Jazz CD Review: Bill Frisell — “Music IS”

One marvels at Bill Frisell’s improvisations, which can be both surprising and songful.

Bill Frisell: Music IS (Okeh/Sony Masterworks)

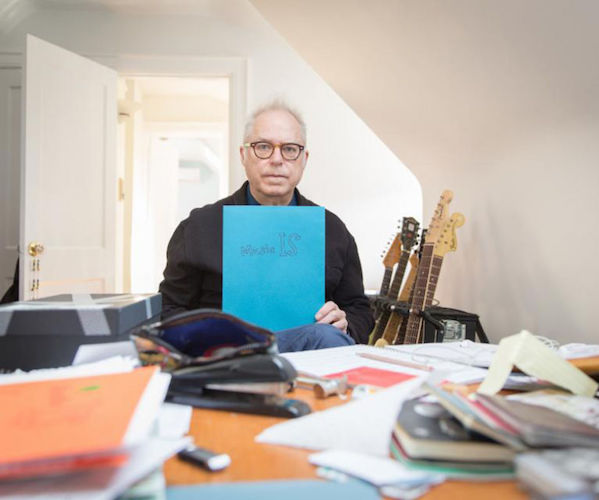

Guitarist Bill Frisell — he seems to splash colors over the music, in waves, as if he were Jackson Pollock pouring paint on a canvas. Photo: Monica Jane Frisell.

By Michael Ullman

In 1982, after having recorded with European bassists Eberhard Weber (Fluid Rustle, ECM) and Arild Andersen (A Molde Concert, ECM), and with drummer Paul Motian (Psalm, ECM) along with Chet Baker, Tony Scott, and Mike Metheny, guitarist Bill Frisell made his own, mostly solo, record, In Line for ECM. Amusingly, the first number of In Line, a dreamy duet with Andersen, is called “Start.” Around this time, in the early ’80s, I heard Frisell perform live with Motian. His approach to guitar was, if not unique, considerably different from the honorable efforts of the army of Wes Montgomery acolytes. He seemed to splash colors over the music, in waves, as if he were Jackson Pollock pouring paint on a canvas. More often than not, his solos began with a resonant chord sustained endlessly. It was if he wanted to create a compelling atmosphere rather than tell a story.

Of course, he could do both. He returned to the solo format in 1999 with Ghost Town. On guitar, banjo, and bass (also drawing on tape loops), he played originals, such as “Creep,” but also the Carter Family’s hit “Wildwood Flower” and Hank Williams’ plaintive “I Am So Lonesome I Could Cry.” A highlight of that album is his cheerful recreation of John McLaughlin’s innocent-sounding “Follow Your Heart,” which he plays cleanly and sweetly. And he makes it swing. By that time Frisell had mastered over-dubbing (and the use of tape loops): when he adds color, and sometimes a bass line, the results never come off as contrived or forced. On “I’m So Lonesome I Could Cry,” he picks out the melody on what sounds like an acoustic guitar — behind him there are resonant, echoing chords. It’s like a bed for the melody to lie on, comfortably. With its varied repertoire, including country (the bête noire of hipsters), Ghost Town amounted to a kind of brave triumph.

Nonetheless, it’s taken 18 years for Frisell to issue another solo record: Music IS. It may be his best yet. Having compared Frisell to Pollock, I was amused to see that he has penned a tribute to a much different painter, “Winslow Homer.” With its eccentric accents and delayed entrances, it’s a blues that could have been composed by T.S. Monk. As Frisell improvises inventively, though without entirely abandoning his original melody, the guitarist gradually adds layers of over-dubbed material. Despite the complication, every line is lucid and the composition moves along joyously. His “Pretty Stars” boasts what sounds like an inevitable melody. But, of course, there’s more to the track than its lyricism.

One marvels at Frisell’s improvisations, which can be both surprising and songful. It never sounds as if he’s straining for effects. His occasional dissonances are as appealing, and as functional, as his most conventionally vocal lines. He can do other things as well, as he reminds us on this new session. In the midst of his songfulness during “Think About It” he plunks down some harsh, metallic sounds. With its grumbling bass line and distorted guitar, the tune’s over before you know it — but it deftly makes its astringent point. The multi-layered “Kentucky Derby” may be meant to suggest the overlapping scenes of the iconic race.

Frisell recreates his tune “Ron Carter” (originally on East-West) and tackles the title cut from Rambler twice. On the original recording, the winsome melody is kept at distance from the listener, mainly through reverb and echo effects. It is also played over a rhythm section that includes tuba player Bob Stewart. The approach is impish: it could pass as a circus band version of the theme song for a Roy Rogers movie. On Music IS, we first hear a seemingly directionless, rapid series of electronic sounds — then Frisell resurrects his country-ish melody. The contrast between foreground and background somehow enhances the appeal of this winsome song. I was happy that there was a second version of Rambler at the end of the album. Frisell is an ambitious colorist who deeply appreciates the charm of simple, suggestive melodies; this ambidextrousness has made him one of the most convincingly lyrical jazz musicians on the scene today.

Michael Ullman studied classical clarinet and was educated at Harvard, the University of Chicago, and the U. of Michigan, from which he received a PhD in English. The author or co-author of two books on jazz, he has written on jazz and classical music for The Atlantic Monthly, The New Republic, High Fidelity, Stereophile, The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Globe, and other venues. His articles on Dickens, Joyce, Kipling, and others have appeared in academic journals. For over 20 years, he has written a bi-monthly jazz column for Fanfare Magazine, for which he also reviews classical music. At Tufts University, he teaches mostly modernist writers in the English Department and jazz and blues history in the Music Department. He plays piano badly.