Classical CD Reviews: Uri Caine’s “The Passion of Octavius Catto,” Bernard Hoffer Chamber Music, and Igor Levit’s “Encounter”

By Jonathan Blumhofer

Uri Caine’s score about the life and murder of a 19th-century civil rights icon is direct and potent; touching documentation of Richard Pittman’s advocacy for the inventive composer Bernard Hoffer and a demonstration of the sheer musical excellence of Boston Musica Viva; Igor Levit’s keyboard playing is dynamic, precisely articulated, vividly felt, and beautifully voiced.

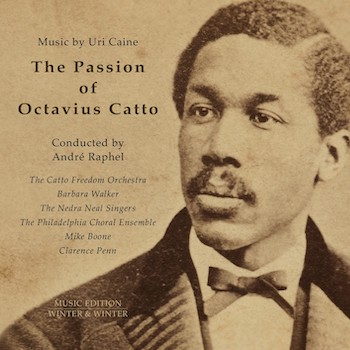

Uri Caine’s The Passion of Octavius Catto isn’t a long piece: it only lasts about half-an-hour. But the score, which relates the life and murder of the 19th-century civil rights icon, packs a punch.

Part of that, surely, owes to the fact that Caine’s score is so direct and potent. Much of the writing in it draws on gospel and the blues. “No East, No West,” which uses texts from Catto’s speeches, drives with the conviction of an old gospel standard. So does the concluding “The Martyr Rests.” In between comes the call-and-response “Change” (a setting of another Catto speech) and the hymn-like “The Amendments,” which tells of Pennsylvania’s struggle to ratify the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the Constitution.

Other types of music also intrude. The evocation of the burning of Pennsylvania Hall in 1838 is full of unsettled rhythmic lines as well as sudden juxtapositions of character and gesture. “The Baseball Star of 1867” culminates an a woozy, Ives-ian collage (including, yes, snatches of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame”).

Caine and his trio (bassist Mike Boone and drummer Clarence Penn) are involved in the proceedings. But their parts are almost unexpectedly small – or subsumed into the larger musical storytelling.

As a result, the Passion’s vocal solos and choral writing loom large. In the former, Barbara Walker proves phenomenal: in character, mood, tone, and spirit, she fully embodies this music and story; it’s not too much to say that Walker doesn’t so much sing the piece as lives it.

The choral parts, sung here by The Nedra Neal Singers and Philadelphia Choral Ensemble, are mighty, full of spunk and feeling. Indeed, it’s a tribute to the excellence of the vocal contributions that the score’s sometimes wordy texts come across with such astonishing clarity.

Conductor André Raphel presides over it all, energetically leading the Catto Freedom Orchestra. The group acquits itself particularly well in the slashing “Prologue” and dissonant, chaotic “Murder” scene.

Gripping as the music is, the Passion’s story – of a Black man cut down in the prime of his life, in broad daylight and before witnesses; his killer absolved of responsibility for his murder – is unsettlingly familiar.

That, nearly 150 years on, this is the case is horrifying. True, in Caine’s score, there’s a vision of light at the end of the tunnel. To be sure, it’s a rousing one; yet, scrolling through the daily news, it’s clear the United States hasn’t gotten there yet. This is a piece that’ll make you pray – and, better, work – to see that we arrive at that destination, and sooner than not.

It’s safe to say that Boston Musica Viva’s (BMV) new album, A Celebration: Chamber Music by Bernard Hoffer, was a labor of love. To be sure, few ensembles have championed the now-86-year-old composer with greater enthusiasm. That’s partly a testament to the devotion of Richard Pittman, BMV’s founder and conductor, to Hoffer. But it’s also a reflection of the craftiness of Hoffer’s writing, which, as this generous double-disc release demonstrates, is top-flight.

It’s safe to say that Boston Musica Viva’s (BMV) new album, A Celebration: Chamber Music by Bernard Hoffer, was a labor of love. To be sure, few ensembles have championed the now-86-year-old composer with greater enthusiasm. That’s partly a testament to the devotion of Richard Pittman, BMV’s founder and conductor, to Hoffer. But it’s also a reflection of the craftiness of Hoffer’s writing, which, as this generous double-disc release demonstrates, is top-flight.

Remarkably, the oldest piece here is the 2015 ballet Paul Revere’s Ride. I was strongly impressed hearing its world premiere and the present document, taped nearly two years later, holds up to my recollection: by turns ingratiating and familiar, but also turbulent and probing – music for a children’s concert that doesn’t gloss over darkness and unease.

