Book Review: “The Teeth of the Comb” — Brusque Tales of Rebellion

These tales have an incendiary energy, but Osama Alomar handles his narrative explosives with restraint, wisdom, care, and precision.

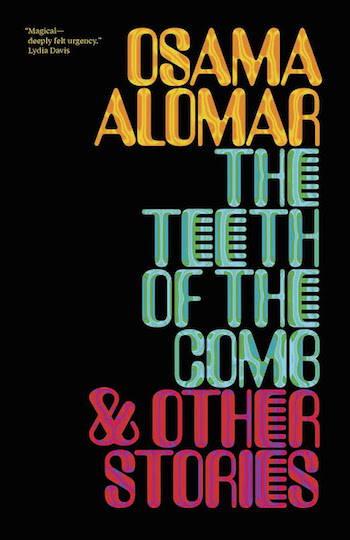

The Teeth of the Comb & Other Stories by Osama Alomar. New Directions, 96 pages, $13.95 (paperback).

By Lucas Spiro

Osama Alomar writes with a kind of explosive but moderated rage. And who can blame him? Born in Damascus, living in exile since 1998, Alomar is now a citizen of the United States. But he is keenly aware of his homeland, and how horribly the lives of those he left behind have been decimated by a brutal war. Syria’s anguish and violence permeates Alomar’s new collection The Teeth of the Comb & Other Stories. These tales have an incendiary energy, but Alomar handles his narrative explosives with restraint, wisdom, care, and precision. His anger is filtered through an adroit use of distance; The Teeth of the Comb makes use of personification, biting allegories, and tightly wound parables to make their moral points, arrived at in the space between humanity’s lofty ideals and demoralizing cynicism.

Western politics have made concepts of good and evil problematic: conservative dogma runs up against liberal relativity. The election of Trump, ushering in the “post truth age,” has accelerated this ethical confusion. But truth has never been more important if we are to cut through the current paralysis and act with justice to those who deserve it. Alomar’s stories are dedicated to inspiring correct moral action, calling on patience and anger to overcome complacency. The combatants in his moral battles are ambiguous, but their victims are not. The poor, the sick, the cold, the marginal, are condemned to suffer the self-serving befuddlement of the powerful.

In the Arab world, Alomar is a highly regarded writer of fiction and poetry. (In the U.S. he has made a living as the driver of Car 45 for a Chicago taxi cab company.) He specializes in the al-qisa al-qisara jiddan (“the very short story”), a rich tradition that goes back at least as far as One Thousand and One Nights. The best known practitioner of the form — and Alomar’s biggest influence — is Kahlil Gibran. Alomar kept a copy of Gibran’s work in the passenger seat of Car 45 along with a notebook, where he jotted down his stories and prose poems in between fares. The very short story combines elements of folk tale, fable, allegory, parable, religion, and philosophy; the genre’s brusqueness illuminates the dark, internal conflicts of what it means to be human. Alomar’s tales inevitably take a political bent, dramatizing the crises of the global poor via the experiences of every kind of life — and object.

In the world Alomar creates, wolves, snakes, daggers, rocks, waste, the stars, and the elements all act and think. Things such as watches and combs are given life; they think and hope, entertain beliefs and then have them crushed. Nothing that has ever come into existence is too small to command Alomar’s attention. No object is too minuscule to escape making a rebellious point. Here is the title story:

Some of the teeth of the comb were envious of the class differences that exist between humans. They strived desperately to increase their height, and, when they succeeded, began to look with disdain on their colleagues below.

After a little while the comb’s owner felt a desire to comb his hair. But when he found the comb in this state he threw it in the garbage.

Would it be possible to find a more novel justification for “workers of the world unite”?

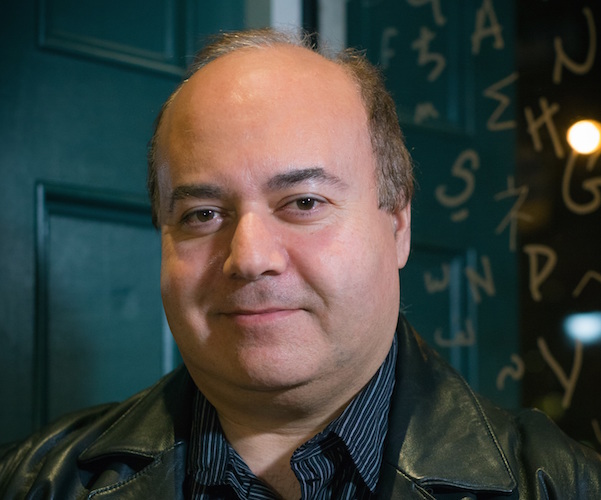

Author Osama Alomar. Photo: City of Asylum

One of Alomar’s targets is free market capitalism, particularly the devastating ways in which it has generated global poverty. In “Get on Before Me?” people from the first world and the third world are standing on a train platform. People from the third world are boarding trains to the past, while the first world passengers board trains to the future. Two men from the third world attempt to get on the train bound for the future, but they argue about which one should get on first. The ‘third worlders” miss their opportunity and the train speeds off. A violent fight breaks out for a spot on the train headed toward the past. In “On Top of the Pyramid,” an animated garbage bag climbs the “social pyramid shimmering in sunlight.” Once it reaches the top, the bag is pierced by the tip of the pyramid: “Soiled water mixed with garbage poured down the four sides until the whole structure was covered in a monstrous pile of refuse.” When waste rules, all becomes tainted, complicit in the general decay.

Alomar makes ample use of Middle Eastern traditions in his work. But, given its focus on hunger around the world, his stories are very much addressed to an international readership. His pieces not only draw on Gibran, but on Franz Kafka’s absurdity, Karl Marx’s theory of commodity fetishism, Ernest Hemingway’s brevity, and William Blake’s lyrical anarchism. In terms of the latter, The Teeth of the Comb features a number of re-imaginings of the devilish aphorisms in the Songs of Innocence and of Experience. Many of the volume’s parables would be apt entries in the “Proverbs of Hell.” In one story, Alomar writes that he is “convinced that humans must be the result of a marriage between heaven and hell.” The dialectical clash between good and evil, hope and despair, takes place in all of us. For Alomar, the crime is that this paradoxical give-and-take is contingent on the destruction of others, usually those who are lower on the food chain.

Not every story/parable in the collection is effective. Alomar’s fables can be heavy handed; his didacticism is an outgrowth of his desire to spur readers to action. Also, keep in mind that he wrote most of The Teeth of the Comb in between trips to and from O’Hare airport. Is it surprising that his tales would reflect his frustration with his day job? (Recently, Alomar has been granted a residency through the City of Asylum project in Pittsburgh, where he will be given the time and freedom he needs to practice his craft.) Judging by the stories in this superb collection, he deserves to enjoy the respect and success here he had in Syria.

Lucas Spiro is a writer living outside Boston. He studied Irish literature at Trinity College Dublin and his fiction has appeared in the Watermark. Generally, he despairs. Occassionally, he is joyous.

Tagged: Lucas Spiro, New-Directions, Osama Alomar, short stories, Syrian

I wonder how many people heading to the airport knew they were getting rides from a highly regarded writer of fiction and poetry. Superb review, Alomar sounds like an important voice on a pressing subject, and with an interesting combination of literary influences all mixed in. A great, timely piece!