Streaming Docs — Autumn 2019

By Neil Giordano

Wondering where to find the best documentaries on digital platforms? Look no further.

Now that autumn has finally arrived and the days are becoming shorter, here’s a few selections from the streaming landscape that are perfect for dark, chilly evenings of viewing nonfiction film.

Streaming-only

A scene from “American Factory.”

American Factory (Netflix)

Directors Julia Reichert and Steven Bognar have spent their filmmaking careers exploring how people work in America, so American Factory comes as no surprise. The Chinese translation 美国工厂– indelibly attached to the English title — is what sets their new documentary apart from their earlier homegrown examinations. By 2019, the effects of globalization on the economy are impossible to ignore. At this point, we can begin to see where it leaves us in the US, and that raises important questions: what does it mean to be an American worker in a global economy? And what does our culture of work mean to Americans — practically as well as spiritually?

Reichert and Bognar revisit the story they began in 2009’s The Last Truck: The Closing of a GM Plant (available on Amazon), which observed the reactions of autoworkers when their factory closed in Moraine, Ohio. In the years that followed, the facility was purchased by Fuyao, a Chinese auto-glass manufacturer. By 2016, the plant employed 2,000 American workers in both managerial and floor jobs (some who’d worked at the GM plant), but now under the banner and culture of Chinese ownership. The project was watched closely by politicians, hoping to laud it as a triumph of the new global economy. American Factory tells the story from the inside, dramatizing a unique culture clash.

The film’s visuals and sharp editing detail the surface fissures that will eventually influence practical decisions. Early in the film, a group of American managers visits the Fuyao headquarters in China for a planning meeting. The Chinese men and women, mostly stone-faced and trim, dressed in handsome suits, sing their company’s quasi-nationalistic theme song. Then their pudgy and smiling American counterparts saunter into a conference room in ill-fitting polo shirts, one inexplicably wearing a Jaws T-shirt. When the Americans study the Chinese production process, we share their reaction of headshaking awe: the Chinese workers line up with military precision, in identical uniforms, chanting slogans. During the sequence, a quick glimpse of one of the American’s bulging tattooed arm says it all. Our first impression, and one that persists, is that the Americans are a jovial bunch, but undisciplined and inefficient because of their very American individuality. The Chinese, on the other hand, dismiss the self (at least at work); they are dedicated to the factory as if it’s their nationalistic duty. The Americans’ faces say it all: “this will never fly in Ohio.”

And as production gets underway in Ohio, the problems quickly pile up. The American workers cannot meet the quotas demanded by the Chinese. What’s more, the quality of their work is just not up to snuff. Simultaneously, the Americans on the factory floor complain that break rooms are insufficient and safety violations are being ignored. Also a harsh reality — that their hourly wages are half of what they once were at the GM plant — begins to sink in. One American manager, who speaks fluent Mandarin and sympathizes with the Chinese owners, wonders, maybe only half-facetiously, if they should duct-tape the American workers’ mouths shut so they’ll work harder.

Meantime, we are given more glimpses back in China of the factory culture to which Fuyao is accustomed: 12-hour shifts, no breaks, forced overtime, no vacations, and low pay are all taken for granted as part of the job. Some workers have left their homes and families in rural China to land these hard-to-find jobs, so they are acquiescent to the inherent dangers and exhaustion of the assembly line. Clearly, the filmmakers were only given access in China to what Fuyao wanted them to see. Thankfully, they include one possibly unauthorized sequence of Chinese factory workers in their apartment, briefly reminding us that these are not automatons completely controlled by their employer, nor are they as content as they might seem to be on the factory floor.

The movie is at its most successful in showing what Americans have come to take for granted after a century of labor reforms, but is now being eroded — not by American CEOs, but by the demands of globalism. American Factory ends with a union-organizing effort at the plant to preserve the culture of work the Americans had enjoyed a decade earlier. The effort might spell doom for the Fuyao experiment once and for all. Still, the gesture begs a larger question: are unions in various countries prepared to fight in a global economy? The most cutting irony at play in American Factory is plain evidence that our brand of capitalism pales in comparison to the profitable authoritarianism created by the Chinese economy. The Communist Chinese have come up with the ultimate free market system — free of any unprofitable “distractions” from unions or safety protocols or environmental regulations. Younger Americans might begin to wonder (particularly those familiar with working conditions in Amazon warehouses) if this is their future, as well.

A scene from “Roll Red Roll.”

Roll Red Roll (Netflix) Recent years has seen the invention of a dismaying new subgenre of documentary — the true crime teenage rape narrative. Although, perhaps counterintuitively, the form may be a sign of progress. Few of these tragic stories escape the comfortable confines of local newscasts, where they are greeted with defiant headshaking and anodyne clichés about social pressures on males and females mouthed by “experts.” Now we have documentaries coming along that are willing to look, honestly, at the frightening roots of rape culture and its big brother, toxic masculinity.

