Book Review: “Mr. and Mrs. Disraeli, A Strange Romance” — But an Amazing Marriage

Daisy Hay turns her sharp yet sympathetic eye on Mary Anne and Benjamin Disraeli, whose marriage seemed unlikely at the start but which grew into something not only strange but, even in modern terms, amazing.

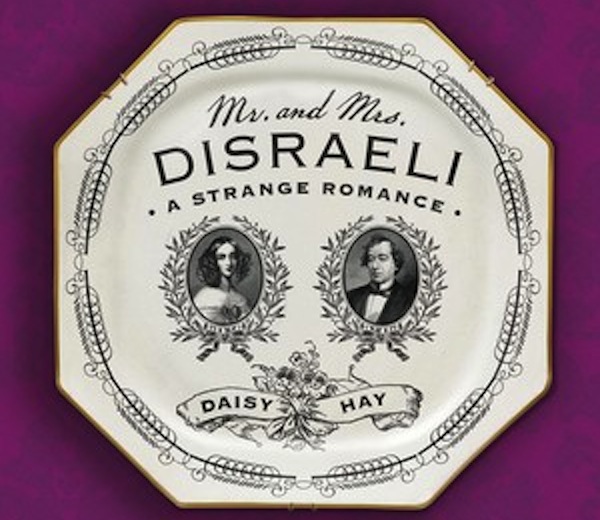

Mr. and Mrs. Disraeli, A Strange Romance by Daisy Hay. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 308 pages, $27.

By Roberta Silman

Daisy Hay is a wonderful young English writer whose curiosity and determination led her to an untouched trove of Mary Anne Disraeli’s letters. Add to that her ability to weave many historical facts and characters into the background fabric of her story and a style uncannily reminiscent of Jane Austen’s, and you have some idea of the rare pleasures in store for you when you pick up this new biography. Previously Hay had immersed herself in the English Romantic poets (The Young Romantics), now she turns her sharp yet sympathetic eye on Mary Anne and Benjamin Disraeli, whose marriage seemed unlikely at the start but which grew into something not only strange but, even in modern terms, amazing. As she herself puts it in her preface:

The Disraelis’ story is about luck, and the path not taken, and transformative effects of a good match for a man and woman of modest means in nineteenth century Britain. It traces a journey from coldness to autumnal sunshine, and charts a marriage that wrote itself into happiness. It relates the history of people who remake themselves through their reading and writing, but also of people who disappear. And it is a story about what happens after the wedding, when the marriage plot is over.

They married in 1838 when Mary Anne was 46 and Benjamin (thereafter always called Dizzy by her) was 34. By then, of course, they both had back stories, and the first third of this book is a fascinating look at where they both came from and how their paths happened to converge. Dizzy’s story is better known, but the way Hay places it in the context of the times makes it seem fresh. However, it is Mary Anne’s tale that rivets the reader — a sailor’s daughter born in Devon, whose father died when she was two, who lived with her grandparents until her mother remarried when she was sixteen and who loved her younger brother, almost to the point of obsession, and was saddled with his profligate ways and inevitable debts all her life.

Like Mrs. Bennet in Pride and Prejudice, Mary Anne had high aspirations, and although she was never as poor as she liked to pretend in later life, she wanted desperately to be rich. So when Wyndham Lewis who was 14 years her senior came along in 1815, she saw her prize — a serious, honest (he didn’t cringe from telling Mary Anne that he had an illegitimate daughter whom he supported) Welshman who had ownership in an Iron Works and whose income was 11,000 pounds a year. Although that was more than Mr. Darcy’s 10,000 pound income, it was never enough for Mary Anne because Wyndham, though kind, was also stingy. So their marriage became a careful balance of maneuvering and deceit as she continually came to her brother John’s rescue and was attracted to other men (closer to her in age), yet somehow managed to become the wife that Lewis wanted.

For although Wyndham was smitten with her beauty and vivacity, he was determined to “mould” her into what he considered a virtuous woman. Not so easy, for she was street smart, headstrong, volatile, and quite capable, all her life, of saying things beyond the boundaries of Victoria etiquette, e.g. who was known to be good in bed, and dressing in a flamboyant manner that got only wilder as she got older. Still, by the time Wyndham became a Tory MP and she had begun to face the sad fact that she would probably be childless, they had moved to Grosvenor’s Gate, Park Lane in 1827, mingled with the upper classes like Rosina and Edward Bulwer Lytton, and settled into a life that seemed to suit them both.

By then Disraeli had survived a sickly childhood, been baptized when he was thirteen thus making it possible for his later career in Parliament (no Jews could stand for election until much later when Lionel de Rothschild, a friend of Disraeli, broke that barrier), graduated from Higham Hall when he was fifteen, changed his name from D’Israeli, and instead of going on to university (he was too young) had read around in his father’s library until he was twenty and decided to become writer.

