Music Commentary: Thoughts on the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s 2017-18 Season

On paper, at least, the upcoming season of the BSO is a bit of a letdown: cautious, unthreatening, comfortable.

Andris Nelson leading the Boston Symphony Orchestra. Photo: Winslow Townson.

By Jonathan Blumhofer

The more things change, the more they stay the same. That old adage seems to me a pretty good epitaph for the Boston Symphony Orchestra’s (BSO) 2017-18 season, the fourth of the Andris Nelsons era, which was announced rather quietly on March 31st. On paper, at least, it’s a bit of a letdown: cautious, unthreatening, comfortable.

To be sure, the news isn’t all bad. Nelsons’ Shostakovich series continues with the Fourth, Eleventh, and Fourteenth Symphonies. Charles Dutoit conducts The Damnation of Faust. Some welcome rarities – from Étienne Méhul’s The Amazons Overture to a pair of Schumann lieder for chorus and orchestra to György Ligeti’s Violin Concerto – turn up. Thomas Adès’ term as artist-in-association continues apace. Jonas Kaufman sings the title role in Act II of Tristan und Isolde. Some distinguished guests absent for several years (e.g. Alan Gilbert and Leila Josefowicz) make welcome returns. Jean-Yves Thibaudet joins the orchestra as its first artist-in-residence. And the BSO takes its first tour (with Nelsons) to Japan in November.

But on the whole, the season reads like an opportunity missed. Its principal flaw is that it’s familiar and safe: it almost entirely avoids taking any sort of artistic risks. On top of that, when the opportunities to do something really striking come up, the BSO responds with half-measures.

Take, for instance, the orchestra’s “Leonard Bernstein Centennial Season Celebration.” On the surface, it’s an immensely welcome survey given Bernstein’s long (if occasionally contentious) history with the BSO and his often-overlooked significance as a composer. What does this consist of? Well, it kicks off in September with fluff. There are the evergreen Symphonic Dances from West Side Story, some TBA vocal selections, and the Divertimento. Mixed among those choices is an actual weighty piece, Halil, Bernstein’s darkly lyrical nocturne for solo flute.

OK, OK, you’re probably thinking, it’s Opening Night: the program needs to be friendly and well-known and, besides, the BSO has only played the Divertimento all (or in part) just four times since premiering it back in 1980. This, and a very rare hearing of Halil, is just the sort of thing you ought to be celebrating. And I agree with that sentiment: both the Divertimento and Halil are wonderful pieces, fully deserving of frequent hearings. I’ve known and loved them both for more than twenty years.

Perhaps my frustration with that program would be mitigated if the rest of the orchestra’s Bernstein “Celebration” covered more ground. But it doesn’t. Instead of Fancy Free (which the BSO’s never played in full) or Facsimile (not heard since 1987) or Songfest (again, never played in full) or the Concerto for Orchestra (never played at all), we get The Age of Anxiety and Kaddish Symphonies. Granted, neither are insignificant and both haven’t been performed at Symphony Hall for a while. And there’s a rabble-rousing element to Kaddish (though that’s largely done in by Bernstein’s cliché-ridden, ham-fisted narration for it).

But that’s all there is. Taken in total, this is partial and superficial programming; almost like it was an afterthought. Bernstein’s most significant and controversial works – Mass and A Quiet Place – are no where to be found. Yet, for any true celebration of Bernstein’s life and work, they ought to be a part of it. So should the aforementioned ballets and late masterpieces like Dybbuk and Arias and Barcarolles. The theater works – On the Town, Wonderful Town, Trouble in Tahiti, and A White House Cantata, even more than West Side Story – deserve their own full focus, not just excerpts on a single night. And Songfest, that great, un-heralded national anthem that we need to hear now more than ever, ought to be sung and played widely: in Boston, at Tanglewood, on tour in Tokyo.

The fact is, the BSO could have devoted the entire season to presenting a nuanced, engrossing portrait of one of this country’s greatest and most-engaged musical citizens. It mightn’t all have been pretty (Bernstein was a complicated and contradictory man, after all), but it would surely have been timely, not to mention intellectually stimulating and creatively engaging. In the event, he gets passing notice from his home-town orchestra – a far cry from how the San Francisco Symphony and Los Angeles Philharmonic (ensembles which boast far slimmer personal connections to Bernstein than the BSO does, it should be pointed out) are approaching the same anniversary.

