Arts Remembrance: Emily Remler — The Short Life and Sad Death of a Jazz Guitarist

By Con Chapman

Emily Remler took a particularly clear-eyed view of her work. She didn’t want to be judged by a lesser standard because she was a woman in the overwhelmingly male world of jazz.

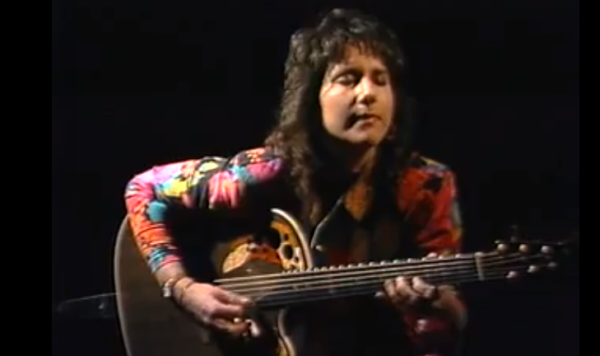

Guitarist Emily Remler — Photo: Facebook.

The death of jazz pianist Geri Allen went largely unnoticed in 2017, a reminder that, however scarce the rewards of a life in jazz may be, the odds of success as anything other than a vocalist in the genre are much longer if you’re a woman. Asked to name a female practitioner of any jazz instrument other than the piano (whose refined pedigree insures that it is always socially acceptable), even avid fans will hesitate and usually come up blank.

Jazz’s history as a lascivious art form may have something to do with it: after all, it was born in Storyville, the red light district of New Orleans, and its practitioners have struggled to shed the image of being the music of the wrong side of the tracks ever since. Bluenoses over the years have railed against both the music in general and instruments on which it is played, particularly the saxophone. The thought of a mother at a suburban bridge club proudly saying “My daughter, the jazz guitarist” accordingly stretches the imagination.

Which made the artistic development of Emily Remler, a jazz guitarist who died of a heart attack in 1990 at the age of 32, that much more remarkable. Remler was born in 1957 (on September 18) in New York, and began playing guitar when she was ten. That chronology would place her squarely in the middle of the mid-60’s flowering of the electric version of that instrument, and she is said to have listened to and absorbed the acid rock style of Jimi Hendrix.

From 1976 to 1979 she attended Berklee College of Music in Boston, where she began to listen to jazz guitarists including Wes Montgomery, Herb Ellis, Pat Martino, Joe Pass, and Jim Hall. Like some other guitarists who start with rock but have an epiphany when they are first exposed to jazz in large doses, she switched styles. In 1978 she was praised by Ellis as “the new superstar of the jazz guitar” when he introduced her at the Concord Jazz Festival; she had learned her lessons quickly and well.

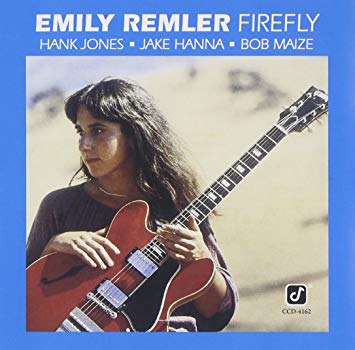

She moved to New Orleans and by 1981 made her first record as a leader, Firefly. Her anomalous status as a woman in jazz brought her some attention in the man-bites-dog theory of newsworthiness, but she shrugged it off. In 1982 she replied to a question along that line from a People magazine writer, saying “I may look like a nice Jewish girl from New Jersey, but inside I’m a 50-year-old, heavy-set black man with a big thumb, like Wes Montgomery.”

She recorded an album with hard-edged guitarist Larry Coryell, Together, but given jazz’s small share of the market for recorded music, she had to play whatever gigs came her way. She was part of the pit band for the Los Angeles version of Sophisticated Ladies from 1981–1982, and toured for several years with samba and bossa nova singer Astrud Gilberto. By 1985 she was at the top of her game, winning Guitarist of the Year in Down Beat’s international poll.

She married Jamaican jazz pianist Monty Alexander in 1981, but the marriage ended in 1984 and, as she put it, after the divorce she “tried to destroy myself as fast as I could.” She began to use heroin and Dilaudid, an opioid medication used to treat moderate to severe pain. Remler became hooked on the high it produces; as described by comedian Rob Delaney in The Atlantic, it feels “utterly wonderful” as it courses through one’s veins. Because Dilaudid is legal, Remler presumably had readier access to it than heroin, either through a prescription of her own or second-hand.

