Theater Review: “Call Me Ish” – imaginary beasts’ [or, the whale]

Matthew Woods and his actors do not draw on a faux-naturalist performance style, which is so (unfortunately) fashionable in mainstream theater.

[or, the whale] by Juli Crockett. Directed by Matthew Woods. Presented by imaginary beasts and the Charlestown Working Theater at the Charlestown Working Theater, Charlestown, MA through November 4.

Jaime Semel, Ciera-Sadé Wade, and Sam Terry in scene from the imaginary beasts production of “[or, the whale].” Photo: courtesy of imaginary beasts.

Enter the theater space at the Charlestown Working Theater to see Juli Crockett’s [or, the whale] and one is confronted with Lillian P.H. Kology’s monumental scenic design. At first, the set seems to be an abstract vision of the bleached rib cage of the titular cetacean. But closer inspection reveals it to be the ribs and beams of the shipwrecked Pequod, wrapped in pages from the Dover Thrift Edition of Moby Dick; Or, The Whale by Herman Melville. There is a large swing suspended from the heavens by a rope, sky blue crates of varying sizes, and small globes of clear glass hanging from thin wires, as if the spray of a violent ocean has been frozen in an eternal moment.

Before the production begins, imaginary beasts director Matthew Woods comes on stage to explain that [or, the whale] is not a conventional script. The dialogue is not assigned to specific figures; in fact, there isn’t even a list of speaking characters. Despite the fact that Crockett considers it a play (it premiered in 2001), Woods regards it as the sort of “impossible script” he is most fascinated by.

And Crockett’s script is nothing if not eccentric. While inspired by one of the great American epics, Moby-Dick; or, The Whale, the piece is really a philosophical free-verse poem. (It reminded me of symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé’s nautically themed “A Throw of the Dice Will Never Abolish Chance.”) Forget what your high school English teachers told, that the novel was about the conflict between man and nature. By bracketing the last three words of Melville’s title (often omitted by students and teachers) and turning “or” into a hanging contraction, Crockett draws attention to the fact that her play is not about Ahab’s quest for the whale. Rather, Crockett gives us a quest for Ahab’s lost leg, a quest for wholeness. Is Ahab still Ahab without his leg? Was he Ahab before his leg was lost and he began his mad odyssey? (Crockett’s text often describes Ahab as a “myth” and an “archetype” who is defined by his loss.) Is his leg still Ahab? Do they retain their connection despite their separation? Does the distance between the top of Ahab’s head and the tips of his lost leg’s toes contribute to his height?

Crockett’s abstract concerns don’t necessarily lend themselves to a linear narrative. And this liquidity, reflecting the flux of the ocean and identity, is kept uppermost. Only with the episode of Pip (Ciera-Sadé Wade) the kitchen boy’s rescue after being lost at sea do we get a hint of narrative. Emotional reality is explored through a free-flowing stream of consciousness chorus. Crockett’s script forces the imaginary beasts to create boundaries, to delineate the identities of the characters. Having those baubles frozen eternally in the air turns out to serve as a Parmendian counterpoint to the Heraclitean ever-becoming flux of the play.

Movement coaches Molly Kimmerling and Amy Meyer create an expansive movement vocabulary for the performers; wisely, they never lose sight of the fact that, in the theater, movement, no matter how extraordinary, is not about impressing the audience with pure technique (as is too often the case with nouveau cirque ensembles), but to communicate emotion and ideas.

In the opening movement of the production, Ish (Sam Terry) and She (Raya Malcolm) roll on and off one another by way of a contact-improv inspired invention. It’s not just about creating spectacle – Crockett’s language and Perry and Malcolm’s acting skills generate an emotional impact — one that is perhaps more impressive than the technical displays of nouveau cirque ensembles. Ahab first appears in the form of three persons: Leilani Ricardo, Jaime Semel, and Danny Mourino. (Only Mourino sports his own facial hair; Ricardo’s and Semel’s beards are shredded pages of Melville’s text.) The three Ahabs have bandages tied around their left leg to symbolize the limb lost at sea.

Similarly, at one point, while the ensemble is wearing a large mask (laminated with pages from the Dover Thrift Edition of Melville’s novel), it makes use of an oar, a harpoon, the peg-leg of a chair, and a stovepipe hat to create a fourth puppet Ahab of disparate parts – a marionette that reflects his fragmented identity. As the performers trade parts we begin to wonder: how many parts can be replaced in an old object before it becomes something new?

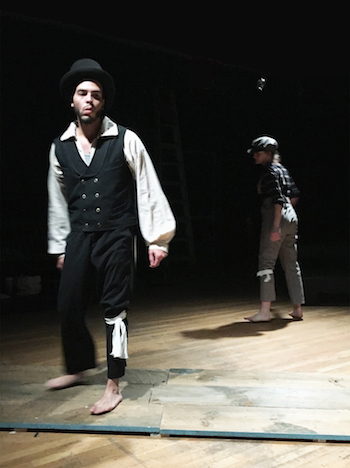

A scene from the imaginary beasts production of “[or, the whale].” Danny Mourino and Jaime Semel in a scene from the imaginary beasts production of “[or, the whale].” Photo: courtesy of imaginary beasts.

There are many such fanciful inventions: puppets representing the ship, sea, and storms; pantomime illusions of hoisting great weight; the appearance and disappearance of actors through panels in the crates.

Woods’s sound design is a complex mixture: sea shanties sung by the ensemble (including a memorable solo song and dance by Wade); the sometimes discordantly swaying chamber-folk music of Kangaroo Rat Music‘s accordion, xylophone, and cajón.

Cotton Talbot-Minkin dresses the performers in period garb (with the exception of Malcolm’s She, whose modern fabrics and skirts of lavender and sky blue scraps are an impressionist allusion to the 19th century). Christopher Bocchiaro’s lighting makes for some memorable visions of shadow and light in the play’s ending scenes — especially in conjunction with the masks.

Obviously, Woods and his actors do not draw on a faux-naturalist performance style, which is so (unfortunately) fashionable in mainstream theater. The results may be strange to those who are more accustomed to television, film, and kitchen sink realism. Nevertheless, the imaginary beasts dive into the piece’s theatrical potential, focusing on what can only be accomplished when actors and audience share risk and a space. Like Ahab, they are on a quest — to serve up the kind of visceral thrill that only live theater can offer.

Ian Thal is a playwright, performer, and theater educator specializing in mime, commedia dell’arte, and puppetry, and has been known to act on Boston area stages from time to time, sometimes with Teatro delle Maschere. He has performed his one-man show, Arlecchino Am Ravenous, in numerous venues in Massachusetts and Rhode Island. One of his as-of-yet unproduced full-length plays was picketed by a Hamas supporter during a staged reading. He is looking for a home for his latest play, The Conversos of Venice, which is a thematic deconstruction of Shakespeare’s The Merchant of Venice. Formerly the community editor at The Jewish Advocate, he blogs irregularly at the unimaginatively entitled The Journals of Ian Thal, and writes the “Nothing But Trouble” column for The Clyde Fitch Report

Tagged: Charlestown Working Theater, imaginary-beasts, Juli Crockett, Matthew Woods, Moby-Dick, Or