Of course, maybe the BSO will pull off something worthy of the man: Bernstein’s 100th birthday doesn’t fall until August 2018, so the 2018-19 season might fulfill the incomplete promise of this one. But, given the orchestra’s current heavy focus on Strauss, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms, Dvorak, et al., I’m not about to hold my breath.

At least the Bernstein celebration is a festival, of sorts. Few discernable threads tie together much of the rest of the season and the ones that do aren’t always inspiring. The “Leipzig in Boston” week, the first installment in a several-years-long exchange between the BSO and Nelsons’ Gewandhausorchester, is, what, exactly? More helpings of Bach, Mendelssohn, and Schumann? Apologies if that’s something about which it’s difficult to get genuinely excited.

Of course, it’s not a requirement that orchestras be constantly churning out monthly (or yearly) themed concerts. Still, if you’re going to play so much of the same repertoire year-in and year-out, the benefits of such schemes – to provide revealing context and contrast, among other things – become pretty quickly apparent.

And some topical series would have been an asset for the BSO’s 2017-18 season, which has the added distinction of repeating a good number of pieces heard at least once over the preceding five. Thus Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, which Anne-Sophie Mutter brings to Boston this month, reappears in October, now with Gil Shaham as the soloist. Brahms’s Piano Concerto no. 2, heard last November, returns next spring. Other pieces being repeated on an annual (or near-annual) basis include Beethoven’s Piano Concertos nos. 1 (last heard in 2016), 3 (2015), and 4 (also 2016), as well as his Symphony no. 8 (2014); Brahms’s Violin Concerto (2015); Bruckner’s Symphony no. 4 (2013); Dvorak’s Symphony no. 7 (2012); Mahler’s Symphony no. 1 (2016); Mozart’s Gran Partita Serenade (2014), plus his Fortieth and Jupiter Symphonies (both last played in 2015); Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto no. 2 (2015) and Symphony no. 5 (2012); Ravel’s complete Daphnis et Chloe (2014); Schumann’s Spring Symphony (2015); Strauss’s Don Quixote (2015); Tchaikovsky’s Pathetique Symphony (2014); and Wagner’s Siegfried-Idyll (2013).

That’s certainly not the whole season – but it represents major pieces across a good portion of it. And it begs the question, is there really nothing else out there to play? Surely that’s not the case.

What’s more, the orchestra’s upcoming survey of new music is, even by its own standards, depressingly thin. With the exception of the local premiere of John Adams’s Sheherezade.2 and a new piece by Jörg Widmann, there’s very little of substance (read: much more than 10-minutes duration) to be found. Yes, there’s a score by Arlene Sierra (the season’s token female composer), a commission from Sean Shepherd, our welcome annual serving of Adès, and the BSO finally plays something by Derek Bermel at Symphony Hall. But that’s it. Six living composers (this season, by contrast, presents music by nine) represented by barely of two hours of music (vs. closer to four this year). Swap out The Damnation of Faust or Mahler 3 and you could pack it all into one subscription series that’s on and gone in the blink of an eye.

Again, this begs questions, the first of which is, is there really nothing else out there to play? Of course we know that’s not the case, especially for these composers. Bermel’s Elixir, for instance, is a lovely curtain-raiser. But why can’t we get something more substantial of his, like Canzonas Americanas or Voices or Thracian Echoes? Or maybe all three: it’s not like Bermel’s music isn’t rigorously well-written but also audience-friendly. No offence to Leonidas Kavakos, but do we seriously need to hear Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto no. 2 again (after it turned up on no less than four different programs in and around Boston just three seasons back)? Really? The same case could be made for each of the other composers fortunate enough to get any air time, not to mention myriad others shunted aside to make way for more servings of Strauss, Mozart, Brahms, Mahler, Stravinsky, Tchaikovsky, and Beethoven.

