Music Commentary Series: Jazz and the Piano Concerto — Mavericks, 1923-1955

This post is part of a multi-part Arts Fuse series examining the traditions and realities of classical piano concertos influenced by jazz. The articles are bookended by Boston Symphony Orchestra concerts: the first features one of the first classical pieces directly influenced by jazz, Darius Milhaud’s Creation of the World (February 19 – 21); the second has pianist Jean-Yves Thibaudet performing one of the core works in this repertoire, Maurice Ravel’s Concerto in G (April 23 – 28). Steve Elman’s chronology of jazz-influenced piano concertos (JIPCs) can be found here. His essays on this topic are posted on his author page. Elman welcomes your comments and suggestions at steveelman@artsfuse.org.

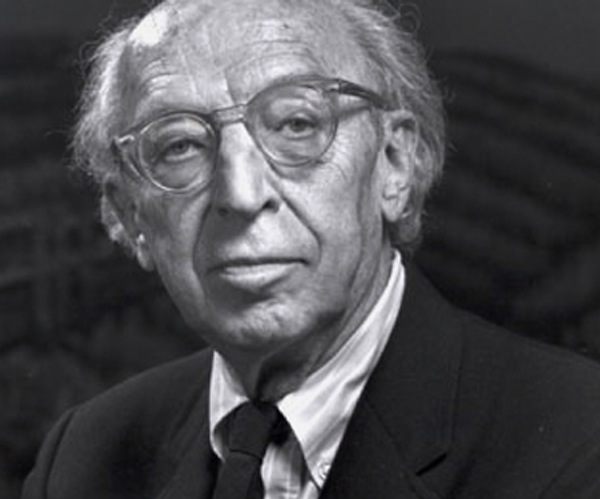

Erwin Schulhoff — the first classical composer to use “jazz” in a score.

By Steve Elman

So far in this survey, I’ve pointed to two main streams that influenced the use of jazz in piano concertos – one from 1920s New York and one from 1920s Paris. George Gershwin’s Concerto in F is the landmark work of the first stream; Maurice Ravel’s Concerto in G is the landmark work of the second.

But some of the most interesting piano concertos influenced by jazz have been written by composers who were blazing their own paths, people who weren’t committed to a particular school or way of thought – in a word, mavericks. They could not fail to be touched by the works that preceded them – especially by Gershwin’s – but for the most part, what they brought to the JIPC is their own ingenuity, and when they used jazz, they used it in distinctive ways.

Here’s the first part of a catalog of the best of the maverick works. The works in this post and the next two provide some of the most rewarding listening I’ve had. Each one of them gave me the chance to explore a perspective on music significantly different from my own. Even the ones that fail to reach their goals are instructive because of their ambitions. My only caveats to the first-time listener are the ones I learned to give to myself: come to each one with your ears open, expect the unexpected, and give each composition the benefit of the doubt. My short notes will never convey the full impact of these pieces. For that, you must listen.

This first group of mavericks all have their roots in the 1920s, but they demonstrate that Gershwin’s way wasn’t the only way.

Erwin Schulhoff’s Concerto [No. 2] for Piano and Small Orchestra, Op. 43 (1923) is the first classical piece to use the word “jazz” in a movement marking (with the possible exception of Schulhoff’s own Études de jazz [Jazz Etudes], some of which were supposedly composed in the 1910s). It’s also the first of the maverick JIPCs, a landmark work in this survey, and great music, whether or not you care about jazz. I can almost guarantee that it will provide a first-time listener who is even marginally receptive to new sounds with a remarkable and worthwhile experience. The composer, born in Prague, was a Dadaist and a leftist, and much of his music reflects his artistic and political point of view. He began composing jazz-influenced piano pieces almost as soon as jazz took hold in Europe and by the time he wrote his Suite for Chamber Orchestra in 1921 he was dancing the night away in Prague to little nightclub bands. You can hear Schulhoff himself playing piano in some 1928 recordings that display his sophisticated knowledge of early jazz, and how well he could swing. Excerpts from his Études de jazz, Esquisses de jazz, and Rag-Partita have been reissued on London / Decca CD, and they’re hearable for free via Spotify.

