Fuse Commentary: Book Review Blues

Bloggers are concerned about the fate of book reviews, so raising questions about the quality of book commentary online, especially asking how it can become better, is worth the effort. But any discussion about the future of reviews must be based in reality rather in wishful thinking or defensive delusion.

By Bill Marx

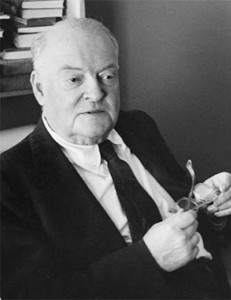

Critic Edmund Wilson — he wondered if substantial critics could exist in 1928. If he were alive today he would still be wondering if serious criticism has a chance.

In an article in the Boston Globe, literary critic Sven Birkerts jumps to the barricades in the current battle between book reviewers loyal to print and those who feel that the future of book culture will be on the blogosphere. Alarmed that book review supplements are shrinking (or in some cases disappearing) in the country’s major newspapers, Birkerts fears that the most valuable aspects of traditional book criticism will be lost in the ever-expanding echo chamber of the Internet. The National Book Critics Circle agrees: the organization has mounted a noisy campaign to save book reviewing in the name of preserving the country’s intellectual life.

Bloggers are as concerned about the fate of book reviews as Birkerts, so raising questions about the quality of book commentary online, especially asking how it can become better, is worth the effort. But any discussion about the future of reviews must be based in reality rather in wishful thinking or defensive delusion.

What is that reality? Those tempted to accept the high evaluation of professional book critics by the reviewers themselves should turn to Edmund Wilson, who, in his 1928 essay “The Critic Who Does Not Exist,” set down the truth for now as well as then: “When one considers the number of reviews, the immense amount of literary journalism that is now being published in New York, one asks oneself how it is possible for our reviewing to remain so puerile.” Wilson’s question is more pertinent than ever, given that Birkerts and other self-interested parties are holding up newspaper reviewing as an endangered cultural good, threatened by hordes of amateurs.

In truth, most newspaper reviews, even in major publications, are glorified sales tips. Wilson’s wall of puerility is more entrenched than ever (with some significant exceptions) because far too many newspaper book reviewers are driven by commercial and/or careerist considerations, not by the ideal of disinterested intellectual dialogue. That is why book reviews tend to be bland and self-consciously diplomatic. Independent judgment and intellectual passion — the lifeblood of genuine criticism – will draw authorial and cultural blood. But the ‘professional’ newspaper book critic learns that cutting reviews, no matter how well reasoned, don’t win over friends, editors, and publishers.

Many of our leading critics have admitted as much. The prolific Joyce Carol Oates claims to be so concerned with the future of literary culture that she won’t deign to pen negative reviews. She poses as a champion of books; some in the book industry see her as a heroine. But Oates is the enemy of serious criticism, which earns its credibility by fearlessly discriminating between what’s good and what’s bad. Is there a single book reviewer of substance — anytime, anywhere — who published only admiring reviews? Huzzahs alone – is there a surer prescription for boredom?

Alas, Oates is too big a celebrity to be challenged and her destructive premise, accepted by a number of critics and editors, does much more damage to book reviewing than blogs. Much like the spread of TV’s ‘thumbs up, thumbs down’ mentality, an allegiance to happy talk deforms the public’s idea of what a review is supposed to be. The more criticism reads like advertising, the easier it becomes to replace it with marketing fodder.

Rather than examine how, in this way and others, print book reviewers and editors are efficiently contributing to their own extinction, Birkerts falls into predictable posturing about the democratic “proliferation and dispersal” of book blogs. The irony is that he uses elitist rhetoric to protect mediocrity; newspaper criticism that matters depends on the efforts of authoritative critics whose “unbounded freedom” is edited and vetted for the sake of a common culture.

But this “mattering” requires the existence of a common ground, a shared set of traditions — a center which is the collectively known picture of private and public life as set out by artists and thinkers, and discussed and debated not just by everyone with an opinion, but also most effectively by the self-constituted group of those who have made it their purpose to do so. Arbiters, critics . . . reviewers.

How do the views of this “self-constituted group” appear in newspapers? Intriguingly, Birkerts leaves out editors, but they are the gatekeepers that decide who reviews books in the paper. A week before Birkerts’s piece on the blogosphere appeared, the Boston Globe, where he appears as a book reviewer from time to time, published a critique of Birkerts’s new volume of critical essays Reading Life: Books for the Ages in the Sunday Globe book section. Nothing surprising about that – the “self-constituted group” of critics garners editorial good will and reviews for its books.

The professional reviewer was Daniel Akst, a novelist and critic. His review is polite and pedestrian, though to Akst’s credit he is wary of offical literary criticism (“a genre that is to literature what cholesterol is to arteries”) and offers some flickers of shading in his commentary. Reading between the lines — and that is where you find criticism in many reviews — Akst was obviously irritated by Birkerts’s “sensitive” even “chaste” approach to reading fiction. I sensed a provocative review struggling to get out of a comfy straitjacket, focusing on how the love of reading can be embalmed by excessive gentility.

But, as Birkerts suggests, reviewers don’t have the “unbounded freedom” to let loose. Akst delivers good blurb. Here’s my favorite: Humboldt’s Gift “is Birkerts’s favorite novel, he acknowledges, and this essay alone, with its exquisite mix of heartache and insight, enthusiasm and awe, is worth the price of Reading Life.” Mission accomplished, though “worth the price” is somewhat mummified praise. It would have been more interesting to hear why Birkerts fell short of doing justice to Walker Percy or to have Akst back up his opinion that Henry James’s The Ambassadors “is a work of almost unrelieved tedium.”

James was skeptical of journalistic criticism, but Birkerts believes that reviews accomplish a lot: “by addressing themselves to the idea of a center, by upholding the premise of a public voice, and by hewing to high editorial standards … do a great deal to keep alive the possibility of shared discourse.” Sounds inspiring, but that isn’t what is happening most of the time — reviews are exercises in salesmanship rather than invitations to the rough-and-tumble of debate and evaluation. In this sense, the sad state of newspaper book reviewing is making it harder for criticism to survive — the public accepts what it reads as the real thing.

Wherever Wilson is proved wrong, book reviewing will thrive. Afraid of being squeezed out for good, newspaper reviewers mistakenly figure that peddling books will guarantee survival. Bloggers are under no such death threat; I can think of a number of online writers who would have as many trenchant things to say, pro and con, about Reading Life than Akst.

That is why I don’t agree with Galley Cat’s contention that “Birkerts only widens the gap between the print and online camps — a gap that has no rational reason to exist, since both sides, when viewed in good faith, want exactly the same thing: a viable platform for the wide distribution of serious discussion of contemporary literature.” There is a good reason for that deepening divide; defending and maintaining the status quo is not enough. Where is the evidence that major newspapers are willing to devote the time, resources, and talent to generate meaningful talk about books?

Readers who love books and reviews will go where critics are given the freedom to write with audacity and knowledge, to proffer unpredictable opinions and foster intellectual combat. Online reviewers and bloggers will have to earn the respect of readers with their prose and convictions — and that is a good thing. Laziness and arrogance often set in when authority is placed, like a crown, on the heads of critics in the pages of ‘name’ publications. The challenge for the future will be to create online book review sites that find funding, attract loyal communities, and uphold standards of ethical and editorial excellence.

Tagged: arts-criticism, bloggers, blogs, book-criticism, book-reviews, Books, critics, newspapers, online, Persona Non Grata, reading-life