The even more fundamental follow-up question is, does the BSO even care that it’s the steward of a living, breathing, diverse, living tradition of contemporary music? You don’t get the sense that they do here. Recent seasons may not have gone overboard with new music, but they surely haven’t been as sorely wanting as next year promises to be. One hopes this isn’t a sign of things to come.

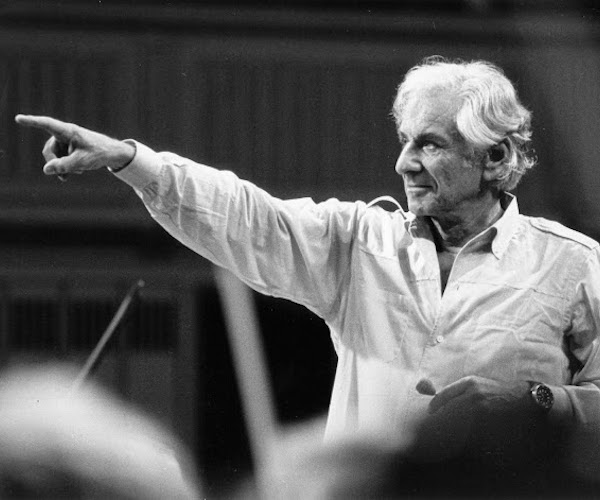

Leonard Bernstein conducting. The BSO would do well to heed his call: artists should play a role in calling out and helping find solutions to society’s abuses, injustices, and great dilemmas. Photo: Operalia.

Now, I fully appreciate the fact that the BSO is in the business of selling tickets and drawing an audience. I’m well aware that familiar names and pieces are a surer box-office draw than obscure works by Amy Beach and Jonathan Harvey or Christopher Rouse. I know there’s a delicate balance to be struck between pleasing donors and corporate sponsors and taking artistic initiative. And I’ll concede that many who attend BSO concerts likely do so to experience some sort of emotional and/or spiritual comfort from familiar works away from the madness of the outside world.

But the BSO has a number of things going for it that should encourage it to break out of such an artistically-crippling mindset. For one, its financial health is extremely good. It also boasts a charismatic, popular music director whose recent forays into new music and off-the-traditionally-beaten-path repertoire have been intensely rewarding. And it’s got a significant audience of young professionals and intellectuals curious about the new and primed for artistic daring (and, in my experience, there are more than a few older professionals and -intellectually-engaged folks fired up by the same). Moreover, we constantly live in times that call for artistic leadership. In certain periods the summons is louder than others; now is one of those: if the Age of Trump isn’t a time for artists and arts institutions to take principled, forceful stands, when is?

It may have sometimes come off a bit pie-in-the-sky, but next season’s birthday boy had more than a few thoughts on this very matter. Most of Bernstein’s output tackles the nitty-gritty of contemporary life and, in his day, he was more than happy to speak out on any and all subjects under the sun that concerned him. And why wouldn’t he? In Bernstein’s worldview, artists played a key role in calling out and helping find solutions to society’s abuses, injustices, and great dilemmas. “It’s the artists of the world, the feelers and thinkers,” he told students at the Berkshire Music Center in an address in 1970, “who will ultimately save us; who can articulate, educate, defy, insist, sing, and shout about the big dreams.”

Granted, that might be a bit idealistic (and Bernstein was nothing if not an idealist). Even so, his was a call to artistic boldness, not timidity or ambivalence. Indeed, in another address, at John’s Hopkins University a decade later, he offered up dual observations that are especially pertinent today: that, “[t]o search for truth, one must be drunk with imagination” and that “[m]ind-boggling time is the perfect moment for fantasy to take over; it’s the only way to resolve a stalemate.” Would that the BSO’s 2017-18 season, if it wouldn’t showcase more of Lenny’s music, at least exhibited more of his questing, provocative spirit.

Jonathan Blumhofer is a composer and violist who has been active in the greater Boston area since 2004. His music has received numerous awards and been performed by various ensembles, including the American Composers Orchestra, Kiev Philharmonic, Camerata Chicago, Xanthos Ensemble, and Juventas New Music Group. Since receiving his doctorate from Boston University in 2010, Jon has taught at Clark University, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, and online for the University of Phoenix, in addition to writing music criticism for the Worcester Telegram & Gazette.