His idol was Byron, but he saw himself as a novelist and published an autobiographical novel called Vivian Grey when he was twenty-six. Although it was dismissed in some quarters as trash and led to a breach with the influential publisher John Murray, who was offended by Disraeli’s portrayal of him, the volume was widely read, especially by women like Mary Ann who adored what were then called “silver fork” novels. A trip to Europe a la Byron in 1830 had opened his eyes and refreshed him and he came home and had an affair with a married older woman, and wrote The Young Duke and Henrietta Temple, which were received more warmly. By the early 1830s his strongest allegiances were to his father, Isaac, and his older sister Sarah, who had lost her fiancé to smallpox in 1831 and was now resigned to spinsterhood. It was she who knew most about his inability to manage money and who often tried to help him with his mounting debts, much as Mary Anne was helping John.

He and Mary Anne met by 1832 when Disraeli was entering the political arena and also socializing with some of the same posh Londoners as the Lewises. And by 1837 they had joined forces at Maidstone when Lewis invited Disraeli to run by his side as a Conservative candidate. Disraeli’s enthusiasm and Mary Ann’s know-how helped him overcome the anti-Semitism he encountered out on the hustings; when he won a seat in the House of Commons, she considered him her protegé.

Not long afterward, fate intervened. Lewis died suddenly of a massive heart attack at the age of sixty in 1838, and after much sparring back and forth — their “courtship” is both ridiculous and compelling in its swoops and swerves — Mary Anne and Dizzy married in August 1839, she taking on his debts, which were considerable, and living at Grosvenor’s Gate where, by the terms of Wyndham’s will, Mary Ann was allowed to live with all its servants and trappings until she died. At last, he was more financially secure than he had ever been, and she was married to an intellectual who could take her into the highest realms of power. Although they wrote flowery and sometimes cruelly honest letters before the marriage, neither seemed to see abiding love as part of their bargain.

Author Daisy Hay — she has done more in this biography than write about the Disraelis.

But the most interesting part of a human relationship is its ability to surprise, something that Hay understands all too well. Against all odds this marriage grew into something both substantial and admirable, with Mary Anne maturing in ways Dizzy had not imagined, becoming a wonderful hostess and gardener at their home in Hughenden, and “despite all her absurdities,” loved by both him and the public. Together they became close friends of Lionel and Charlotte de Rothschild, guests of Queen Victoria, and were welcomed at the most esteemed gatherings. (When Mary Anne was occasionally mocked, Dizzy refused to go back to those houses.)

As they settled into marriage Mary Anne was able to endure the roller-coaster of ups and downs that marked Dizzy’s career while he was in and out of Parliament, wrote novels and eventually became Prime Minister and one of the most famous and revered men in England. With her almost magical good nature she knew what he needed and even if she was not his intellectual equal, was loyal to him in every detail, even to dying his hair. Most important, she understood how complicated he was. Here is Hay on the task Dizzy had set himself regarding his heritage:

As he reinvented himself as an appropriate leader for his party, he still held fast to the myth of his Jewish heritage, the thing that made him different from other Tory MPs. He needed to be a man of property in order to conform to the model demanded by his party and so fulfil his political ambitions. But in order to conform to his own conception of the political leader, he needed too to be the descendant of an aristocracy of culture, faith and intellect older and more distinguished than that which ruled Britain.

So, together, Mary Anne and Dizzy triumphed and when he was offered a peerage, he asked that it be given instead to his beloved Mary Anne. And during her long illness with what is believed to have been uterine cancer, he grew more and more devoted. After her death at the end of 1872, Disraeli was never quite the same. Although he became Prime Minister again — this time with greater power and skill — and fell in love again, he knew that his marriage to Mary Anne was central to his success and happiness. And one can feel Hay’s joy as she ends their story — much as one feels a novelist’s joy when his/her story has a splendid ending.

But Hay has done more in this biography than write about the Disraelis. At the beginning of each chapter she has a short passage that tells a story about Victorian women, some of whom were known to Mary Anne and some simply picked randomly from letters or newspaper accounts. In them we learn about the loneliness and isolation of those women who were not able to find husbands and those who did but found themselves in unsatisfying marriages and those who had to content themselves with sex and attention outside marriage. Throughout her book she also reveals the isolation felt by Dizzy’s sister Sarah, by Rosina Bulwer Lytton, by other friends, by Mary Anne at times, and even Queen Victoria. By using these real stories as ballast, Hay immerses us in a time where women’s lot was constrained and often unhappy without resorting to sentimentality or pity. This is the way it was, she is telling us, and with these snippets Hay gives her book an uncommon texture and breadth.

I loved Mr. and Mrs. Disraeli, and hope that women’s book clubs across America find this intelligent, delicious tale, which can take its rightful place beside the novels of Austen and Eliot and Dickens and Trollope.

Roberta Silman is the author of a story collection, Blood Relations, now available as an ebook, three novels, Boundaries, The Dream Dredger, and Beginning the World Again, and a children’s book, Somebody Else’s Child. A recipient of Guggenheim and National Endowment for the Arts Fellowships, she has published reviews in The New York Times and The Boston Globe, and writes regularly for Arts Fuse. She can be reached at rsilman@verizon.net.

Tagged: A Strange Romance, Benjamin Disraeli, Daisy Hay, Mary Anne Disraeli, Mr. and Mrs. Disraeli