Theater Review: “Sontag: Reborn” — A Song of Herself

Dramatically speaking, Sontag: Reborn fails to treat a flawed iconoclast with the necessary creative playfulness. Hush, Saint Susan Aborning!

Sontag:Reborn, based on the books Reborn: Journals & Notebooks 1947 – 1963 and Consciousness is Harnessed to Flesh. Adapted and performed by Moe Angelos. Directed by Marianne Weems. Presented by The Builders Association, the New York Theatre Workshop and Arts Emerson at the Paramount Theatre, through May 18.

By Bill Marx

First, my Susan Sontag story, condensed: when I was working as an arts contributor at WBUR I interviewed Sontag in the early ‘80s. I don’t remember the exact date, and I am still rummaging around for the tape. I met her at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and she must have been strolling about the gallery, because I recall trying to keep the old heavy tape machine from crashing against my side because it would knock me into the art work. I made sure to keep up with her, holding a shaky microphone (I was nervous) close to her mouth.

Sontag was distant but polite, as if this questioning was something she had to put up with. I had read much of her critical work before, but she was in town because of a screening at the MFA, so the conversation mainly revolved around films. My strongest memory is that I asked her what was her favorite recent American film. She immediately responded that it was 1979’s Star Trek: The Motion Picture and that it was a masterpiece. I had seen the film and thought it was a bloated bore. I probably blanched in disbelief because she cocked an eyebrow and launched into a paean to the movie’s marvelous visuals and powerful exploration of peace between man and technology. Evidence that Sontag was a Trekkie? Or was she pulling my leg, indulging in a bit of Camp fakery? Who knows?

If only there was more of that kind of off-speed theatrical perspective in The Builders Association’s occasionally compelling but generally flat one-woman show Sontag:Reborn, which is mostly based on material drawn from the eponymous first volume of Sontag’s journals, with some passages from a later volume, Consciousness is Harnessed to Flesh. Both books were edited by her son, David Rieff, who in his introduction to Reborn warns readers not to expect any self-deprecating humor: “This is a journal where art is seen as a matter of life and death, where irony is assumed to be a vice, not a virtue, and where seriousness is the greatest good.” Adaptor and performer Moe Angelos and director Marianne Weems never question Sontag’s ultra-earnest tone (Rieff seems to be a bit embarrassed by it) and, dramatically speaking, that means that they fail to treat a flawed iconoclast with the necessary creative playfulness. Hush, Saint Susan Aborning!

Accordingly, Sontag:Reborn moves along with the pizazz of an instructional film, with Angelos skillfully portraying Sontag as she matures into glory, with factoids about her impressive educational achievements announced along the way. The performer delivers snippets of the writer’s brusque prose, which includes long reading lists, bits and pieces of ideas, reflections on self-fashioning, an amusing teenage visit with Thomas Mann, and the discovery of lesbian appetites (including observations on an affair with dramatist María Irene Fornés). Sontag sees her sexuality as the key to her growth as a writer and thinker, but she remains irritatingly reluctant to gaze beyond the ascetic walls of her open-and-shut consciousness. There are only a few glimpses into the wide world of the ’50s and ’60s. The assassination of President John F. Kennedy is alluded to — but the Civil Rights Movement is not mentioned.

From the age of 16, Sontag reveals herself to be a non-stop judger, of herself and others, obsessed with coming up with the right severe verdicts. She is continually wobbling between handing victory over to the abstract fruits of highbrow culture or to the Dionysian gusto of the body. Sometimes she desires to be alone, cruel, and self-sufficient — then suddenly she needs companionship and a domestic life. She inexplicably marries mentor Philip Reiff and, after giving birth to a child, David, leaves her family to construct the radical underpinnings for the “Against Interpretation” Sontag that would push the New York Intellectuals off their perch. Along the way she celebrates, cuddles, lashes, pokes, prods, and pulverizes her ego for the sake for some sort of grand entrance into a cerebral valhalla without ever calibrating the price she (or others) may have to pay for her to get there.

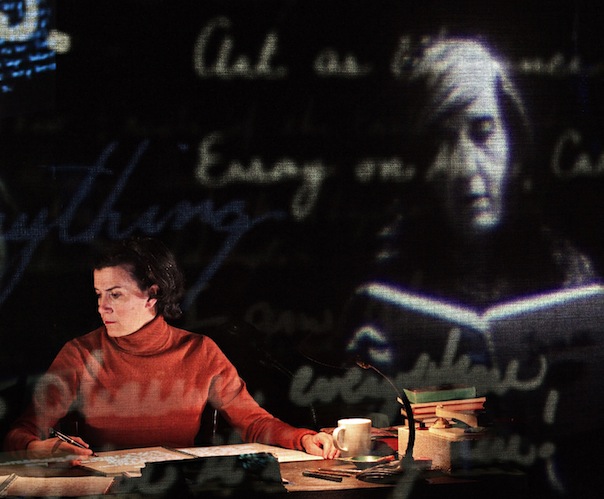

Because Angelos and Weems are determined to celebrate rather than examine Sontag’s journey to greatness, they miss powerful opportunities to step outside of the strict lines provided by the journals. The Builders Association uses video projections beautifully — a striking visual palimpsest is created: photos, book titles, and bits of Sontag’s handwriting drift over one another in space. But the effect is largely decorative — Sontag mentions seeing a film starring Marlene Dietrich and you get a picture of the star. It is as if you are at a fancy slide show. A bigger miscue is a large video production of the head of an older Sontag (Angelos), which hovers by the side of the writer’s younger self. Instead of using the mature Sontag to comment on, laugh at, or challenge her rookie persona, the image puffs on a cigarette, raises its eyebrows from time to time, and supplies background info or explicates literary references. The latter help to set up the Warner Brothers-bio inspired ending, when the titles of Sontag’s books and essays fly up into the heavens, presumably to land on God’s library shelves.

Of course, the problem is that Sontag became a bit of an intellectual/moral scold in her later years, at least as a critic. The early Sontag, who broke down stale divisions between high and low culture, is long gone. The former could write that “Camp taste is a kind of love, love for human nature. It relishes rather than judges, the little triumphs and awkward intensities of ‘character’ … Camp is a tender feeling.” (There is not much tenderness in the journals. It took a fierce woman to write on the pleasures of Camp.) The older Sontag had hardened up considerably — she was the armored warrior guarding the elitist gates against the barbarians. She would most likely have had little patience with the dithering seedling of the journals, who had more than a touch of the barbarian about her. As Phillip Lopate argues in his superb Notes on Sontag, “She was an enthusiast — a lover, not a skeptic — who needed to fall hard for a position and convince herself it was the only one.” The Builders Association follows in Sontag’s one-sided footsteps — it has no doubts about the show’s heroine, no matter how creepy and self-serving she may be. The result is that Sontag: Reborn gives us hagiography rather than the kind of theater Sontag preferred — plays that make us think.

Bill Marx is the Editor-in-Chief of The Arts Fuse. For over three decades, he has written about arts and culture for print, broadcast, and online. He has regularly reviewed theater for National Public Radio Station WBUR and The Boston Globe. He created and edited WBUR Online Arts, a cultural webzine that in 2004 won an Online Journalism Award for Specialty Journalism. In 2007 he created The Arts Fuse, an online magazine dedicated to covering arts and culture in Boston and throughout New England.

Tagged: ArtsEmerson, Marianne Weems, Moe Angelos, Sontag:Reborn, Susan-Sontag