Television Review: “Deadwood: The Movie” — History’s Train Pulls into the Station

By Lucas Spiro

Of course, history has not come to Deadwood to douse the smoldering embers of the past, but to supply more kindling.

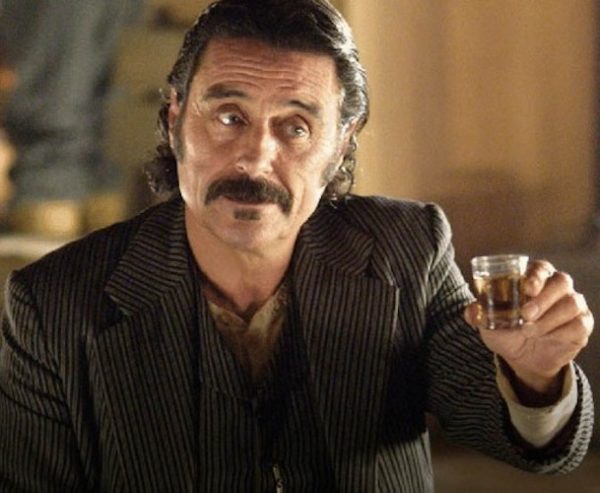

Ian McShane in “Deadwood: The Film.”

The steam engine has chugged into Deadwood and, with it, the arrival of modernity and a deserving end to David Milch’s frontier drama Deadwood. Trains have played a significant role in cinema since August and Louis improved the cinematograph and The Great Train Robbery hit nickelodeons, wedding an illusion of the speed-obsessed present (and intimations of a speedier future) with images of a slower-paced, shoot-em-up past. It is no wonder that Deadwood: The Movie begins with the sound of steam and piston-driven wheels barreling headlong toward the immoral heart of American destiny. History is wheeling into the station.

Of course, history has not come to Deadwood to douse the smoldering embers of the past, but to supply more kindling. “Ten years gone approaching that self-same hill I thought to lay me down and rise no more,” muses Calamity Jane (Robin Weigert) over the sound of the steam engine’s whistle, as she rides the same trail into camp on which we first saw her in episode one. These words seem to come straight from Milch’s mouth, who wrote the film’s screenplay while grappling with his recent Alzheimer’s diagnosis. (The movie was made nearly thirteen years after the show’s premature cancellation.) For someone who has not been able to finish a project since NYPD Blue, it is a kind of merciful justice that this film exists at all. This time, though, Jane’s (and Milch’s) prophecy of finality may come true.

The film takes place ten years after the events of the season three finale and directly links the narrative to the unresolved conflicts of that episode. We last saw Al Swearengen (Ian McShane) on his knees, scrubbing at a bloodstain on the office floor of his brothel, The Gem Saloon, having just murdered an innocent prostitute to satisfy the bloodlust of villainous magnate George Hearst (Gerald McRaney). He needed to kill the girl in order to protect the former prostitute Trixie (Paula Malcomson) from Hearst’s yen for vengeance. Hearst has returned to Deadwood, now a California senator, to commemorate South Dakota’s statehood and develop his significant financial interests. He learns Trixie is still alive and finds that his business plans are blocked.

Deadwood: The Movie is intended to be a standalone, and it works on that level. A series of flashbacks to the events in the final episode assist the uninitiated, but they are not narrative crutches or particularly intrusive. The real audience for this film is, of course, the fans who felt cheated by the decision to cancel the show in the first place. Perhaps these are the same followers who felt fleeced by the ending of Game of Thrones, a series that clumsily thrashed its way toward a poorly written finale — with the approval of the same media company that pulled an untimely plug on Deadwood.

Milch seems to understand that the chance to “finish” Deadwood is really a false opportunity. Fans will know there will always remain so much undone, unsaid, and unwritten. Milch couldn’t touch on all of the various threads he wove into the series, or he would have introduced too many superfluous elements, puzzling everybody, including the initiated. Instead, we are treated to a familiar dramatic situation that allows the writer to explore the evolved relationships of the show’s major characters. They are as we remember them, only changed by time and all that they have endured. They are more resolved to embrace the inevitable than ever — so long as there is room to negotiate.

No performance in the film is more powerful than that of McShane’s as an ailing Swearengen, the unofficial patriarch of Deadwood, who is having difficulty remembering the days of the week and the things he has said. He is losing control of his bodily functions. Swearengen was the series’ most captivating figure, despite his moral repugnance. He was Deadwood’s center of gravity and prime mover — other than the gold that brought people to the Black Hills. But he was also always an acute observer, constantly watching over the camp from his balcony. Time has slowed him down considerably. In the film he favors his role as observer and commentator; Seth Bullock (Timothy Olyphant), now a US Marshall, takes the reins over the dramatic doings. Swearengen orbits the people around him, eyes their challenging circumstances, and provides the insightful, acerbic asides Milch’s writing is celebrated for.

It is tempting to attribute Swearengen’s attitude toward his diminishing condition with Milch’s sobering sense that finishing Deadwood would be impossible. The chance to do it right, completely on his own terms, was lost more than a decade ago. Deadwood: The Movie is inscribed with more self-referential allusions than the series, but Milch also warns us not to read too much into all the suggestions. Swearengen, as he confronts his own mortality, proclaims that he’d “not prolong the chewing up… nor the being spat out.” Initude, he accepts. Rather, he explains, it is the thrashing of the panicked ego he disdains. “It’s the dispatch I find inglorious… The whole delusory fucking self-importance.”

Deadwood’s final installment does not resolve its final conflict. The difficulties of the future remain. Modernity’s march continues unimpeded, while the responsibilities of statehood changes the nature of Deadwood’s relationship to the rest of the country. The character’s attitudes toward one another as they confront the coming transformations are, however, altered by deeper affections and the inevitable demise of Swearengen, who was the most vociferously opposed to any infringement on his own designs — he only adapted when it suited his purpose. There will be no further changes for him. Ironically, Deadwood had already left him behind a decade ago, since the events of the last episode

Deadwood’s conclusion suggests that, as the end comes near, all we can do is try and remember why we are here. And be wise enough to let go once the memories are gone. The opening shots — a train steams toward the light at the end of a tunnel — are a tip off to what kind of bittersweet swan song this is. It is a story filled with what Jane refers to as “loving regret.” The film may not be a wholly satisfying capstone to the series, but Milch’s evocative writing and narrative intelligence do nothing to tarnish Deadwood’s legacy as one of television’s highest artistic achievements.

Lucas Spiro is a writer living outside Boston. He studied Irish literature at Trinity College Dublin and his fiction has appeared in the Watermark. Generally, he despairs. Occasionally, he is joyous.

Watching Deadwood: The Movie what struck me coming back to the show was the argot. I had just been discussing Yogi Berra — if you come to a fork in the road take it, great restaurant but nobody goes there, it’s crowded, etc. — and realized that David Milch, Deadwood‘s auteur, like Yogi, had invented his own. Sometimes it resembles that of Yoda, but with Shakespearian inflections. These Deadwoodians proclaim and perform themselves. Talking softy is not their style. Speeches are, in the mud and amidst the shit, platforms of the Deadwoodian self.