Jazz Review: Harvey Diamond Quintet at the New School of Music

There was an easy depth to the music, if such is possible, as if the musicians were digging in hard, but with the relaxed assurance that comes of a shared vision.

Harvey Diamond Quintet at the New School of Music, 25 Lowell Street, Cambridge, MA

(l to r) Joe Hunt, Phil Grenadier, George Garzone. Photo: Steve Provizer.

By Steve Provizer

Living in Boston, it’s easy not to notice concerts like this one — 5:30 p.m. on a Sunday afternoon at a music school in Cambridge. There are no billboards or media advertisements plugging the show, just a notice on Facebook and an email. Ho hum. Just another concert featuring five world-class musicians which, if performed in any city other than Boston, New York or Chicago, would be in every jazz fan’s Google calendar.

The lineup, put together by leader-pianist Harvey Diamond included George Garzone, saxophone; Phil Grenadier, trumpet; Jon Dreyer, bass and Joe Hunt, drums. To give you an idea of where these players are coming from: George Garzone is a member of the world-class free improv group the Fringe, a member of the Joe Lovano Nonet and in constant demand for recordings. Grenadier was already gigging as sideman for the likes of Ella Fitzgerald and Mel Torme when he was a teenager. He did duo time with pianist Richie Beirach and has played on more than 50 albums. Dreyer, aside from gigging with scores of jazz musicians, has been a member of the Boston Philharmonic and performed with the Masterworks Chorale. Hunt’s career goes back to the early ’60s and gigs with George Russell and Stan Getz and later on, with Dizzy Gillespie and Kenny Burrell. Diamond is one of the few people around who can boast a decade-long apprenticeship with pianist/teacher Lennie Tristano. His esteem in the jazz community is hard to overstate.

This combination of wide experience and long-term dedication to the music created an atmosphere of, one might say, intense informality. That is to say, the musicians were obviously glad to be in each other’s company and clearly felt relaxed but, at the same time, there was a serious undercurrent and no doubt that everyone was there to blow.

The repertoire Diamond chose to play was standards; tunes the musicians knew inside out. They began with a blues line from Sonny Rollins, “Sunnymoon for Two” in medium-up tempo; a relaxed blues to break the ice. Tenor and trumpet solos both displayed a surfeit of technique as they shaded in and out of bop and post-bop approaches, with Garzone edging more toward the Coltrane end of his tonal range. Diamond was an active accompanist, comping with a force that drove the soloists. His own solo showed a variety of techniques, with some emphasis on locked hands. Time from the rhythm section was dead on.

Next up was a medium tempo “Star Eyes,” a tune that moved solidly into the jazz repertoire after Charlie Parker showed what could be done with it. As in most of the tunes, Diamond started off with a long, out of tempo, intro. On a subtle signal, the tempo solidified and the horns kicked in with the classic background lines until Garzone finally stated the melody. After that, saxophonist put the tune thoroughly through its changes, Grenadier played a fiery solo and I definitely heard the Booker Little influence coming through (after the show, he acknowledged his esteem for Booker). There was a nice melodic bass solo and a series of crisp exchanges with drummer Hunt, until a playful vamp took it home.

The Horace Silver tune “Peace” followed (you may know it as the theme for the WGBH radio show “Eric in the Evening”). Diamond did a long, slow unaccompanied solo-probably too long to be called an “intro.” And, indeed, he took the tune to peaceful, minimalist spaces. Grenadier’s trumpet solo made good use of long tones to continue the atmosphere. A quiet tag ended the song.

A medium-up version of the standard “I Hear a Rhapsody” followed, Garzone taking the A sections of the melody and Grenadier on the bridge. As he did a few times during the night, Diamond laid out for part of the trumpet solo, leaving accompaniment chores to the tasty Hunt and spot-on Dreyer. Sax held the last long tone, while piano and trumpet surrounded it with the right harmony. The visual impression left by watching the group play this tune was of pros sharing a language and digging the conversation.