With the exception of Larry Coryell, the male guitarists who Remler admired and imitated weren’t known as heavy users, so it wasn’t a case of hero worship that made her turn to hard drugs. Users of Dilaudid with depression run a high risk for addiction, according to the Prescriber’s Digital Reference, and the drug can cause respiratory distress and death when taken in high doses or in combination with alcohol. In fact, it is approved for use in executions by the state of Ohio.

With the exception of Larry Coryell, the male guitarists who Remler admired and imitated weren’t known as heavy users, so it wasn’t a case of hero worship that made her turn to hard drugs. Users of Dilaudid with depression run a high risk for addiction, according to the Prescriber’s Digital Reference, and the drug can cause respiratory distress and death when taken in high doses or in combination with alcohol. In fact, it is approved for use in executions by the state of Ohio.

One suspects — although it went unsaid at the time — that Dilaudid contributed to the heart attack that killed Remler in May of 1990 while she was on tour in Australia. She can be seen on YouTube videos playing on that tour, and she seems happy, even buoyant. She took a particularly clear-eyed view of her work, and didn’t want to be judged by a lesser standard because she was a woman in the overwhelmingly male world of jazz. Asked how she wanted to be remembered, she responded “Good compositions, memorable guitar playing and my contributions as a woman in music, but the music is everything, and it has nothing to do with politics or the women’s liberation movement.” Her pain was personal, not political.

Since her death, her image has sometimes been subject to airbrushing. The self-described “nice Jewish girl from New Jersey,” who in fact projected an intense persona when soloing, doesn’t appear on the images that accompany two streaming service compilations of her music (“Jazz at Night’s End” and “Sounds of Winter”), nor even on her own album Larry Coryell & Emily Remler on Apple Music. On the first two there are attractive but prototypically WASPy women, one smoking a cigar seductively; on the last, just white type on a black and green background.

For all the progress that her career represented for women on an instrument that is often psychoanalyzed as a musical mimic of an erect phallus, Remler is still viewed as an artist who has to be gussied up for commercial purposes. The double standard remains in effect. Does anybody try to sell records by putting a toupee on bald Joe Pass?

And however much American entertainment may have advanced from the days when the late Valerie Harper, a non-Jew, played Rhoda Morgenstern, Mary Tyler Moore’s Jewish friend, somebody still thinks it’s a good idea to turn Emily Remler into something she wasn’t.

Con Chapman is the author of Rabbit’s Blues: The Life and Music of Johnny Hodges (Oxford University Press).

There’s no telling what kind of monster she would be on the instrument by now if she were still alive. Thanks for helping to keep her memory fresh.

I think she might have continued to get stronger, then plateaued/cooled off/mellowed with age. If you compare young to old Count Basie, for example, he was manic at the beginning of his career but by the end he said as much with a minimalist approach that was almost teasing and comical. There are other examples like him.

Thanks for commenting.

It’s so sad that one of the best guitarists, Emily Remler had to die from drugs.

I’ve watched her tuition videos, she had a conversational style.

Through her recordings, I suppose she’ll always be with us, in one form or another.

I hope she’s still playing, in spirit.

It appears that she took drugs because she couldn’t tolerate the audience

members not liking her music.

As long-time musician/performer myself, I accept that you can’t please all the people all the time.

Also, people are entitled to their points of view.

I’ve never taken drugs.

Always carried Emily’s musical spirit with me. I was so inspired by her playing and instructional video when I was a kid. I’m a percussionist these days clocking up 30 years as a musician and still mention her ideas to students. Such a mature and stylish musician indeed. Sad tale though.

If you listen again to Emily’s later albums ,there is no doubt she would have been successful writing music for movies. This lady was not only a great jazz guitarist-she was a creative musician as well.

I saw Emily play in a duo with a male guitarist whose name I have unfortunately forgotten in a small bar in Manhattan in 1986. It was my first night in NY, indeed my first trip to the USA. I had heard of Emily, but as a UK jazz lover I was amazed to see and hear such brilliant musicians play in such a small venue with such a small audience. Emily was an outstanding talent.

Next night was a Branford Marsalis at the Whippoorwill, but that’s another story.

The Blue Note in the Village, perhaps?

