Music Commentary Series: Jazz and the Piano Concerto — Who Will Buy?

This post is part of a multi-part Arts Fuse series examining the traditions and realities of classical piano concertos influenced by jazz. The articles are bookended by Boston Symphony Orchestra concerts: the first features one of the first classical pieces directly influenced by jazz, Darius Milhaud’s Creation of the World (February 19 – 21); the second has pianist Jean-Yves Thibaudet performing one of the core works in this repertoire, Maurice Ravel’s Concerto in G (April 23 – 28). Steve Elman’s chronology of jazz-influenced piano concertos (JIPCs) can be found here. His essays on this topic are posted on his author page. Elman welcomes your comments and suggestions at steveelman@artsfuse.org.

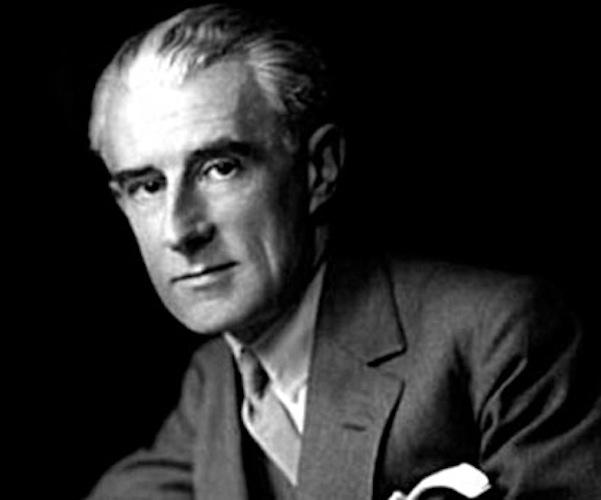

Composer Maurice Ravel — he penned one of the few popular jazz-influenced piano concertos.

By Steve Elman

The question comes from Cole Porter’s arch and jaundiced “Love for Sale,” a “slightly soiled” abstract of harlotry:

Who will buy?

Who would like to sample my supply?

Who’s prepared to pay the price

For a trip to paradise?

Whether Porter intended it or not, this stanza perfectly expresses one necessary aspect of the creative endeavor. It’s only in the mind of the naïve consumer that a musician or visual artist exists in an ivory tower, unsullied by commerce. Unless the artist has a completely independent source of income (Charles Ives’s insurance business, or a MacArthur “genius” grant, for example), he or she has making a living in mind, even when creating the most esoteric work. Composers want their music played in a concert hall, or at the very least commissioned. Visual artists want their work seen in a gallery or museum, or at the very least purchased for private display. If one deliberately creates something with “no commercial potential,” as Frank Zappa once put it, one must do so in full awareness of that fact (but with a sneaking hope that it will find customers anyway).

That’s right – customers. Without one or more people willing to pay for it, art is masturbation. Conversely, with one or more people willing to pay, art is a kind of prostitution.

Here be dragons.

In considering any artistic genre, any tradition of creative work, this question is as inevitable as death and taxes: what is the nature of the person willing to pay for art? More specifically to the topic of this series, what kind of person would be willing to lay out his or her hard-earned cash for a CD or a live performance of a jazz-influenced piano concerto?

This potential buyer of a JIPC is no different from any consumer. He or she must want to own, or at least be willing to pay to hear, the music. At minimum, he or she has to be driven by curiosity. More likely, he or she probably wants to have an experience similar to others that have been pleasurable and satisfying. Depending on how many pleasurable and satisfying musical experiences the person has had, and how deeply the person may have explored his or her own capacity for appreciation, this desire could range from near-indifference to absolute passion. The closer it gets to passion, the more likely it is that the person would buy.

But another factor trumps all of these. A study of data through 2012, sponsored by the National Endowment for the Arts and released in January this year, points strongly to something that may seem obvious but must be emphasized: people prefer enjoying art with friends and / or family. In fact, the study concludes that “socializing with friends or family members was the most common motivation for arts attendance.” Collective experience, along with the pleasure that comes from dinner or drinks before or after, enriches artistic experience. So one person’s passion can drive others (maybe others who are not initially interested) to a concert or a play or an exhibition.

(A side note: this will not be news to the organizers of Groupmuse, the series of home-based chamber music concerts that is attracting hundreds of new listeners with precisely this purpose. As their website says, “Art is better with your friends.” An Arts Fuse interview Sam Bodkin, founder and CEO of Groupmuse.)