An even more agitated aspect marks Hoffer’s 2016 Lear in the Wilderness, a setting of King Lear’s Act 4, Scene 6 ravings in the eponymous play. Here, they’re delivered with clarity and menace by baritone David Kravitz. True, a moment or two of relief passes by (including a surprising, brief Cole Porter-ish episode), but Hoffer’s writing is largely stormy and gritty.

But to suggest that Hoffer’s music here is all grim and troubled is inaccurate. Ultimately, it loves to play and brims with personality.

The latter qualities comes across amply in the pair of Concerti di Camera presented here.

The earliest, 2016’s Concerto di Camera IV, features clarinetist William Kirkley dispatching solos on three different types of clarinet (B-flat, E-flat, and Bass clarinet) with aplomb. Its four movements make gleeful references to a variety of forms and styles, culminating in a playful, jam-session-like finale called “Tomfoolery.”

There’s a bit less of an overtly jazzy feel in Hoffer’s Concerto di Camera V (written between 2017 and 2019), but flautist Ann Bobo is magnificent, whether she’s playing bass flute, alto flute, (the normal) flute, or piccolo. Likewise terrific is her partner (and frequent accompanist in the piece), percussionist Robert Schulz.

Also included on the album are 2016’s Musica sacra – a reimagining of part of a Mass setting by Claudin de Sermisy – and 2017’s Musica profana. The former alternates quotations of the Claudin Mass with instrumental “commentary” that runs the gamut from medieval devices to contemporary gestures. It’s a real ear-catcher: you never quite know which direction the music will turn next or how familiar themes and motives might be recontextualized.

Both Musica sacra and Musica profana overflow with counterpoint – Hoffer’s scores are never dull or inactive, especially when they shift into jazz mode, as the finale of Musica profana does (brilliantly, one might add). Nor does his writing ever feel rhythmically dull: the title track, 2019’s A Celebration, is driven by motoric rhythms and radiant colors.

In all, this is a terrific release. BMV’s playing is flexible and fully in tune with Hoffer’s style. The album’s engineering is, likewise, excellent, BMV’s sound being consistently natural and resonant.

Ultimately, we’ve got a touching documentation of Pittman’s advocacy for Hoffer, a wonderful demonstration of the sheer musical excellence of BMV, and a deserving tribute to Hoffer’s inventiveness as a composer.

Early in the pandemic, Igor Levit was one of the first classical musicians to take advantage of the possibilities of streaming live performances – in his case, concerts from the pianist’s apartment in Berlin. His new album continues in the vein of those early programs, with their strong desire to forge some sort of meaningful personal connection (albeit remotely), pairing arrangements of music by Bach and Brahms by Ferrucio Busoni and Max Reger, as well as Morton Feldman’s last piano piece, Palais de Mari.

Throughout, Levit’s keyboard playing is dynamic, precisely articulated, vividly felt, and beautifully voiced.

His account of Busoni’s arrangement of Bach’s 11 Chorale Preludes range from probing (in “Komm, Gott, Schöpfer” and “Nun komm, der Heiden Heliand”) to boisterous (“Nun freut ech, lieben Christen g’men” and “In dir ist Freude”), searching (in “Ich ruf’ zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ”) to serene (“Herr Gott, nun schleuß den Himmel auf”).

In Busoni’s adaptation of six of Brahms’s Chorale Preludes (originally for organ), Levit’s playing never gets lost in the denseness of the music’s voicings. Granted, these are rather sober works, overall, but Levit teases out their lyricism (“Es ist ein Ros’ entsprungen” is conspicuously fine) and makes particularly touching work out of the second arrangement of “Herzlich tut mich verlangen.”

Reger’s adaptation of Brahms’s Four Serious Songs is almost staggeringly literal; and, as a result, they’re particularly thickly voiced. Yet Levit gets each of them to sing and, in the fervent moments especially, imbues the writing with plenty of warmth.

The opening “Denn es gehet dem Menschen” is impressively dexterous, both rhythmically and texturally. So is “Ich wandte mich, und sahe an,” the majore sections of which float. “O Tod, wie bitter bist du” is nicely weighted, its coda radiant. And the concluding “Wenn ich mit Menschen” evinces a mighty sense of shape, not to mention a beautifully restrained central section.

A well-shaped traversal of Reger’s own Nachtlied leads to the Feldman, whose spare textures, repetitive gestures, and expressive unquiet works remarkably well with everything that’s come before. Levit’s performance of it is perfectly fitting: unhurried, questing, and sonorous.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.

Tagged: Albany, André Raphel, Bernard Hoffer, Boston-Musica-Viva, Igor Levit, Richard-Pittman, Sony Classical, Uri Caine

[…] Classical CD Reviews: Uri Caine’s “The Passion of Octavius Catto,” Bernard Hoffer Cham… […]