Roll Red Roll manages to tell its story without directly confronting the accused or the accuser. Instead, it looks at the widening gyre of anger that consumed Steubenville, Ohio, in 2012 after two football players assaulted an unconscious girl in full view of other attendees at a party. Drawing on interviews with fellow students and parents, along with the inclusion of disturbing footage filmed during the assault by another athlete, the film illustrates the almost incomprehensible complicity of bystanders before, during, and after the attack. Moreover, it takes a good look at a new layer of horror; how social media amplifies the original event, exploiting (and expanding) the trauma and revving-up the victim-blaming. Still, Roll Red Roll also shows that, in this case specifically, it is the Internet (in the form of hacktivist collective Anonymous) and the social media record (from partygoers’ phones and text chains) that leads to the boys’ convictions.

Untitled Amazing Johnathan Documentary (Hulu)

I’d like to think that this film is a joke aimed at the professional documentary world, title and all. It plays around with a variety of ethical issues that bedevil nonfiction filmmaking. It also pokes well-earned fun at current talk about the “golden age of the documentary.” Yes, there is a glut of fine films about captivating, provocative subjects. But we have a pileup of films trying to explore similar topics (Fyre Festival, anyone?). Still, it could be that director Ben Berman — known mostly for his television comedy work — may have intended the project to be a serious portrayal of its subject, John Szeles, also known as the Amazing Johnathan, whose magic-comedy-performance art act was a recent popular attraction in Las Vegas and on television variety shows.

After Szeles had been diagnosed with a heart condition that gave him a year to live, Berman decided to film the performer during his “farewell tour.” Szeles’s act involves him pulling off various illusions. And this notion of fakery offers a clue to the problems Berman encounters in making the documentary: can we take anything Szeles says at face value? Is he even really dying? Is anything about this film real? And (spoiler alert) are there really three other documentary projects in production about Szeles? Berman tries (pretty clumsily) to escape these conundrums, but his style is hamfisted, to say the least. As an examination of the challenges of ethical filmmaking (if that is what this is), Untitled Amazing Johnathan Documentary comes off as just another sleight of hand.

Recent gems and award winners

A scene from “Bisbee ’17.”

Bisbee ’17 (Amazon) and Kate Plays Christine (Kanopy, Fandor)

The recent films from writer-director-scholar Robert Greene blend nonfiction with reenactments staged in a highly self-conscious style. In the process, they explore the potential and limits of the traditional documentary form.

Bisbee ’17 (2018) revisits vicious antiworker doings in 1917 in the border town Bisbee, Arizona. Local law enforcement colluded with a copper mining company by pitting citizens against one another in order to break a miners’ strike. Hundreds of armed townspeople formed a posse to help illegally deport more than 1,000 striking miners, many of them their neighbors and relatives. They corralled the miners onto a local ball field and then loaded them onto railroad cattle cars, warning them to never return and sending them off into the parched Southwestern desert. The story was covered up at the time by local officials and throughout the century that followed. Bisbee repressed the incident — it was something never to be talked about.

By design, Greene’s film does not simply return to Bisbee and reenact the events 100 years after the crime. He casts all the roles with current citizens of the town, which sets in motion an act of moral reappraisal; many of the “actors” are descended from people on both sides of the event. Some know little of the stain on their town’s history and find themselves cast in roles they’re not sure they want to play; some of the participants can’t help but compare their 1917 selves with who they are today. Even more compelling is the fact that a majority of the miners in 1917 were immigrants from over 30 different nationalities. The deportation was clearly an act of nativism, as well as anti-unionism, although some current residents cannot admit that truth. Emotions eventually spill over between history and reenactment, as the “actors” begin to embrace their parts while others draw the inevitable connections to present-day politics. One reenactor, a young Mexican American man, reflects on the fact that his mother was deported to Mexico, pausing to note the ways that the past attitudes of hatred continue to linger.

A scene from “Kate Plays Christine.”

Kate Plays Christine (2016) works on a smaller canvas, but that only intensifies the power of of Greene’s method. Actress Kate Lyn Sheil is enlisted to play the lead role in a purported biopic of Christine Chubbuck, the Florida newscaster who infamously took her own life on air in 1974. But the only film about Chubbuck being made is Greene’s self-contained meta-documentary about Sheil herself. Sheil’s preparations for the role create an illuminating portrait of Chubbuck and the reasons behind her suicide, while also raising a host of issues related to the ethics of documentary filming, not to mention the voyeuristic and sensationalist tendencies of media culture. Even more meta is a sly commentary on the performative nature of both Chubbuck’s death and of Sheil’s role as an actress on screen. (Greene’s previous film, Actress, examines ideas of self-performance and artifice in further depth.) Sheil intensifies the gendered threads of Chubbuck’s story — her feeling that she was an “old maid,” the disrespect she felt as a female journalist in a male-dominated field — and compares her life with that of Christine’s. Midway through, Kate Plays Christine’s scenes begin to unfold in duplicate — first with Kate in her street clothes, then refilmed with Kate in costume and wig as Christine. The effect is to blur the lines between the two women’s experiences.