Next was a ballad-tempo version of Burke & Van Heusen’s “It Could Happen to You.” Diamond again worked a long introductory chorus, playing with substitutions in the melody. Garzone picked up on that idea when his solo began, varying simpler melodic motifs with cascades of 32nd notes. Here, instead of the Coltrane side of his tone, he was more in the neighborhood of a Hank Mobley or Al Cohn sound. Piano comping pushed him hard. Diamond’s solo in tempo was mostly sweetness and light; Dreyer’s solo bass work was especially noteworthy for its good intonation in the thumb position (playing on the higher end of the fretboard). Maybe his classical chops helped out here.

“You Taught My Heart to Sing” was up next and I must admit I’m not especially keen on this tune, written by McCoy Tyner with Sammy Cahn lyrics. The harmony is not that compelling and Diamond approached it very differently than he did the other tunes. It felt to me like more of a set piece, with arpeggios and ostinatos. Very skillfully done, indeed, but not my cup of oolong.

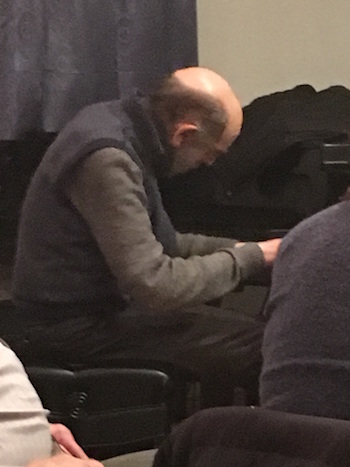

Pianist Harvey Diamond. Photo: Steve Provider.

Then came the Benny Golson tune “Stablemates.” I don’t think Golson ever wrote an uninteresting tune or one that doesn’t inspire soloists and such was the case here. Trumpet and tenor stated the melody and Tenor soloed, playing it pretty much in a bop vein, with few substitutions. Solos had been generally held to one or two choruses during the concert, but Garzone stretched it out, generating more and more steam with each chorus. Trumpet followed, picking up on the energy and then piano, with Diamond showing a lot of strong right hand in his solo. Switches to the Latin sections of the tune were handled flawlessly by Hunt. Throughout, Diamond directed the action from the piano bench, with subtle looks or movements. Smiles all around.

“Body and Soul” followed, with an extended piano intro. Sax then entered, again not stating the melody, but pushing the harmonic implications with simple phrases, repeated motifs, and held notes. Grenadier came in to improvise on the bridge, easily negotiating one of the most famous key changes in jazz. Sax picked up the chorus and piano quietly took it out.

The set officially ended with an up tempo “Tenor Madness,” providing another chance for everyone to enjoy the freedom of playing the blues, drawing on the deep well of approaches they’ve accumulated in the course of long musical lives.

The group came back for an encore of the Thelonius Monk classic “Round Midnight.” It was largely a feature for piano and Diamond approached it in an almost fugue-like way, threading contrapuntal lines through the famous Monk descending bass line. The group closed the tune in a slow walk, with tenor sax re-phrasing the melody and the whole group joining in and then, slowly, fading out.

There was an easy depth to the music, if such is possible, as if the musicians were digging in hard, but were confident they were in touch with each other and that the audience felt that as well. The circle was closed. That’s what communication is about.

This same group, without George Garzone, will be performing next Saturday, March 3, at the New Schoo with singer Sheila Jordan. Sheila is 89 years old but she is no museum piece. Her roots go back to the beginnings of Bop in the 1940’s and her creativity and chops remain completely intact. The deep connections that the musicians displayed in the concert I just reviewed will be brought into a very different dimension by the presence of Ms. Jordan. Heartily recommended.

Steve Provizer is a jazz brass player and vocalist, leads a band called Skylight and plays with the Leap of Faith Orchestra. He has a radio show Thursdays at 5 p.m. on WZBC, 90.3 FM and has been blogging about jazz since 2010.

Tagged: bass, drums, George Garzone, Harvey Diamond, Joe Hunt, Jon Dreyer, Phil Grenadier, saxophone, Steve Provizer