If you like your twenties cabaret music with a Kurt Weill flavor, you’ll hear it in Schulhoff. If you like thumb-your-nose-at-authority brashness, you’ll get it in Schulhoff. If you like Bernard Herrmann’s music for Vertigo, you’ll hear it — eerily prefigured, 20 years earlier — in Schulhoff. If you deplore artistic worth cut short by the Nazis’ anti-Semitism, you can reflect on that crime against humanity while listening to Schulhoff. His concerto defies easy summary, but in it you’ll hear the Vertigo ostinato, a parody of Berlioz’s “march to the gallows,” a gypsyish mini-sonata for piano and violin, show-band percussion effects, a great trumpet solo, a siren, and plenty of virtuoso exercises for the piano player.

Aaron Copland: he put jazz into a piano concerto long before he wrote “Appalachian Spring.”

Schulhoff’s youthful bad-boy persona was disciplined by a certain amount of middle-European restraint. The American composer George Antheil embraced the identity of an iconoclast as only an American could. His piano concertos come from a period when he was no longer interested in jazz, but his Jazz Symphony for Piano and Orchestra (1925 – 1927) has to be included, at least in an honorary way, in this roster of maverick JIPCs. It’s a serious burlesque in one movement, in some ways serving up a scoffing reply to Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” (1924). The jazz elements include the use of saxophones and banjo, a second theme based on the second strain of Zez Confrey’s “Kitten on the Keys” (1921), and a prominent growl trumpet solo over tramping rhythm, much like Bubber Miley’s work in Duke Ellington’s early band. But there’s much more: some obsessive repetition that Antheil referred to as “mechanical” music, outrageous piano clusters, orchestral crashes, and a completely unexpected conclusion with a sweet waltz theme, derived (I think) from a popular song of the time, “Standing on the Corner, Didn’t Mean No Harm,” subtitled “Oh! My Baby,” written in 1924 by George “Honey Boy” Evans, the composer of “In the Good Old Summertime.” If you have a sense of humor, Antheil’s Jazz Symphony should make you laugh out loud.

There’s American humor of a different kind in Aaron Copland’s Concerto for Piano and Orchestra (1926). Only the short-sightedness of the programmers of symphony orchestras has prevented this work from taking its rightful place as the third masterpiece of twenties JIPC, alongside Ravel’s and Gershwin’s. That reluctance can partly be explained because this work will probably puzzle classical audiences who are expecting Appalachian Spring or Rodeo. It’s from the composer’s early experimental years, for one thing, and it’s gently ironic, for another. The form is unconventional; there is no slow movement. Jazz accents abound. In the first movement, there is a notable bluesy shading, led by the clarinet, edging toward Gershwin, and there is a near-quote from one of the Gershwin piano preludes (which were written the same year as this concerto). The piano part in that movement features a short cadenza with a twenties jazz feel and the most Monkish chords ever in a classical concerto (Thelonious was only 9 years old at the time). In the second movement, interjections from muted trumpet, alto saxophone and clarinet are very jazzy, and the piano part strongly evokes Harlem, with James P. Johnson and Ellington just beneath the surface. It’s worth noting that when the piece was recorded with Copland at the piano in 1962, he gave the piano part a jazzier flavor than other interpreters have, so that recording is much preferred. One more note for New Englanders: the piece had its first performance in 1927, at Symphony Hall, played by the Boston Symphony Orchestra, led by Serge Koussevitzky, with Copland as piano soloist.

The life of Erwin Schulhoff came to an end at the Nazi Würzburg concentration camp in Bavaria in 1942. A year later, another musical maverick, Dutch composer Leo [Leopold] Smit, died at the Sobibor camp in occupied Poland. Like Schulhoff, Smit wrote a JIPC, but the two pieces have nothing in common. Smit’s Concerto for Piano and Wind Orchestra (1937) is undoubtedly influenced by Stravinsky’s Concerto for Piano & Wind Instruments (1923 – 24), but it’s more honestly jazzy. The piece makes perfect sense as a kind of update of Stravinsky, if you consider the fact that in the nine years between the two pieces jazz had taken a giant step into the swing era and Gershwin had become music that everyone knew. Smit’s humor comes to the fore in the final movement. A series of chords introduces the unmistakable expectation of a classical-era finish, but the piano takes over in an Impressionist vein and the winds gradually come in behind, leading to the kind of snappy conclusion that Stravinsky tacked on to his concerto. One more note: this Leo Smit should not be confused with American pianist-composer Leo Smit (1921 – 1999), who was a great exponent of Aaron Copland’s work.