Unfortunately I start listening to Jazz in 1990, as on my first pro gig, the drummer was a student of Jackie McLean! I just “discovered” Emily yesterday… she’s so amazingly gifted and I also wish she had been with us a bit longer so we could have gotten more of her Love! RIP

Bright star burned out way too young. She was a traditionalist for much of musical output in the 80’s, but in a way that complimented her influencers, but was also pointing ahead. Her last few albums seemed to be shifting her into newer territories. I once worried that she might be heading into Smooth Jazz territory but I don’t think that would have satisfied her and she would have kept evolving. Her compositions (Catwalk, Mozambique, Carenia) are so underrated and underplayed, I hope there is a bigger rediscovery of her songs at some point. In addition, she swung as hard as any guitar player past or present, her sense of time is amazing and something all musicians should emulate.

There needs to be a rerelease of all her material. The CD’s and albums are often hard to find, and pricey. Sonically they came out in the early days of digital recording and some of her stellar playing is lessened by the poor sound quality of these records.

Andy, I agree that her recordings need to be re-released. Most of her music is hard to find and sometimes ridiculously expensive.

Emily’s passing was tragic and a gut-punch to the Jazz Guitar Community around the globe. Like Matt Stonehouse mentions above, her video series also left a big impression on me and I use her concepts to this day. I also saw her and Larry play at a small Jazz Club in Montreal when I was younger and it was a wonderful pairing of two similar souls doing what they loved to do best…at least that was my impression. Thanks for the remembrance.

Lyle Robinson

The Jazz Guitar Life

I only discovered Emily Remler about six months ago, but I love her music. I have been searching to hear all she did in her brief but productive career. She was brilliant. I didn’t think of her as anything else other than a genius musician who never got enough credit while alive. It breaks my heart to read of her tragic life and the loss of her talent to the world. She will grow in importance with the years, absent of her continuing her progression on the guitar.

I think Emily Remler and Kenny Burrell. are 2 of the most under-rated guitarists of all time. Yes, I’m sure the opioids

hastened Emily Remler’s death and I can see why one would draw that conclusion. However, according g to several sources, her cause of death was heart failure. I ask that, instead of knee jerk judgements about what its cause, several sources mention that cleaned up or was in the process of so doing. Unless we were there, either in person or the medical examiner who determined the cause of death, we truly DON’T know. With that in mind, let’s not be hasty in our judgement.

I can understand why substance abuse was an issue for her. The music industry can be brutally unkind to even those who have ascribed advantages and the support of their communities. I know it’s at least 3-5x more difficult being a woman. You see I have a long time friend who’s a PHENOMENAL musician who’s a woman. For years, I’ve watched her struggle. I’ve watched her get passed over for gigs by dudes with a fraction of her ability. I’ve seen the resentment from insecure males should the audience applaud her efforts more than theirs. Their disrespect ranges from the obvious to the more subtle acts such as exclusion, (not making eye contact during group conversations..as if she were an unseen ghost

…UNLESS OF COURSE, there was criticism to me meted out. Then they made CERTAIN she received full eye contact throughout much of the conversation. Then they try to deny it. My friend had a substance abuse issue for a number of years. Fortunately, health problems and a near fatal overdose and the support of a loving husband and a few caring friends, she managed to get clean. Just as important she’s still playing and being defiant towards those who hate. But in the back of my mind, I believe she’d be more respected, she’d be at the top of the list for the best paying gigs and she’d have less frustration and financial worry if she were a man! I admire my friend in that she’s honest and incredibly resourceful and resilient. It’s easy to see why Emily Renner turned to drugs to dull the pain of the injustices I know she endured throughout her short life time. While women have made considerable progress over the past half century, they still have a long way to go before the playing field is leveled.

Your story resonates with me, and I understand your friend’s frustration entirely. Sharing that story in this context is useful.

All your observations are valid; indeed, we should not pass judgment. Emily Remler was indeed a talented artist and it is a terrible shame that she did not endure.

Hopefully, her story will serve as a cautionary tale to other young talents.

I wish I saw this review back when it was written two years ago. Two real oddities: streaming services online regularly use unrelated images (stock photos) as a cost-saving device. Men and women alike. It has nothing to do with gussying up Emily Remler. And the tiny online ads for streamed music have nothing to do with album cover art. Old albums of less than handsome male jazz instrumentalist often took the star right off the cover, replacing them with female models to romanticize their image, or just to avoid a homely guy’s pic blown up to LP size. Photographers used shadows and angles in arty ways to make male jazz artists lookcool. Most male singers were pretty nice looking, but Mel Torme was a real challenge for photogs.

