as is the fly buzzing over it.” The opening lines of another poem, “Creatures,” seemingly reply to the preceding image:

it’s like that if you’re alive.

little things everywhere.

the zoo and the racetrack.

breathing. flies

that crash

into the lit bulb.

Note that first line: “it’s like that if you’re alive.” I don’t have the Slovene original with me, but, in English at least, the “if” is arresting here. You who are reading this article as well as I who am writing it—we are at least alive in the most rudimentary, biological, sense of the term; but the “if” in Škrjanec’s poem hints that we may acquire a higher or richer aliveness or, to put it differently, an intensified awareness. In other words, “if” our awareness is heightened (and reading Škrjanec’s verse heightens it), then we might well perceive that “every stone has its own story,” as he states in “Too Much Void,” and that “every shadow a few good ideas about moving.” The poet gets us to look not only more closely at stones and shadows, but also more deeply into them.

Looking deeply into things and, by no means least of all, into other human beings implies meditating on brevity, on ephemerality—and this is what Škrjanec does in this book. Essentially, he makes this query: if “everything’s temporary,” as he states in “Noises are in the Air,” can any depth or permanence whatsoever be found anywhere in our existences? And if every experience, every perception, is superficial and fleeting, what is the point of our aliveness?

Poet Tone Škrjanec — if he ruminates, he spares us the details.

Yet if such questioning and self-questioning underlie his poems, he is by no means solemn, overbearing, lugubrious, or even overtly “poetic” in his manner of carrying out these tasks. In fact, the questioning and self-questioning are left unstated in the margins, between the lines, or in the pre-text motivating or silently accompanying his poem. If he ruminates, he spares us the details. What he offers us, however, are flashes of something rather more lasting than fugacity. (We can’t hope for permanence on this earth.) Call it “presence,” for lack of a better term, as do some (otherwise varied) French poets (Yves Bonnefoy, Philippe Jaccottet, Pierre-Albert Jourdan, Jacques Réda et al.) from the same generation as that of the American Beats. I have no idea whether Škrjanec has read these and other like-minded French poets, not to forget the Surrealists (who also yoked heterogeneous entities together), but their philosophically informed poetics, and his, make me inclined to usher them into the same room, for a while, while the American Beat poets wait patiently outside in the hallway.

In other words, now and then something strikes Škrjanec and remains present to his consciousness a little longer and more compellingly than usual. The epiphanic occurrence perhaps even gives him an inkling of transcendence, though this feeling might well be illusory, as he knows, and is thus (almost) entirely dismissed as wishful thinking; whence, I suspect, his tendency to underscore the amusing or absurdist nature of certain unexpected and even miraculous configurations like “the wet eye of a deer / a thick layer of velvet in the sky.” Why does one specific thing or event or sensation, or one particular juxtaposition of two phenomena, provoke this impression of “presence,” and not another? This is the mystery at the heart of Skin, even as it is the mystery at the heart of our aliveness. At times (rarely), something very special happens. In “Noises are in the Air,” Škrjanec notes that some faces can cast the spell. Here is the whole poem:

everything’s temporary

in the shade of some unknown tree

standing by the shade of a flowering oleander

with pale pink blossoms.

some flowers, yellow and red,

open only in the evening

when actual shadows appear,

when the sun isn’t so strong anymore,

when people and stories gradually

begin to disappear in the dusk, yet,

how some faces

appear just once

and never disappear.

Epiphanies of presence do not always occupy the forefront of Škrjanec’s verse. Other pieces point the way home, as it were, as he works himself from an initial impression of “hollow dilemmas, / nervous hesitations. the day gray / and kind of impersonal. like it’s not even there” toward a fuller, more tangible engagement with reality. The poem “Gray Light,” from which these lines are quoted, is exemplary in this respect. The lack, absence or “not-thereness” sensed at the onset by the poet is soon dispelled by “circular saws [. . .] singing outside,” by a dog jumping up and down, by a woman passing by the window and giggling, and, finally, by “breasts touch[ing] the strings, / making them bend and / release an unclear, quiet sound.”

The preceding lines as well as the title of the collection indicate that Škrjanec’s verse often has an erotic dimension. Tactile sensation forms a leitmotiv in Skin, ranging from the poet’s naked “skin relatively soft / on the rough textile / of the aged armchair” to subtle erotic synesthesia involving “music that touches the tip / of genitalia / very lightly with a tongue.” There is much stylistic finesse and perceptive delicacy in such writing. So often in this book, sense impressions, which represent ephemerality par excellence, take on a luminous, relatively lasting, and haunting quality as Škrjanec deftly recovers some of the discreet and alluring plenitude of reality.

[This review first appeared in Slovene, in a translation by Leonora Flis, in the print journal Literatura, Vol. 17, Nos. 283-284, January-February 2015; and note the excellent Slovene literary website that is associated with the journal.]

John Taylor writes about several other Slovene poets in his two collections of essays, Into the Heart of European Poetry (Transaction, 2008) and A Little Tour through European Poetry (Transaction, 2014). His most recent personal book is If Night is Falling (Bitter Oleander Press, 2012), which was indeed prefaced by the Slovene poet Veno Taufer. His translation of Philippe Jaccottet’s The Pilgrim’s Bowl (Giorgio Morandi) has just appeared at Seagull Books. He lives in France.

Tagged: Poetry, Skin, Slovene, Tavern Books, Tone Škrjanec