One thing is certain: the people willing to pay represent a small subset of the people willing to hear. One of the rules of thumb I learned from my many decades in public radio, where some listeners pay directly for something they can get for free, is that only a small slice of the interested population (usually about ten percent) cares enough about ANYTHING to pay for it, even when they are subject to begging and pleading.

This percentage can be driven up by peer pressure or simply by an awareness that the product, whatever it is, has been purchased by a lot of other people. We poor simians are still deeply driven to reach out for something that other simians seem to like, sometimes to our regret; a large number of the people who bought Michael Jackson’s Thriller LP quickly tired of it and never want to hear it again.

On the other hand, the percentage can be driven down by how much difficulty we have in finding the product and how many other ways we can find to spend our money.

Hold on, says the armchair analyst (I was one a long time ago, and can speak authoritatively). Wouldn’t JIPCs appeal to people who like piano concertos AND people who like jazz? Doesn’t that open up a potentially bigger audience than there would be for either separately?

The answer is: No.

It appears to be true of all hybrid or cross-genre forms that only those people who are attracted by both or all of the forms that contribute to the hybrid will be interested in it. In other words, you have to like jazz AND like classical piano concertos to be interested seriously in the JIPC. There is something of a sliding scale to this, but only at the extremes – the jazz fan interested in everything jazzish might take a flyer on a jazz-influenced classical work every now and again, just as the devoted classical aficionado might dip into a JIPC to hear something fresh.

Perhaps most of these observations seem self-evident. In any event, they offer a grim prospect for the JIPC.

Of the 50 or so existing JIPCs, only two have any measure of popularity – Ravel’s and Gershwin’s. What are the chances that a listener with an idle interest in either would be exposed to other JIPCs? Do the resources of on-line streaming offer opportunities for the curious to discover more of them?

As an experiment, I entered “Gershwin” into my Pandora account and selected the “George Gershwin – Composer” option. The first work Pandora’s algorithms chose? “Rhapsody in Blue,” of course, which I tagged with a thumbs-up. The version in Pandora’s library is not one of the many well-known recordings, but it is very well-played (by pianist Michael Boriskin, with the Eos Orchestra, led by Jonathan Sheffer).

Next came the first Gymnopédie by Erik Satie, in a sensitive rendition by Pascal Rogé. Then “Hoe-Down” (the “beef-it’s-what’s-for-dinner” theme) from “Rodeo” by Aaron Copland. Then back to the Boriskin – Sheffer CD for a really fine performance (which I hadn’t heard before) of Gershwin’s Second Rhapsody. Another thumbs-up.

And then the algorithms began to lead me far afield. A number from Tchaikovsky’s “Swan Lake.” Benny Goodman’s recording of “Sing Sing Sing.” (How did this get in? It’s not even Goodman playing Gershwin.) Then “Jupiter” from Holst’s Planets. The overture from Verdi’s La Traviata. No concerto. No piano.

Just when I was about to give up, the algorithms went back to Boriskin and Sheffer for the first movement of Gershwin’s Piano Concerto in F. This may be the only recording of Gershwin orchestral music to which Pandora holds the rights, but it’s worthwhile, and I gave it a thumbs-up anyway.

And then? Uh-oh. The first of Satie’s Gymnopédies again, this time in Debussy’s orchestral version. Followed by one of Chopin’s nocturnes played gorgeously by Arthur Rubinstein (great music, but nowhere near the center of my search). When the algorithms went on to one of Brahms’s Hungarian Dances, I knew we’d never get to Ravel.

Pandora itself is not really at fault – its algorithms work much better for popular music than for classical, and they reflect the preferences of average listeners. The classical menu it generated – cued by the word “Gershwin” — made for very good listening, as far as it went. The system has not been designed to take anyone into unfamiliar musical territory.

And this is the hardest truth of all when we consider the question of who will buy: the average listener, and even one with a good deal of sophistication, views unfamiliar music with considerable skepticism. Anything unfamiliar that moves beyond the basics of appeal – singable melody, danceable rhythm, spiritual uplift – is often perceived as uninteresting, sometimes as frightening and, in rare cases, infuriating. The story of the riots at the premiere of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring has been told so often that it has become a cliché, but what is often forgotten is how different the reception for it became once audiences knew what to expect from it – a process that took only a year or so.

