Theater Review: “The Whipping Man” — A Secular Haggadah

Flawed and perhaps overwrought, The Whipping Man is worth watching because of the intensity of its individual scenes.

The Whipping Man by Matthew Lopez. Directed by Howard Millman. Staged by Peterborough Players, 55 Hadley Road, Peterborough, NH, through July 2.

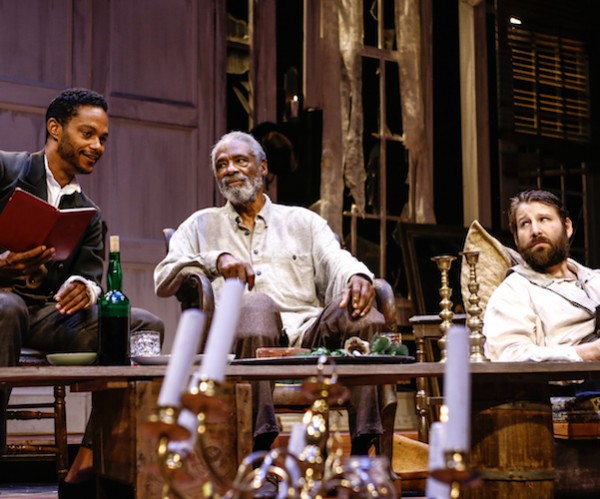

A scene from the Peterborough Players production of “The Whipping Man.” (l to r): Robb Douglas, Taurean Blacque, and Will Howell. Photo: Tyler Richardson.

By Jim Kates

It is a dark and stormy night, April 13, 1865.

Into a half-burned, looted grand house in Richmond, Virginia stumbles a wounded Confederate soldier. He collapses on the floor. Caleb De Leon has come home from war. He is discovered and then succored by Simon, who has remained in Richmond to wait for the return of his own wife and child. They have gone off somewhere, as Simon understands it, with their former master, Caleb’s father, but will return soon.

The help Simon provides Caleb includes surgery (he amputates the soldier’s right leg). For the remainder of The Whipping Man, Martin Lopez’s problem play, Caleb remains immobilized on a sofa. Simon’s ministrations are assisted by an ample flow of whiskey, procured from abandoned neighboring houses by John, another new freedman, formerly a slave in the De Leon household and Caleb’s childhood companion.

Caleb makes a remarkable recovery. Within fewer than twenty-four hours, he manages to survive a gangrenous fever; he is coherent and actively engaged with both Simon and John, who are at odds with each other, not so much about what to do with their new freedom as what to get out of the old household. Caleb’s father has promised Simon money in order to establish a new life; John has his own less dignified plans.

The Whipping Man is fraught with real life improbabilities, dramatic possibilities, and portentous irrelevancies. Each character guards a secret from the others. Don’t expect Lopez’s script to adhere to the conventions of realistic fiction; instead, we get the frame-by-frame anecdotal movement of a comic book or an allegory. Each plot segment carries its own tensions and confrontations, one intriguing but contrived situation succeeding another.

The irrelevancies engage us in the story and only in retrospect do they come off as gimmicks. It makes no difference to character or plot that Caleb apparently has come home without an official dismissal from the Confederate army, although this is supposed to convey that he is somehow legally at risk.

And it also makes surprisingly little difference that the De Leon family is Jewish, although this circumstance provides the atmosphere and the vocabulary of the plot. We are supposed to believe that some liberal values go along automatically with the Judaism of the household — John has been taught to read, for instance, in defiance of state laws — and the second act builds to an ironic seder in the shadow of Lincoln’s assassination. But nothing significant to the psychology or the narrative occurs in the De Leon house that could not also have taken place in a Presbyterian household.

Howard Millman’s direction takes each scene as it comes with an integrity that acknowledges its dramatic weight, but he can’t overcome the narrative disjunction as one contrivance piles up on another. Nevertheless, he deserves a great deal of the credit for keeping the problems and tensions interesting throughout the The Whipping Man as it chugs on.

Taurean Blacque conveys Simon’s skill, dignity, and ultimate outrage. He becomes especially eloquent during the character’s set-pieces, which express the sentiments of Jewish wisdom and practice. War is not evidence of God’s absence but of man’s dereliction from God, he reassures the disillusioned Caleb. Judaism is all about posing questions; it is a Biblical role, the old, wise, illiterate patriarch. Think Eliezer, Abraham’s major-domo. At the end, his own humanity sends him fleeing into the dark.

Robb Douglas is always in restless movement as John, taking long, stalking strides across the stage, back and forth, flirting at first with suggesting the trickster stereotype. But the performer settles into a stability that appears to be at odds with his actions. Although John drinks constantly throughout the play — Simon refers to his inebriation — Douglas displays little incoherence or disability. He is relentlessly efficient, keeping the household in motion. As the only character in the play who actually learns and grows, the figure’s motion is appropriate. We wonder what will become of him after he shares Passover wine with Caleb, a final revelation without a clear resolution.

Will Howell faces the problem that Caleb is the least well developed of the three characters, functioning more as a prop for the other two to bounce off, unable to move either physically or psychologically once the plot is underway. His most expressive moments come when he registers physical pain. Still, Howell makes us understand and feel Caleb’s initial naïvete and then his anguished humanity.

Flawed and perhaps overwrought, The Whipping Man is worth watching because of the intensity of its individual scenes. It is one more retelling of the legacies of slavery and the burdens of liberation, this time as a secular haggadah.

Jim Kates is a poet, feature journalist and reviewer, literary translator and the president and co-director of Zephyr Press, a non-profit press that focuses on contemporary works in translation from Russia, Eastern Europe, and Asia. His latest book is Muddy River (Carcanet), a translation of verse by Russian existentialist Sergey Stratanovsky. His translation of Mikhail Yeryomin: Selected Poems 1957-2009 (White Pine Press) won the second Cliff Becker Prize in Translation.