The ambition is admirable, but there are flaws. The lengths to which Greene goes in his reenactments means that the film meanders. All the multiplying artifice wears away at the strategy’s dramatic payoff: for instance, the casting of Chubbuck’s colleagues, friends, and family feel extraneous as the scenes pile up. Still, elevated by the strength of Sheil’s acting and Greene’s hall-of mirrors stylizing, the film asks a powerful question: Why do we make and watch stories like Chubbuck’s? Arts Fuse review

The Brink (Hulu) Former Trump administration political consultant Steve Bannon is given more time in the limelight, which he obviously savors. But Alison Klayman’s mostly observational portrait reveals fissures in the strong man’s brash arrogance. Picking up shortly after his resignation from the White House in 2017, we see him embark on his pursuit of “The Movement,” his self-professed quasi-populist worldwide effort to unite elements of various far-right factions. As he works to promote anti-immigrant and anti-Islam policies under the guise of “economic nationalism,” Bannon manages to ally himself with dubious figures that some of his right-wing European allies are afraid to embrace. And, in typical Bannon style, he denies he’s doing anything underhanded, shunting aside talk about moral responsibility while standing, without skepticism, by his methods. He embraces doublespeak at its worst, which he clearly feels is valid and necessary when spreading his dogma.

Not one for “gotcha” moments, director Klayman instead takes a lighter approach, mostly letting Bannon’s relentless self-righteousness catch up with him. As time goes on, and the 2018 midterms approach, the bombast wears thin. Bannon’s denial that he is equating “globalism” and anti-Semitism ring increasingly hollow (and his defensiveness becomes more pronounced). Particularly amusing are his constant screeds against the world’s “elites” and his identification with the white working-class “deplorables” (a term he uses proudly) while he flies private jets and inhabits luxury hotels, paid for by shadowy Citizens United-enabled dark money. (When Klayman asks directly who funds his movement — and who doesn’t — he says, “I wouldn’t take foreign money,” which seems unlikely given his international ambitions.) Nonetheless, Bannon comes across as an adept propagandist, at one point wondering aloud “What would Leni do?” (as in Leni Riefenstahl, the Nazi filmmaker). The Brink doesn’t quite go so far as to show him as ineffectual. This is a vision of a man self-obsessed: a gasbag whose inflated sense of his place in history doesn’t match reality.

A scene from “Icarus.”

Icarus (Netflix) The 2018 Oscar-winner is one of those films that wends its way along a circuitous path before it stumbles upon its real subject. Filmmaker Bryan Fogel’s original intent was to examine the effect of performance-enhancing drugs on athletics by using himself as a test subject. He would use various PEDs and avoid detection and see if it would help him succeed in amateur competitive cycling. But his investigations bring him into contact with PED expert Grigory Rodchenkov, nominally the head of the Russian government’s anti-doping efforts. In reality, Rodchenkov is a major player behind Russia’s efforts to circumvent doping rules. He unaccountably shows off to Fogel, quite openly, all the dubious but brilliant ways there are to cheat the system.

In the midst of Fogel’s investigations, the World Anti-Doping Association (WADA) has begun its own inquiries, and that leads them straight to Rodchenkov. He soon he calls Fogel in a panic, worried that his countrymen (and Vladimir Putin) are after him. The drama comes off as slightly manufactured at times — besides that, there are numerous other ethical quandaries at play here — regarding the athletics as well as the filmmaker. Fogel is called before the WADA inquiries, where he defends Rodchenkov as a good man, victimized by Putin’s overreach. The director never makes us believe that, and Rodchenkov himself doesn’t help his own case either. He appears to be quite content to stand in front of the cameras and be the center of attention (in the film as well as in the inquiry). Can we believe either of them? Omitted from the film are answers to Fogel’s initial question — is cheating actually cheating? This story may not quite be an Orwellian as Fogel would like us to thing. (At one point, he even quotes from 1984.). Still, this is a smart and entertaining ride, with Rodchenkov a memorable, larger-than-life character despite all the ambivalence he generates.