In short, it is almost impossible to drag a typical listener into unfamiliar musical territory, even with a firm promise of “Try it, you’ll like it.” (The NEA study suggests that a social evening including unfamiliar music would have a better chance of success here, but that would require at least one person taking the lead and hyping a concert to others.) Encouraging the typical listener to buy unfamiliar music thus becomes a considerable challenge.

There are a number of atypical listeners – people like me, I guess – who have learned not to be afraid of the unfamiliar. Somehow, we came to enjoy the sparks set off in the brain by new sounds – sometimes downright strange sounds. Those sparks tickle us and delight us now, and we can’t imagine life without this particular pleasure.

What’s worse is that few of us remember what it was like before we trained our minds to explore the unfamiliar, and we can’t imagine why other people don’t share our delight in it. I’ve done a good deal of thinking about this, and a case history may be instructive: the first time I heard Thelonious Monk.

I was in the habit, all those years ago, of going to the library and checking out LPs (remember LPs?) almost at random. I had been exposed to a wide range of music in my father’s record collection and the collections of other adults – I remember bluegrass guitarist Arthur Smith and his Fingers on Fire, a record by the pre-bossa nova Brazilian band led by Mario Gennaro Filho, accordion tunes by Jo Basile, Command Records’ series of audiophile recordings, Herb Alpert and the Tijuana Brass, Percy Faith, Ray Conniff, Bent Fabric’s “Alley Cat,” society dance medleys by Lester Lanin and his orchestra, and especially the records of Art Tatum, my father’s demigod.

One of the LPs I took from the library was an interesting-looking classical number called “Pictures at an Exhibition,” by some Russian composer. I checked out a Dave Brubeck record because he’d been on the cover of Time. I listened to an anthology from the Playboy Jazz Festival because . . . well, you know why . . . which was where I heard Gerry Mulligan play a tune with the great title of “Utter Chaos.”

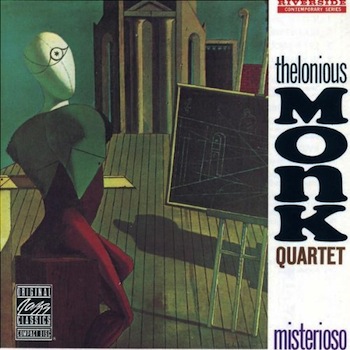

And I checked out Monk’s “Misterioso,” with its riveting surrealist cover art by Giorgio de Chirico that probably hooked me before anything else, and reverent notes by some guy named Gunther Schuller who was supposed to be a big deal musically. At the time, Monk was talked about in the mainstream press as “the high priest of bebop,” an odd, even dangerous kind of musician, a guy who deliberately hit adjacent piano keys to get the sounds “between the notes.” I had never heard anything like those tunes, “Nutty,” and “Blues Five Spot,” and the title track, filled with surprising stops and starts, unpredictable melodies that somehow resolved themselves at the last second, and a piano sound that was the antithesis of fluid. Johnny Griffin’s tenor playing was hard and tough, a world away from Paul Desmond’s alto. It was all so WEIRD, but it was irresistible. In those hours listening and re-listening to Monk, trying to make sense of Schuller’s comments, I knew that I’d found something very special, even though I didn’t really understand it – it was like I’d been inducted into a secret society.

Looking back on the experience, I can identify the extra-musical things that intrigued me – the cover art, the brief moment I’d seen Monk on TV in the film Jazz on a Summer’s Day, the whole atmosphere of coolness and hipness that floated around him, his rep as an outsider.

Intrigue. No one had led me to Monk and I probably would have resented the attempt if someone had tried. Temptation. You could even call it marketing.

Violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter — we need more and cleverer marketing of serious music.

Yo-Yo Ma’s genial grin is a kind of marketing. Calling his world music adventure The Silk Road Project, with its atmosphere of exotica – that’s marketing, too. Anne-Sophie Mutter’s slinky gowns. Gustavo Dudamel’s hair. That austere, mystical look on Mitsuko Uchida’s face. Andris Nelsons’ aw-shucks style. Martha Argerich’s stubborn resistance to studio recording. John Adams’s decision to write an opera in which Richard Nixon, Mao Zedong, Henry Kissinger, and Chou En-Lai are characters. The Composers in Red Sneakers giving free admission to anyone sporting the proper footwear. Everything about the Kronos Quartet. Intrigue. Temptation. Marketing.