Secondly, throwing in a TV sit-com star of the 1970s and ’80s (Valerie Harper) into the discussion of the female image in instrumental jazz… that is one weird choice! How is that about changing a female artist’s image to fit the marketplace — an actor is always playing a part! I am Jewish, yet I never thought having a non-Jew play a Jewish character was antisemitic, as long as the characterization wasn’t negative, and as long as Jews were being employed (in general) for starring roles. And does that mean Jews can’t play goys? Having Italians in makeup playing Native Americans in the ’50s… okay, I get that that is incorrect. But Valerie Harper as Rhoda? Gimme a break!

One further series of thought on an issue brought up in the comments… I question the rumor that Emily Remler turned to drugs because audience members didn’t like her. That makes no sense: I can’t imagine jazz-loving audience members in small clubs and intimate concert halls vocally, openly disliking her! What was far more likely is what Andy wrote in his comments — that it was a shame she played for such small ‘crowds.’ I saw her in the mid or late ’80s at the old (very small) Cambridge MA jazz club 1369 (the name-source of the present-day coffee joints). There was a decent but not packed audience, and it was an insanely small club, so… not many people. But they were, of course, enthusiastic. I chatted with Emily afterward. She seemed in an okay mood. But then a person (connected to the club, perhaps?) whispered something to her, and she got up from the bar-stool and excused herself, abruptly, but with a smile. She went to the basement. I later learned their was drug-trafficking going on there, not for the general public, but “for” musicians who used. As I recall, her 2nd set was just as good as the first. Emily was playing mainstream jazz guitar in her brief career, and however excellent she was (ans she was!) it was amped-up fusion jazz/rock/etc. that played the big halls in the ’80s. So, I can well imagine she was somewhat depressed that her audiences were small, and so was the money. I can also, upon reading about her, believe she was upset with the end of her marriage to Jamaican pianist Monty Alexander. I have found in life that childhood woes, romantic split-ups and divorces and infidelity and betrayal… not feeling loved and respected…those are causes for depression and (maybe) a dependency on drugs. In music, one-night stands, exhaustion, and easy access to drugs also are factors, of course. But since I know nothing about the inner-life of the superb jazz guitarist Emily Remler…I prefer to accept the Wikipedia info… that she had a heart attack, her heart possibly weakened by her few years as an addict, and the labor of getting off drugs near the end of her tragically short time on this earth. If she was around in the 50s, I bet she’d have attracted more fans. The ability to play like her was, and I say this as an agnostic, heaven-sent.

I just learned about Emily today her playing was really good her aurora was bright and she was beautiful she is forgotten about but I hope more people shine light of her work may she Rest with God

Ps someone please get here records on streaming platforms please

M. Hicks

Thank you for this wonderful article.

She started listening to those jazz guitarists when she was 16, not when she was at Berkelee. Just a friendly correction. This is something she said herself in an interview, that she made a commitment when she started listening to Wes Montgomery at age 16. I can find it if you’d like.

A fine article Con.

So very sad. I saw Emily in Brisbane at the Travelodge Hotel jazz bar in 1990 efore she flew to Sydney. The rest is history.

Every time I play her album ” East to Wes “, I have a tear for a very fine artist who departed way too early.. Her version of ” Softly, as in a morning sunrise ” is exquisite.

You’re still being missed Emily.

Don’t know what I can write that hasn’t been written yet in a positive manner. She was a well respected musician from what I gather.

I recently heard of her on RealJazz – Sirius radio.

I’m glad that they are keeping her alive. Really do enjoy her playing. Her dynamics are superb.

(Sigh)

Heart attack?? Drug overdose. She had a long-term habit.

That long term habit will eventually kill you

“Remler is still viewed as an artist who has to be gussied up for commercial purposes.”

Easy for you to say, lol! Welcome to the awareness of the patriarchy brother!

I didn’t know who she was until I heard her play “Some Other Sunset” on David Benoit’s album. So exquisite and mature and melodic and sophisticated. She was a gift to the music world who shone brightly if briefly. And a trailblazer for women in jazz. She worked really hard at it. She and Roy Hargrove are the 2 jazz musicians who died young and who I regret not having seen play live. I hope that other women might by inspired to pursue their jazz dreams because of Emily.