Amazing Grace (Hulu) Aretha Franklin sings the hell out of gospel music and it is filmed by Sydney Pollack during a 1972 performance that led to her biggest-selling album. If that doesn’t get you excited in seeing this long-shelved project, nothing will. Put together for the big screen in 2018 — shortly after Franklin’s death and 10 years after the director’s — the scenes here present a different side of the performer, one more concerned with entering Kingdom Come than in reigning as the Queen of Soul. Arts Fuse feature

Documentary Classics

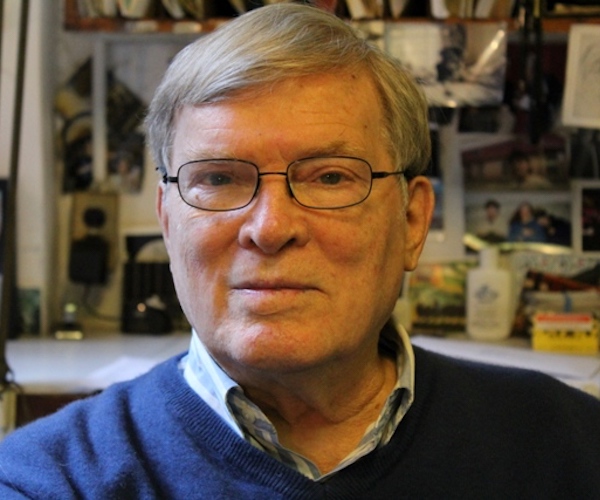

The late D.A. Pennebaker — his documentaries dovetail idealism and messy reality.

D.A. Pennebaker: In Memoriam

The passing last summer of one of the 20th century’s great documentary filmmakers should lead you to viewing his finest works. Two films stand above his others, all of which deal with the interactions between idealism and messy reality. The highly influential Don’t Look Back (Criterion) sets the standard for musical biography and shaped our perception of the burgeoning iconoclast that was Bob Dylan in 1965; The War Room (Criterion) provides an inside look at the 1992 presidential campaign of Bill Clinton. An ode to the end to the Reagan era, the film made “stars” of future politico operatives/talking heads James Carville and George Stephanopoulos, as it took us into the hard-nosed machine behind the campaign’s liberal ideals.

Also available on the Criterion Channel: Pennebaker’s first film, Daybreak Express, a paean to New York City with a Duke Ellington soundtrack, plus the original Monterey Pop, now available in a version that features outtakes of the acts at the festival, including complete performances by Otis Redding and Jimi Hendrix.

Missing in action in the streaming world is Original Cast Album: Company, a glimpse of musical wizard Stephen Sondheim at work in 1970. As an ersatz substitute, you might try the ruthless parody of Company created by the IFC television series Documentary Now! (Netflix). Pennebaker himself was apparently a good sport — he not only showed up for the film’s 2018 theatrical premiere but laughed along with the rest of the audience at the send-up of his trademark filmmaking style.

Previously reviewed on The Arts Fuse and now streaming

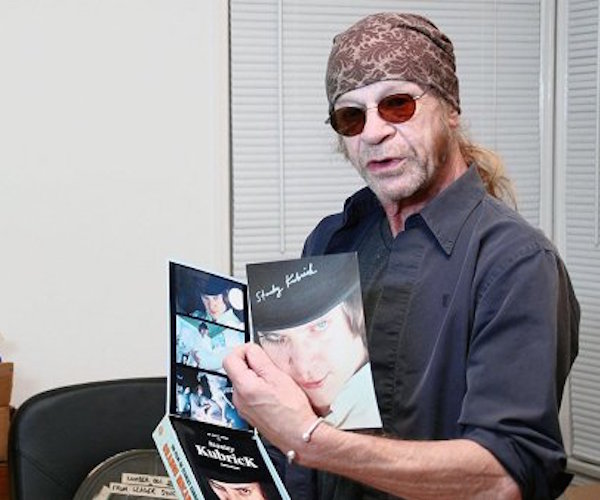

Leon Vitali, the subject of the documentary “Filmworker.”

FilmWorker (Netflix) A tribute to the unheralded Leon Vitali, right-hand man to legendary director Stanley Kubrick for 30 years. The film chronicles the maddening reality of working for a notorious control freak. Arts Fuse review by Gerald Peary

Hale County This Morning, This Evening (Amazon) A beautiful montage that depicts the lives of young people in the contemporary Black Belt, a 2018 Oscar nominee. Arts Fuse review by Neil Giordano

Hail Satan? (Hulu) A seriocomic portrait of the Satanic Temple of America, examining its transformation from a trolling performance art phenomenon to a legitimate political force in American discourse. Arts Fuse review by Peg Aloi

Tea with the Dames (Hulu) Actress Joan Plowright chats with Eileen Atkins, Judi Dench, and Maggie Smith about their distinguished acting careers and lives. Arts Fuse review by Tim Jackson

Neil Giordano teaches film and creative writing in Newton. His work as an editor, writer, and photographer has appeared in Harper’s, Newsday, Literal Mind, and other publications. Giordano previously was on the original editorial staff of DoubleTake magazine and taught at the Center for Documentary Studies at Duke University.