George Gershwin, Dana Suesse, and Paul Whiteman.

Until South African composer Nadia Charmaine Burgess undertook a jazz piano concerto last year, the only woman I know of who ventured into the JIPC is Dana Suesse (1909 – 1987). She more than pulls her weight, with three piano concertos that show varying degrees of jazz influence, one of which is a milestone. In 1932, Paul Whiteman commissioned her Concerto in Three Rhythms [for Piano and Orchestra] for his fourth “Experiment in Modern Music” concert. Whiteman specifically requested something like Rhapsody in Blue, which he had commissioned for the first concert in the series, and Suesse obliged so convincingly that the piece earned her the nickname of “the girl Gershwin,” which unfortunately stuck to her throughout the rest of her life. The concerto, orchestrated with Ferde Grofé, follows in Gershwin’s footsteps at first, but then goes its own way. The first movement, which has two slow themes very reminiscent of Rhapsody in Blue, may even be something of a parody. Considering that the rest of the piece is much less derivative, this mimicking approach may be a sly “You-want-Gershwin?-I’ll-give-you-Gershwin” fillip. The second movement is entitled “Blues,” and it suggests that Suesse knew something of Duke Ellington, especially in the opening piano part and a woodwind passage later on. The last movement has some ragtime and notable dance-band effects, including call-and-response.

In 1941, Suesse returned to the form, but left out the jazz in her Concerto for Two Pianos and Orchestra. This is a thoroughly late-Romantic concerto, evoking Rachmaninoff, especially in the big themes and orchestral swells, along with Beethoven, especially in the last movement.

Much more interesting from this survey’s point of view are the two concertos she wrote in 1955. Her Concerto Romantico for Piano and Orchestra comes out from under Gershwin’s shadow without leaving him behind completely. it probably ought to be taken at face value, as another “Romantic” concerto, although Suesse adds a good deal of post-Romantic dissonance and shows her sensitivity to jazz.

The second piece from 1955 steps into new and different territory, and qualifies Suesse for true maverick status. Her Jazz Concerto in D Major for Combo [Piano, String Bass and Traps] and Orchestra aka Concerto in Rhythm is the first piano concerto I know of by a classical composer that makes use of the traditional jazz rhythm section of bass and drums. The rhythm section is not particularly prominent until the last movement, so there are many moments that feel like a traditional piano concerto. The work is a kind of colloid, where the contrasting sources of classical music and jazz maintain their individual identities. At one moment, late-Romantic passages for piano and orchestra suggest Rachmaninoff albeit with more modern harmony. At others, the music is strongly jazz-inflected, with bass and traps mostly providing subtle underpinning. The first movement’s cadenza, without bass or traps, is adventurous harmonically without losing the basic key: it almost slips into boogie-woogie at one point. The last movement is in tempo throughout, except for a pealing-bells section at the center, with traps given a much bigger role. The conclusion of the movement feels more attuned to a Broadway theater than a concert hall.

Unfortunately, the only recording of this piece to date feels under-rehearsed. It is technically flawed as well, with bad balance and considerable room noise (including the sound of score pages being turned). If only for proper critical assessment, this work deserves a serious and scholarly reexamination and a well-rehearsed performance.

More: To help you explore compositions mentioned above as easily as possible, my full chronology of JIPCs contains detailed information on recordings of these works, including CDs, Spotify access, and YouTube links.

Next in the Jazz and Piano Concerto Series — Mavericks, 1938-1983

Steve Elman’s four decades (and counting) in New England public radio have included ten years as a jazz host in the 1970s, five years as a classical host in the 1980s, a short stint as senior producer of an arts magazine, thirteen years as assistant general manager of WBUR, and currently, on-call status as fill-in classical host on 99.5 WCRB since 2011. He was jazz and popular music editor of The Schwann Record and Tape Guides from 1973 to 1978 and wrote free-lance music and travel pieces for The Boston Globe and The Boston Phoenix from 1988 through 1991.

He is the co-author of Burning Up the Air (Commonwealth Editions, 2008), which chronicles the first fifty years of talk radio through the life of talk-show pioneer Jerry Williams. He is a former member of the board of directors of the Massachusetts Broadcasters Hall of Fame.

Tagged: Aaron-Copland, Dana Suesse, Erwin Schulhoff, George Gershwin, JIPC