But there’s not enough of it, and it’s not clever enough by half to rescue the classical music business. Giant orchestras with burdensome budgets and vast endowments. Concert experiences that are leaden with tradition and hamstrung by the trappings of class. Academic institutions that deaden the creativity of young musicians by pointing to career paths of duplication and imitation.

The writing is on the wall, and it’s not just a warning to the composer who trifles with the idea of writing a JIPC. It’s a warning to everyone who takes music seriously.

In a world of music as product, people who love the spark of the new have to share that love unashamedly. They have to open their arms to those frightened by new things or watch what they love wither away to nothingness. They have to create social occasions so that others can comfortably appreciate how much damn fun good music can be. Charisma, glamour, wit, and star power ought not to be déclassé. Melody and good cheer ought not to be relegated to Pops programs. Above all, the classical music world has to abandon the notion that mere excellence and adherence to tradition will eventually draw an audience.

All around us, the marketers are singing a song of disposability. Download what appeals to you now, and delete it when it bores you, as it inevitably will. What’s coming out tomorrow will surely be more important than what you listened to yesterday. Everyone makes music; who needs virtuosi?

Who will buy? Who’s prepared to pay the price for a trip to paradise? And perhaps even more important: who knows the paradise that live performance can be?

Enticing interest in serious music must begin and end with the experience of live performance. If the skeptics can be brought into the concert hall, where they can hear and see music in three dimensions, where instrumental mastery is enriched by soul-stirring understanding, and where a bond can be established with listeners who love music and show it, the doubters will want more. And they may be more willing to give the people who love music the chance to intrigue them further.

They may even give a jazz-influenced piano concerto a listen. If they get the chance to hear one.

Composer George Gershwin — Melody and good cheer ought not to be relegated to Pops programs.

More:

In the spirit of exposing these compositions to as many people as possible, I have provided information below about their on-line availability. YouTube links were operative as of this writing; however, the reader should note that these postings appear and disappear without warning. Spotify provides a more reliable resource, and also provides at least minimal compensation to the copyright holders.

George Gershwin (1898 – 1937): Concerto in F for Piano and Orchestra (1925)

Recommended recordings:

Marc-André Hamelin, p; Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra; Leonard Slatkin, cond [Rec. 2006, Amsterdam Concertgebouw] Available via YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DxUHcXUJZgY

Garrick Ohlsson, p; San Francisco Symphony Orchestra; Michael Tilson Thomas, cond [Rec. 2004; issued on RCA CD]. Available via Spotify

Oscar Levant, p; New York Philharmonic Orchestra; André Kostelanetz, cond [Rec. 1949; originally issued in 78 rpm set; reissued in “Levant Plays Gershwin,” CBS CD, 1987] (Time: 30:55) Not available on line.

Maurice Ravel (1875 – 1937): Concerto in G [for Piano and Orchestra] (1929 – 1931)

Recommended recordings:

Jean-Yves Thibaudet, p; Orchestre symphonique de Montréal; Charles Dutoit, cond [Rec. 1995, Montréal; issued on London CD, 1996] Available via Spotify.

Pascal Rogé, p; Vienna Radio Symphony, Bertrand de Billy, cond [Rec. 2004, Vienna; issued on Oehms CD, 2005] Available via Spotify.

Pierre-Laurent Aimard, p; Cleveland Orchestra, Pierre Boulez, cond [Rec. 2010, Cleveland; issued on Deutsche Grammophon CD, 2010] Available via Spotify.

Leonard Bernstein, p & cond; “Columbia Symphony Orchestra,” a studio ensemble of New York-based musicians selected by Bernstein [Rec. 4/7/58, New York City; originally issued on Columbia LP, 1958; reissued on Sony Classical CD, 1992] (Time: 21:33) Not available on line.

To help you explore other compositions mentioned in the piece above as easily as possible, my full chronology of JIPCs contains detailed information on recordings of these works, including CDs, Spotify access and YouTube links.

Next in the Jazz and Piano Concerto Series — Who Will Program?

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.

He is the co-author of Burning Up the Air (Commonwealth Editions, 2008), which chronicles the first fifty years of talk radio through the life of talk-show pioneer Jerry Williams. He is a former member of the board of directors of the Massachusetts Broadcasters Hall of Fame.

Tagged: jazz piano concerto, Piano Concerto